Q&A: Journalist-Turned-Screenwriter Michael Bronner Is a Big Fan of the Truth

'The Mauritanian' and 'Rogue Agent' scribe on the differences between journalistic truth and dramatic truth - and the critical role of both in changing the world

Michael Bronner lives at the intersection of journalism and filmmaking, a point of tension between factual reportage and dramatic storytelling. Once an investigative journalist - the kind I wish I’d had the courage to become - his skills eventually made him indispensable to director Paul Greengrass, who asked him to help bring the 9/11 story of doomed United Flight 93 and its brave crew and passengers to the big screen. After United 93 was released in 2006 to critical acclaim, their working relationship continued through Greengrass’s next two films, Green Zone (2010) and Captain Phillips (2013); Michael received producing credits on all of these. But by this point in his cinematic side-hustle, Michael’s passion for finding the dramatic truth in stories - not just the factual - had him by the throat, you might say. There was no going back for him, as evidenced by the artist-on-artist conversation I’m about to share with you.

As a screenwriter, Michael now calls upon his journalistic skill set to excavate secrets and gain access to sources other writers wouldn’t be able to. But in doing so, he must wrestle with how to dramatize those facts in a way that doesn’t undermine them.

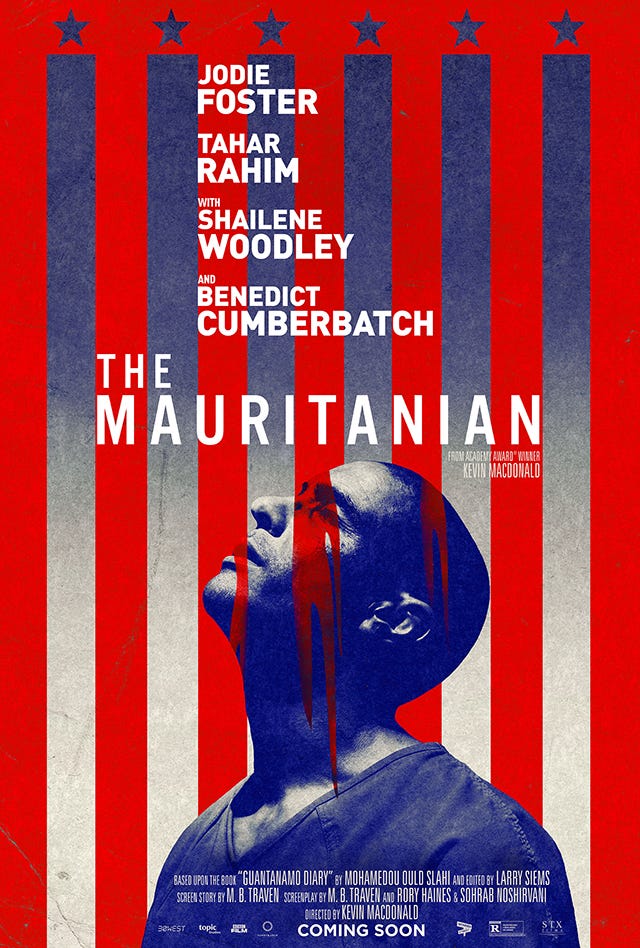

His first produced credit was for The Mauritanian (2021), adapted from Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s non-fiction book Guantánamo Diary about his fourteen-year-long incarceration at Guantanamo Bay detention camp.1 His next film was released in 2022, Rogue Agent, which was based on his unpublished article “Chasing Agent Freegard”.2

What you’re about to read is one of the more profound conversations I’ve had about art and storytelling here at 5AM StoryTalk. The reason for this is that every single word of what Michael and I discuss concerns the imperiled role of facts and truth in our culture and the power of both journalism and fiction to inform and shape our understanding of the world — and very often change it.

COLE HADDON: Michael, this arts newsletter is an expression of me and, as such, it’s as endlessly interested in the intersection between mediums as I am. For the sake of this conversation, let’s call journalism an artistic medium, too, if only because it can and often does blur lines to tell compelling and exciting stories. As someone who has now worked extensively in both, I was hoping you could discuss what you believe are similarities between the craft that goes into each.

MICHAEL BRONNER: First of all, thank you for tapping me to be part of this dialogue. Writing involves such long stretches of isolation – hopefully punctuated at intervals by getting to actually make something in the company of great colleagues – but it's invigorating generally to converse with fellow writers in a deeper way about how we've chosen to spend our lives.

