Q&A: Journalist Maureen Ryan Wants to Burn Hollywood Down

The 'Burn It Down' author discusses Hollywood's history of abuse, why she's determined to see the culture change, and our complicated relationship with problematic art and artists

If you’re a regular reader of 5AM StoryTalk, you probably know I have lived through some pretty traumatic experiences during my time in Hollywood. That’s probably why I’ve valued arts journalist Maureen Ryan’s deep investigations of similar abuses and many, many, many others that make what happened to me seem like amateur hour by comparison. Her daring work has given voice to countless victims of psychological abuse, racism, sexism, and much more - including sexual harassment and assault. It’s helped change how writers’ rooms work, in particular. Without question, she has made the American film/TV industry a safer place.

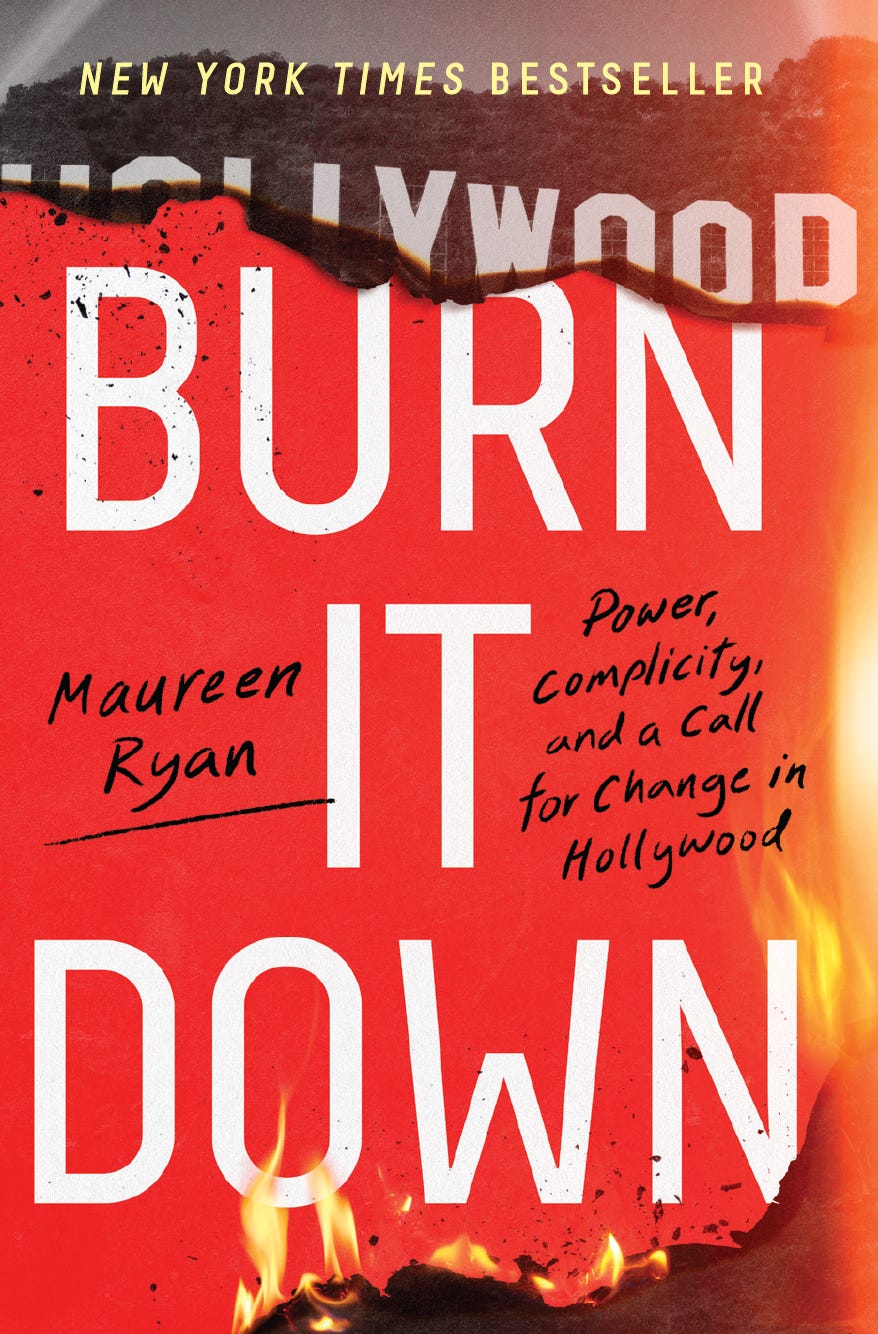

Last year, what will likely be Maureen’s — or Mo’s — magnum opus on this subject was published. Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood is a harrowing read, to say the least. It dredged up so many memories for me that I still found it difficult to get through when I reread it earlier this year in preparation for my conversation with her. But what makes Mo’s incredibly detailed and damning indictment of Hollywood — its culture of abuse, its moral hypocrisies, its idolization of and commitment to protecting people (typically, men) who should otherwise be unemployed and even in prison — so powerful is that it’s predicated on her passion for film and television and solutions to change the system.

