Q&A: 'WINNING TIME' Creator Max Borenstein Gets Personal about His Life and Work

The screenwriter behind GODZILLA, KONG: SKULL ISLAND, and the definitive Lakers TV series discusses his creative process and finding himself in his art

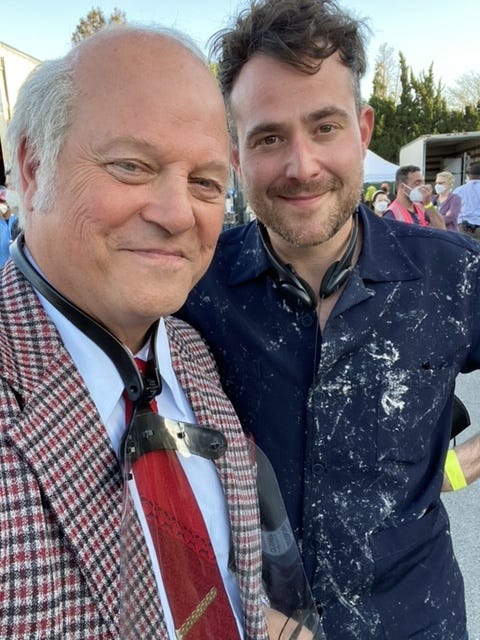

Max Borenstein and I met at a dinner part nearly a decade ago now, shortly before a little film he wrote called GODZILLA (2014)1 rampaged through movie theaters and grossed more than half-billion dollars worldwide. It was soon followed by KONG: SKULL ISLAND (2017)2 , which officially launched the so-called MonsterVerse that will return next year with GODZILLA X KONG: THE NEW EMPIRE (2024). But as envious as I am of my friend’s wild success at flattening cities on onscreen, it’s his less-destructive work that have most impressed me – especially, WORTH (2020), “THE TERROR: INFAMY” (aka “THE TERROR’s second season), and, most recently, the critically acclaimed “WINNING TIME: THE RISE OF THE LAKERS DYNASTY”.3 He agreed to let me interrogate him about his filmography, both to help me understand his process and find him in these disparate pieces of art. It turned into one of the most personal conversations I’ve had as part of this artist-on-artist interview series, culminating in a revelation that broke my heart for my friend. Read on, learn, grow.

COLE HADDON: Max, it’s been too long. I miss you, my friend. Tell me, are you writing at the moment?

MAX BORENSTEIN: Well, first of all — I miss you, too, dude. But I feel like I see you everywhere because your book [PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD] followed me to every bookstore that I’ve visited in the last four months. Every time I see it, I feel ridiculously proud of you.

CH: You’re too kind. I’ve felt the same here in Australia where “WINNING TIME” seemed to stalk me everywhere last year. You continue to blow me away.

MB: What am I writing? A few things. New things. Which is magnificent. For four years, I’ve written almost nothing but episodes of “WINNING TIME”. Now, while we complete post on Season 2, I’m writing two new movie scripts: one for me—based on a book I optioned, but very personal—and one for “them”, as they say. That one is a lot of fun, too. Can’t say much about either yet. But I’m excited, and having a blast with them both.

CH: If I look at the films and TV series you’ve written, I struggle to find obvious links between them – thematically, stylistically, subject-wise. I can make the leap from WORTH to “WINNING TIME”, for example, and maybe, maybe from the Godzilla/Kong films to “THE TERROR: INFAMY” – but I think it’s fair to say that your credits are a lot more diverse than Hollywood usually permits writers to be. We all live in boxes and can’t do anything other than what fits in them, or so we’re told. How do you describe what connects these projects for you – meaning, what makes them Max Borenstein projects?

The challenge becomes finding yourself in whatever happens to come along. Finding a way to fall in love. Not just get it up, but really fall in love.

MB: Man, that’s such a good question. The film you don’t mention in there is the feature I wrote and directed and edited and shot and acted in – along with a bunch of actually talented actors like Zoe Kazan – in college, SWORDSWALLOWERS AND THIN MEN. It was a completely personal film because it had to be. I had to be able to produce it for no budget in locations I occupied, with people I knew. So, it was very me.

Then I came to LA. I wrote a movie about my uncle, figuring I knew that, too, but his life was more interesting than mine was at that time. He was a criminal defense attorney dealing with death penalty cases. It felt personal, even though there was remove. It almost got made, [and] got me started anyway.

Point is: then I started getting hired. And when you get hired, and you’re a young up-and-comer, beggars can’t be choosy.

CH: Absolutely.

MB: The challenge becomes finding yourself in whatever happens to come along. Finding a way to fall in love. Not just get it up, but really fall in love.