Your question is about the overlap between journalism and scripted writing for film or TV, but the blur of mediums in my career is a bit wider. I spent my university days writing poetry and short fiction in a creative writing program, mentored by stalwart surrealist Sidney Goldfarb, who insisted at once upon discipline and departure in our writing, all of which would prove integral in journalism as I hit the road.

CH: How so?

MB: Discipline in terms of being present and aware – to be constantly interrogating what you’re experiencing, looking for the essence beneath the surface – and always with an ear for language and the intention of someday writing it. Departure in terms of letting go of all that keeps you from being present – and in terms of hitting the road. I came across one of my favorite quotes from these days, from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time – “To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.”

Whether it's fiction or long-form investigative print journalism, long-form broadcast news, or writing a screenplay for a feature or a television episode, it's all storytelling in the end – deploying language to conjure life – even if each form may have its own rules. I would say writing poetry prepared me for narrative journalism – though it killed any interest in basic newspaper writing, which is too straight and formulaic. Writing scripts for twelve-minute “60 Minutes” pieces – after doing the research, interviewing your subjects, producing and directing the shoots – is all relevant for a further departure into writing and producing features. Deep research has always been the bedrock – where I always start, no matter what the medium – and building a degree of expertise and understanding of a subject or “world” for me is a prerequisite for having enough confidence to begin to write.

When I first started writing screenplays, necessarily on spec, I would often pitch a magazine piece to a familiar editor and do a journalistic version first as a way of funding the time, travel, and research required to write the screenplay.

CH: I’ve done similar in the past, but could you explain what that means to my readers?

MB: For example, I wanted to write a movie about a whistleblower in the Swiss banking world – a guy who was criminally implicated and came clean, going to the FBI and doing serious damage to his former employer, over the course of which he had a reckoning with himself, his family history, his ambition. But I knew next to nothing about how the Swiss banking world actually works, and I needed to, lest it end up generic uninformed bad-screenwriter nonsense. So, I'd end up doing the reporting first, with all the specific rigor that requires, commissioned to publish a magazine series first. The access was invaluable. I spent several hours with the real guy – the whistleblower – the evening before he had to report to prison. I overheard him speak with his father. Later, I did a follow-up interview in the prison and got tossed in a cell myself after breaking the rules by taking a snapshot of the prison expanse in the snow - an arty little image on the way out, I thought, but the warden didn't agree.

CH: Jesus.

MB: I really do hate entering prisons, something you sometimes have to do as a journalist. Being forced to reenter one by angry gun-toting guards in order to be hauled to the warden’s office is worse. “You’re lucky you didn’t get shot,” one said.

Writing the magazine piece gave me the opportunity to work out some of the structural approach to the storytelling that I'd use later in the screenplay. Once the magazine piece ran, it was really a pleasure to then shake off the rules of journalism and fictionalize, sticking close to the turns of the real story, writing a story deeply infused with journalism, but freed to explore its dramatic depths in fiction. That script, one of my first, almost got made a handful of times. I called it The Banker. It's dated now, but maybe I'll go back to it sometime, keep the characters and turn it into something else – another freedom of screenwriting versus journalism.

CH: Good ideas never die. I’m curious how you view United 93 in the context of your experiences as a journalist and filmmaker – a storyteller working at the intersection of the two

MB: United 93 is probably the best example of a whirlwind of overlapping forms working together. It was a piece of journalism – "The Recruiters' War”, which I wrote for Vanity Fair – that got the attention of Lloyd Levin, United 93's producer, and Paul Greengrass, our director, both of whom became great mentors and friends. Paul wanted to make a film about 9/11, and all of my journalism at home and abroad had essentially been related to 9/11 over the four years since the attack, and we started talking. At some point, after several late-night, hours-long phone conversations, he said, “Well, does it make sense for you to come over here and we try to make something?” What followed was an exhilarating crash course in Paul's unique, natural style of deriving drama from journalism, which felt completely organic to me with this project. Paul, if you didn’t know, also transitioned to feature film from broadcast journalism (Grenada TV’s “World in Action”).

CH: I’d forgotten that detail about his backstory.

MB: It’s a critical thread throughout his work, even the Bourne movies. United 93 was a movie, but given the sanctity of the material, it was one that absolutely required journalistic rigor. None of us felt we could ask an audience to take that painful leap with us back to 9/11 unless there was something real to learn and discover, both about the facts and the drama of that day. We had to learn how the civilian air traffic system worked, and the unique language spoken by the air traffic controllers. The same was true for the military air traffic system, which was very different. The dissonance between the two caused a lot of problems during the attempt to respond to the attack, as the military and civilian radars didn’t work the same way.