Obviously, I’m a big fan of this human being.

That’s why I was stunned to discover Mo is a diehard reader of 5AM StoryTalk. She popped up as a subscriber a while back, and I couldn’t stop myself from emailing her to both thank her for her work and ask her if she might join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations. While Mo herself wasn’t necessarily an artist, she had committed her life to the arts and serving them in a way I admire and find incredibly important. Plus, given the subject of her Burn It Down and her other journalism over the past several years, I thought she was the perfect person to discuss the subject of problematic art and artists. I asked her in that first email, how do we distinguish between artists, art cultures, and the art they produce? Should art be judged based on the artist's personal life? How do we enjoy art we know is predicated on pain and abuse and violence?

Mo’s thoughts on these questions and many others are profound, to say the least. I expect they will challenge some of you; for others, they will articulate something you maybe haven’t found your own way to express yet. Along the way, she and I are going to dig into her love affair with film and television and what she thinks makes a great TV series, but also — obviously — Burn It Down. Specifically, her own challenges bearing witness to so much trauma and the incredibly compassionate reasons why she wrote it. When you’re done reading this chat, please consider ordering a copy of the book for yourself - which just came out in paperback. I think it’s an essential read if you care at all about film/TV.

COLE HADDON: Mo, we’re going to get into some heavy questions, I expect. So, I wanted to start with something…well, the opposite. Let’s talk about passion and, specifically, where yours for television began.

MAUREEN RYAN: There are so many moments that made this career path kind of inevitable, though it often didn’t seem that way. But I’m going to reframe your question a little bit because I think in doing so, it’ll give folks more of a big-picture idea where a certain strong thread of my criticism and industry coverage comes from.

CH: Please do.

MR: A huge part of my whole deal is love and profound gratitude for excellent storytelling — in all creative spheres — that transports me into other worlds. There are exceptions to this, of course, but the works I love the most tend to provide a portal out of this existence and into an intriguing world I never would have been able to conjure on my own. They provide me with people and relationships and ideas that help me process and consider my own existence - and realize that other kinds of existences, futures, and paths are possible.

Though what I’ve just said makes it sound like I’m a huge sci-fi fan — and I totally am — this “other place” can be a hospital, a corner of hell or heaven, an office, a post-apocalyptic future, a place with dragons, a fast-food workplace, a hotel or a hallway, whatever. I just like to feel unconsciously immersed, you know? I mean, not truly unconsciously. I’m thinking and feeling, but in a sense, I forget my existence in order to see the world through these people’s eyes. As long as I feel enveloped by the people, by their evolving relationships, by their moral and personal dilemmas, and as long as I’m intrigued by what is happening and what could happen next, more often than not, I’m all in.

CH: Absolutely. Environments — even genres — are just vehicles with which to explore the human experience. Or at least that’s what they are when done right.

MR: Exactly. When I’m speaking to aspiring industry folks, I use this rubric when I get into the nuts and bolts of storytelling. Of course, it can never fully be summed up — a universal working model of effective storytelling, that is — but this two-part sentence fragment distills a lot of it for me: “What happens next…to these people?” When I care about both of those things, when I’m fully invested in both halves of that phrase, we are really cooking with gas.

Since childhood, I’ve loved falling into worlds that other people — or another person — created. To be fully wrapped up in an atmosphere, in relationships, in unsolvable problems and kickass solutions, in characters, in places - that’s the stuff. And I don’t have to fully understand all of it to enjoy the piece. In fact, quite the opposite!

CH: Can you give me any examples?

MR: I go on a lot about the French TV series “Les Revenants”, which I still think about all the time, in part because I love it deeply, but I did not fully understand what was going on a fair bit of the time. But the story elements that were clear, the themes about grief and loss and how life is an overwhelming mystery at times - those drew me in like few shows ever have.

Side rant: If you think I’m saying “Les Revenants” is just fully gauzy and not well-crafted, I’m not saying that at all. The first ten minutes of this show are more gripping than some programs are across multiple seasons. The premise is very smart and rock solid. If you aspire to make TV and you want to make a TV show that runs on vibes only, more or less, like “Les Revenants” often did, please understand that those vibes have to be truly exceptional. Your show has to be on the Mount Olympus of vibes-based entertainment, and I’m going to be real with you - most people can’t get there.

CH: I don’t disagree with you.

MR: I’m glad I’m not alone! Yeah, it’s very, very hard to make a show that has an atmosphere or aesthetic so compelling that the plot can be pretty wispy. Over the years, I’ve seen a lot of shows in the drama realm try to coast on those elements, but unless you’re operating on the level of “Twin Peaks” or “Les Revenants” — and almost no shows are, ever — you need more than that. You need a fucking story, too.

CH: I’m so glad you brought up “Twin Peaks”, which had such a profound impact on me as a storyteller. Well, most of David Lynch’s work has.