It’s a project-by-project thing at that point. With GODZILLA, it was finding the thematic historical connections in the material, the visuals that tied to a post-9/11 kind of existential terror. For “THE TERROR”, it was using the horror genre in a similar way to expose this domestic political horror that had been largely forgotten in the flood of Greatest Generation narratives. In some way shape or form, all that was me, but it was really me finding myself in the material — interests, obsessions, iconoclastic impulses.

CH: And what about “WINNING TIME”?

MB: In many ways, it was a next step. I love basketball, and I grew up in the eighties in LA, so the themes and characters are very – much more explicitly – of my world. And because of the tonal freedom, I’ve been able to incorporate more facets of my personality. It can be dramatic, comedic, earnest, irreverent, all in quick succession. That’s why I think of it as my most personal project to date – which, for the record, can be a blessing and curse. It makes you care about every little thing a lot.

In any event, I’ve been rambling, but in answer to your question, as I look back retrospectively on the things I’ve made so far, I see facets of myself – my voice – unearthed like fossils in the material. In the early stuff, it requires one of those Jurassic Park X-ray machines to see the shape, then it’s dug up but covered in dirt, then that dirt is brushed away and – there I am, there’s my voice! That’s a weird metaphor. Know what I mean, though? Maybe you feel that way about your novel in relation to your scripts.

[Writers] go so long at the start of our careers with nothing coming in – just our hopes and aspirations boiling inside us – so once opportunity begins to knock, we answer, strip right down, and give it up before they even buy us dinner.

CH: I do, though my early screenwriting work is a lot more complicated to parallel because I think I got in the scripts’ way by making them too much me. You’ve obviously struck a much better balance, at least early on, between you and the needs of your producers and studios. As for PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD, it’s the most personal thing I’ve ever written, kind of the Kwisatz Haderach of everything I’ve ever learned about storytelling and loved about art, if you follow that reference. I wish I was closer to that kind of freedom on screen, but I’m glad your hard work has got you there.

Getting back to you, while it’s fair to say work can dry up in an instant in this business – risk never really goes away, I mean – you’ve nevertheless built up a deep, very impressive filmography at this point and there’s already much more to come. In a world where you now have a real ability to be picky – or at least pickier – about what you do with your time, how do you decide on which projects to pursue?

MB: Another great question. First, writer’s always have a Depression Era mindset. What I mean by that: you remember that generation, our grandparents or maybe great-grandparents, who grew up in the Great Depression so their whole life, even when they weren’t wanting or going hungry, they’d steal the little jelly packets from the diner just in case. Writers are that way with being offered projects. We go so long at the start of our careers with nothing coming in – just our hopes and aspirations boiling inside us – so once opportunity begins to knock, we answer, strip right down, and give it up before they even buy us dinner. Another bad metaphor, sorry, but you get it.

CH: Oh, I do.

MB: So yeah. I like to think that I’ve established enough of a reputation at this point, that if I can keep delivering some quality, I’ll have a chance to keep this going. And be picky – and I am. But it always takes an effort.

So, what do I pick? Like you pointed out, I’ve managed – somehow – to move eclectically through genres already. It was largely just chance, what came knocking, but it was largely indicative of my interests. And I always do my best work when I’m deeply engaged on various personal levels. These days, what I’m trying to do is be even more intentional about it. Resist that jelly packet urge to just say yes because the outside world – my colleagues or the town – would envy something. Try to do it only when it’s something that truly gets me fired up. That’s a new challenge. That’s why I’m writing something to direct again – for the first time since that film in college.

CH: I’ll resist the urge to ask more about that project…for now. As a showrunner – which has taken up a lot of your life the past several years – there are many in-person demands made of you, from the writers’ room to guiding the entire production. But is that your natural state as a storyteller?

MB: I love the process of being in production. It’s a thrill. But my “natural state?” It’s writing. It’s banging my head against the wall about a problem with a story, suddenly, eventually cracking said problem, and feeling that immense elation — that high. That’s my drug. And it has been for so long, it will always be my most natural state.

CH: Production is…well, chaotic. It’s wartime in Hollywood, right? Are you the kind of writer who could turn out an episode in a foxhole as bullets fly overhead, or do you prefer your office at home or a café with music in your ears?

My “natural state?”…[is] writing. It’s banging my head against the wall about a problem with a story, suddenly, eventually cracking said problem, and feeling that immense elation — that high. That’s my drug.

MB: Well, much like soldiers in the foxhole, you don’t really have an answer to that question until you find yourself in the shit. I’m sorry to say, I did find myself in the shit recently, writing desperately to deadline with production chugging right behind me in the tunnel like a freight train. And I’m proud to say that with the help of my collaborators, I got the writing done. I also got grayer in the temples, and may have disassociated. [Laughter] It ain’t fun, but it’s a high. Sometimes.