As a journalist, I knew how to get the real people involved to talk to us and share their experiences in fairly granular detail. I made several trips to NORAD's Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) in Upstate New York, which was the Air Force facility controlling the fighter jets on 9/11. We even had a senior member of the 9/11 Commission with us on set. It was a 90-minute movie about a 90-minute attack, so a very direct level of precision was possible.

CH: All that precision shows up on-screen, too. It’s very easy to forget you’re watching a film while actually watching the film, something I’ve rarely experienced. I’ve seen United 93 five times now, I think, and the experience is always akin to slipping through time. I’m not sure if you’re a comic book fan, but there’s a strange sense of the character of the Specter about the direction – hovering at moments of tragedy, present but forced to be nothing more than a witness. Without the details you describe, I couldn’t say any of that.

MB: The cinematographer on United 93 was Barry Ackroyd, who’s not only immensely talented but has extensive experience in documentary photography – that’s where much of that feeling of being present comes from. He’s been a close collaborator of Paul’s on several films. We would set up an environment – the national FAA Air Traffic Control System Command Center, for example – and there would be a dozen or more air traffic control professionals playing the roles alongside one or two professional actors, and they’d be surfing the real incoming air traffic data from 9/11 - which we obtained - on replicas of their actual consoles. The takes would run ten minutes, sometimes double that, and Barry and camera operator Klemens Becker would move through the scene shooting, as if exploring an unfolding event in real-time. They were shooting film, so they’d stagger their starts so that one could reload while the other was still shooting as the scene continued to unfold. I was behind the monitors with a handful of phones in front of me and a stopwatch, and I’d place calls into the scene – into the “air traffic control room” during the take – with the real inputs to time: “Command Center, Washington Center, we have another one – American 77…” And the actors/controllers in the scene would react – “We’ve got another one!” It was tense and crazy, key to the way Paul creates physical and emotional tension. I learned an incredible amount.

CH: I can only imagine. It sounds like an intense, but life-changing experience.

MB: We broke news in the film, too – not a usual function of Universal Pictures. After learning that there were audio recording machines spinning at NEADS throughout the attack, I made an impassioned case to NEADS military brass to let us hear them. They didn’t say “yes,” but they didn’t say “no.” During the last days of the edit on the film, a CD arrived anonymously in the mail. It had a blue sky decal on it and contained thirty hours – six concurrent tracks – of the raw recordings of the military air traffic controllers struggling to get a grip on what was happening, hurling mostly unarmed fighter jets at ghost tracks of civilian airliners that had already crashed – three out of four into their targets. They were electric to listen to. There were only four armed fighter jets on call on the East Coast on 9/11, so they were launching unarmed jets with the plan to ram hijacked commercial airliners in suicide missions for the pilots if they could find any – and you could feel that grim resolution on the tapes – but of course it never came to that. By the time they got the fighters up, the hijacked planes were all already down.

CH: I’ve never heard this detail. What an extraordinary gift for storytellers hellbent on authenticity.

MB: The truth about 9/11, proved by the time-stamped recordings, is that there was no real-time military response to any individual hijack. By the time word of each of the four hijacks traveled from civilian air traffic control to the military, it was too late – the plane had already hit its target or, in the case of United 93, crashed in a field. They struggled to hurl fighter jets in the directions of where they thought the planes were – following ghost radar trajectories – but it was futile. The time lag in reporting and response got worse over the day, not better – it’s all on tape! We embedded the recordings deep in the soundtrack of the film, but the tapes were important beyond the movie, obviously, so after the Tribeca premiere, I switched hats back to journalism again and wrote a magazine piece - "9/11 Live; the NORAD Tapes" for Vanity Fair.

But not all movies require the strict journalistic rigor that United 93 did – most don't – and I would come to realize I still had a lot to learn about the differences between the two mediums in order to find a real point of departure as a screenwriter.

CH: We’re going to come back to this point of departure for you as a screenwriter in a moment, but I want to discuss your experiences and perspective as a journalist a bit more first. The concept of truth seems to be under attack in unprecedented ways thanks to the ascendence of social media and the breakdown of various social compacts regarding the media and even politics. I’m curious what you see as the limitations of journalism as a delivery mechanism for “truth” – whatever that means to you – in the 21st century?

MB: This question feels like one that defines our times. It's one I think about in work and life every day. The incredible outpouring of phenomenal journalism during the Trump presidency, particularly investigative journalism, corresponded for me, conversely, with a personal despondency around journalism. So much of it – no matter how revelatory – just hasn't seemed to matter. This has continued into the Biden Administration. It was once the case that the Democrats were somewhat more reactive to exposure and embarrassment – I’m not sure anymore. Look at the Supreme Court. Is there a question that Justices Thomas and Alito should have recused themselves from the Trump immunity case? They stayed on to upend the country’s democracy, with help from the other so-called “conservative” justices - who aren’t conserving anything, but rather pushing the nation into unchartered waters. There’s been great reporting exposing them, but it doesn’t move the dial. It's cliché to say that people today look for the kind of news – or "truth" – that reinforces their worldview while rejecting the rest, but it's a real dynamic. The storytelling of journalism can still work its way emotionally to the heart of a reader or viewer – and that's the hope, still – but facts on their own, however brazen, seem to move people less.

All of the above applies to good journalism—

CH: Of course.

MB: A more deeply depressing dynamic is the overwhelming slew of ideologically driven, disingenuous, wittingly distorted bad journalism purveyed today. I'm not talking about lone wolves on social media, but mainstream news organizations. The Gaza nightmare has been case in point. I've reported from Israel and Palestine over the years, beginning in 1998, and I've never seen the realities of the conflict so adamantly and relentlessly distorted as they are now, day in and day out – a willful dehumanization of Palestinians – a dynamic made possible by racism. Sixteen thousand kids killed? It's taken me to a really dark place, if I'm honest. I canceled my New York Times subscription after three decades.

CH: Same here.

MB: The gaslighting feels overwhelming. Just on a professional level, there have been more than 130 Palestinian journalists killed – professionals, real reporters, colleagues. The Committee to Protect Journalists, the U.N., Human Rights Watch and others have accused Israel of deliberately targeting journalists, and it’s barely mentioned by the mainstream press, let alone with the outrage it deserves.

Note to readers: The U.N. and Committee to Protect Journalists place the current number of journalists killed at a more conservative 131 and the Gaza Health Ministry at 183.3

MB (cont’d): Journalism is a business, and it's always been a fight to get certain stories on the air. But I find the decline in integrity around certain stories – sometimes the most important stories – much more offensive than the chaos that reigns on social media. The New York Times and the main broadcast networks are vastly better resourced than freelancers, who work at much greater risk, or so-called alternative news organizations, many of which do really great work – and these big media "of record" too often squander that privilege and responsibility.

There are some gems on social media – people in the midst of stories they know as well as they know themselves – that relay real truth in a more raw, informal, untrained sort of way that's invaluable. There is a young Palestinian woman, Bisan Atef Owda, who has been filing riveting daily video blogs from Gaza providing first-hand insights into life in the Strip under fire since Oct. 7th, which AJ+ wove into a documentary, It’s Bisan from Gaza and I’m Still Alive. The second title echoes the words with which she begins each dispatch.

CH: Yes, I’m very familiar with her courageous work. Why don’t you tell my readers a bit more about her, from your perspective, in case they don’t?

MB: Bisan and AJ+ won a Peabody Award for the doc – but when the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) nominated Bisan and AJ+ for a News & Documentary Emmy, some 150 Hollywood actors, agents, and executives signed a letter condemning the nomination, calling her a terrorist and demanding that NATAS rescind the nom. Are we going back to blacklisting?

Bisan is a refugee displaced within Gaza maybe two dozen times, filing her reports in one of two or three shirts she carries, whose opening line – “I’m still alive” – could be voided in any instant. As a Peabody Award winner myself, and a three-time Emmy nominee in the News & Doc category – and as a Jewish guy whose grandparents escaped Germany another time a powerful army was wiping out whole families – I found the intervention to try to squelch her voice vile. Kudos to NATAS for rebuffing the attack4 and refusing to rescind the nomination. She went on to win the Emmy. Recently, a group of some seventy Palestinian filmmakers including two-time Oscar nominee Hany Abu Assad, acclaimed director Elia Suleiman and BAFTA winner Farah Nabulsi have now signed a letter calling the industry out5 more broadly. These, again, are our colleagues.

One has to press on and support each others’ work and take faith that moving people still matters.

CH: Let’s get into the point of departure from journalism that explains your interest in – maybe even passion for – drama.

MB: Definitely passion.

CH: How do fiction and film/TV – really, the arts in general – compare as a way to explore “truth” in your mind?