CH: In other words, it can be addicting.

MB: And it can produce great work. But the pressure is intense and when, God forbid, there are people in the process who are rowing in a different direction, be it due to creative differences or just their own anxieties – which all get amplified outrageously in those situations – things can get kind of traumatic. So yeah: turns out I can hack it.

But would I rather write with the comfort of a reasonable timeline, supported by creative partners who can manage their own egos and emotions under pressure? Yes. Always, and forever, and twice on Sundays. I’d also like to do it in Hawaii – which I have. All those Godzilla movies shot there.

CH: For the most part, film writing is a very solitary act outside of partnerships. Writers’ rooms are the opposite. Could you contrast the two and how the differences have forced you to evolve as a storyteller?

MB: I spent the first twenty years of my writing life – from age thirteen, when I started writing screenplays, badly, to thirtysomething when I had my first TV show – doing it alone. And as everyone who’s ever done it knows, there’s nothing more alone – and lonely – than writing. It can be beautiful and it can be hell. And you just have to keep on trucking through the good and bad times on your own.

After that, a writers’ room feels like a gift from the gods. But it comes with its own slew of challenges. I’ve now been working with rooms, on and off, for about a decade – so even though I think I’m starting to get the hang of it, I still have twice as much experience writing solo. In the end, I love a mix. It’s such a treat to have the genius of these other brains. But at the end of the day, I need that time alone at every stage – outline, script, revision – to do my thing. For me, that private time will likely always be my comfort zone.

CH: I’ve lost track of time and space, but sometime in the somewhat recent past I remember you sharing a photograph of the many books you were reading to research for “WINNING TIME”. Previously, you tackled “THE TERROR: INFAMY”, which involved one of the many, many horrific moments in US history, the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II; respecting that trauma was certainly important. And of course, there’s WORTH, which covers the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, which essentially determined what the lives of the victims of the terror attacks were “worth”. Can you talk about facts versus dramatic truth in your personal storytelling philosophy?

MB: Boy, that’s a tough one. Hemingway had a quote I’m going to butcher about writing being a pursuit of greater truth beyond the simple facts. So, yes, of course, especially in situations where you’re treating sensitive subject matter like 9/11 or internment, there is a huge responsibility to fact. But I don’t make documentaries. I’m not a historian. I’m a storyteller.

My goal in adapting a true story is to use that story as a vehicle for some hopefully resonant truth. To do so, you will always have to fudge things: consolidating characters, streamlining timelines, etcetera.

My goal in adapting a true story is to use that story as a vehicle for some hopefully resonant truth. To do so, you will always have to fudge things: consolidating characters, streamlining timelines, etcetera.

CH: Where’s the line beyond which you can’t tread?

MB: That’s always a subjective question. And the people the story is about will almost surely disagree with any choice you make. So ultimately it comes down to the gut instincts of the writer. As the judge said of pornography: you know it when you see it.

CH: Is there a difference for you in how important facts are when the real-life people being depicted are still alive if, at the end of the day, your fiction tells a truth facts couldn’t?

MB: The difference is those people are around to complain. They’re here to say, “That’s not how it really happened.” And sometimes they’re right – we made a choice for the convenience of the storytelling, in pursuit of that larger truth.

Sometimes, though, I have to say, they’re full of it. I’m not going to name names, but there have been moments when I’ve seen people complain about the details of a portrayal that comes directly from their own memoirs. I’ve seen other situations where people who lived through the thing together tell the story now in two completely different ways. This isn’t a surprise, of course. How many of us can recall what we did every day last week?

So, at the end of the day, all I can do is follow my heart and gut and ethics. I always choose characters whose lives and accomplishments I think merit a retelling – so I start from a place of immense respect. From there, I do my best and hope they like it. It’s very gratifying when they do.

CH: We’ve talked elsewhere about your obsession with cinema as a child. It was the same way for me, but, if I’m frank, not the case with every screenwriter I meet and, because of that, I’ve always had an easy time talking about the filmmaking with you. Common language, I guess you’d call it. Talk to me about yours. What form did it take?

MB: I was obsessed with musicals as a young kid. My parents introduced me. And I got to know every word of every musical – books and lyrics – to the point where I’d sing and dance and pretend to be Gene Kelly or whoever at family events. It was through musicals that I fell in love with other movies when I was, I don’t know, seven or eight. By the time I was twelve, thirteen, I was renting three to four videos an evening, then watching them as I dubbed copies on a pair of VCRs. This was the nineties.

CH: Oh, I remember this period well. When my dad died a few years ago and the kids had to sell his house, I found shelves and shelves of films I had dubbed that way. It broke my heart to have to throw them away.

MB: My dad just passed away, as well, and my mom is trying to clean house. One of these days, I know I need to rent a storage unit.

CH: Oh, Christ, Max, I didn’t know. I’m so sorry.

MB: So, I can’t help feeling sentimental – that was my film school.

CH: I can imagine.

MB: It was magical, and I saw everything a thirteen-year-old should never see — BARBARELLA, MIDNIGHT COWBOY, DEEP THROAT.

CH: Well, are you sure it was the “art of cinema” attracting you to those specific films?

MB: [Laughter] Good point. But honestly, at that age, prurience is one of the prime movers. I loved finding things that felt transgressive. It made the discovery so personal – my contemporaries might be watching “POWER RANGERS”, but I was so much cooler!

Meantime, I discovered this program, a CD-rom – this was before the internet – called Microsoft Cinemania. It was basically IMDB before IMDb, a hyperlinked movie encyclopedia. I’d follow the links from film to film, rent and watch those films, then spiral deeper and deeper. It was an incredible education. I never went to film school after that, and I don’t think I ever had to.

CH: How did your parents react to this hobby, this obsession of yours?

MB: My parents were incredibly supportive. They introduced me to old movies – the movies of their youth and young adulthood – and I always loved old things as a result. I was always more attracted to the films that came before me than the ones that came out when I was “of age” — with a few notable exceptions, like I saw THE BIG LEBOWSKI seven times in the theater. My parents and I saw it, and loved it so much we snuck back in and saw it again. That’s before it was a cult hit, mind you. Back then, I think we were the cult.

The greats steal, too. All the time. They just call it inspiration. And it makes the world turn.

CH: That kind of deep education in cinema provides a screenwriter – authors, too – an incredibly varied toolbox with which to tell their stories. Can you provide any examples of how it impacted films or TV you’ve written?

MB: Oh man, it’s true in countless ways and constantly – I steal all the time! The truth is it actually feels more like stealing than it ever turns out to really be. You go, “Okay, I’m writing a heist thing, how’d [Sam] Peckinpah pull it off in WILD BUNCH?” You start stealing freely, but you can’t stop your brain inventing, so by the time it comes out on the other side it has a freshness and originality. For better or worse, it stops being Peckinpah – starts being yours. For GODZILLA, we ripped off CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND shamelessly. Then eventually – director Gareth Edwards and I – we both independently met Steven Spielberg, and he said how much he liked the film. If he knew we ripped him off, he had the grace to keep that to himself.

But the greats steal, too. All the time. They just call it inspiration. And it makes the world turn.

CH: Final question. I love that incredibly nostalgic – but lovely – description of you and your parents being a film cult “back then”. Did your father have, or do your parents have – tenses are never fun when talking about those we’ve lost – but did/do they have any opinions about what your best work is so far and do you ever consider them in the audience when thinking about story?

MB: Well, you know, they’re my parents. They love seeing my name on anything. But I will admit, there was one movie I took my mom to the premiere – my dad was pretty sick by then –and it was not the finest film I’ve had my name on. I thought it stunk. And walking out, there was this long moment of polite silence, then I said “Man, that sucked.” And my mom just exhaled relief, “Oh thank God you thought so, too!” Because she’s loyal, you know. So, she’d have taken that one to the grave.

CH: I love that story.

MB: But that’s one thing that’s really special about “WINNING TIME”. I love it, they love it, I’m proud of it, and I don’t feel like it requires any caveats or apologies. So, I’m really glad I got to watch that one with them before my dad was gone.

But wow…do I ever consider our little “cult” when thinking about story? Yeah, now that you mention it, I think about it all the time. Movies were this glue between us, this lingua franca we had – a shorthand through which we could communicate for our entire life together. What a blessing to be able to contribute to that lexicon of cultural language going forward. I sure hope there’s some young kid out there, watching my shit with his parents, captivated, experiencing this brand new thing together – and using that spark to ignite a lifelong love of film.

You can find Max Borenstein on Twitter. His film HYPNOTIC, which he co-wrote with Robert Rodriguez and stars Ben Affleck, hits screens this week. Season 2 of “WINNING TIME” arrives in August.

If this article added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is now available from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Paperback will hit shelves on May 25th. You can order it here no matter where you are in the world:

GODZILLA was written by Max Borenstein, story by David Callaham

KONG: SKULL ISLAND was written by Max Borenstein, Dan Gilroy, and Derek Connolly

“WINNING TIME: THE RISE OF THE LAKERS” was created by Max Borenstein and Jim Hecht