MR: I’ll share one of my favorite memories of all time. I can remember exactly how the early evening light was falling in my little one-bedroom apartment on Buckingham Street in Chicago when the pilot for “Twin Peaks” began on ABC. I did not understand it — not fully — I still don’t! Thank the gods.

Of course, there was the murder mystery that drove much of the storytelling early in the show, but there was so much else going on in “Twin Peaks”. To this day, could I define what those “something elses” were? Not fully. As is the case with probably my favorite album of all time, Kate Bush’s The Hounds of Love, “Twin Peaks” was filled with the kind of mystery and possibility that resist final and definitive analysis. “Twin Peaks” offered a series of deft, brilliant moves — visually, narratively, lyrically — that pulled me in and has not yet let go. And it was so often funny and subversive.

CH: It absolutely was.

MR: I love the validation. And because sometimes I yell, I’m going to yell it again – quite often the best art in the whole world is funny and/or not heavy all the time. Human beings aren’t in one narrow mode all the time. You don’t have to be grimdark or relentlessly bleak to create “Serious Art”. That last sentence may be my next tattoo.

We’re going to talk about some terrible shit in this conversation — that is, in part, my brand — so I need to balance the scales with some great moments. When I did a cover story for Variety on “Twin Peaks”, I got to talk to Kyle McLachlan, Laura Dern, Mark Frost, executives who worked on various versions of the show, and of course, David Lynch. For the most joyous reasons possible, I can’t fully describe what that was like either. I’ll just give you one little glimpse. When the drama was revived on Showtime, the publicity team had Lynch in a suite at the Chateau Marmont, and I met him there to do the first interview for my story. So, I turn up, nervous as hell, very excited, and David Lynch comes in and part of me is fully freaking out, but I keep it together. And immediately, he put me at ease somewhat by saying, in his very distinctive David Lynch voice — nasal like my Midwestern accent — “Mo, tell me about your tattoos.”

And so, I sat on a couch at Chateau Marmont and talked to David Lynch about my extensive ink, and if he was not genuinely interested, he did a good job of faking it — but I think he was actually interested. Many real titans of art, I find, are endlessly curious. That is a big part of the job description.

CH: Lynch’s work has had such an influence on me and how I create, as I mentioned. Other people probably wouldn’t see it — mostly because I think most people don’t truly understand what he does — but his influence can be found throughout my debut novel. There are few artists I’d love to get in a room with more than Lynch, just to talk art, creativity, life in general. Bit of a dream, really.

MR: It absolutely was a dream. He’s an interesting interview. Nobody makes more left turns when you speak to him than Lynch, and you’d better be able to keep up. It’s like the Formula 1 of interview situations - if you’re prepped and ready and willing to go for it, it’s a little scary but mostly incredible. He’s a very smart man, and I think he — like a lot of artists — likes being both sincere and keeping people a little bit off balance. Not in a bad or mean way, but he’s interested in keeping himself interested – and there’s always that curiosity at work. I’ve seen him wrap entire press conferences around his little finger doing his whole David Lynch thing — and nobody can predict what he’ll say next — and it’s entertaining as hell.

Anyway, as great as the day with him was, I went to the photo studio in L.A. where the cover shoot happened, and that was even better. Without question, it was one of the best days of my professional life. They brought in a vintage car — I saw them drive it into the studio! — and had Bob Dylan playing over the speakers. I watched Lynch, Dern, and Kyle MacLachlan goof around and talk and have a good time — I hope — while posing for photos. In between all that, I did more interviews. If there is a better situation for an arts critic than watching David Lynch and Laura Dern joyfully have their photos taken while that critic is talking to Kyle MacLachlan about Special Agent Dale Cooper, I genuinely do not know what it is. I’m sure you can relate to this - sometimes the joys of what we do are wildly beyond description.

CH: Oh, trust me, I can. My stories are more from my life as a filmmaker and novelist, but I remember experiences from my time as an arts journalist that were life-changing.

MR: By the way, not every show has to be or do a “Twin Peaks”-esque thing – be a mystical experience I can’t describe or something that changes the path of my life. But I just love being fully involved, completely drawn in by what I’m watching. When I first watched Star Wars in a theater when I was twelve, when I first watched “House’s” “Three Stories”, “Enlightened’s” “The Ghost Is Seen”, “Supernatural’s” “The French Mistake”, or the revived “One Day at a Time’s” “Not Yet” - my brain and my soul and my gut were all fully engaged. And to this day, with a great film or episode of television, my opinions or theories about it change all the time. A lot of my online work — on social media or via blogging or newsletters — consists of me saying, “I have some thoughts about this…what do you think?” Back in the day, being able to write weekly about shows like “Mad Men” or “Breaking Bad” was such a gift. I wanted to figure it out along with everyone else, my fellow critics, my fellow audience members, my fellow story-lovers. And that’s why coming up when I did — when so many other writers and viewers and creators could be part of this big conversation — has been such a rewarding experience.

CH: I have a very visceral reaction to what you’re saying here, and not in a positive way. Not to make this about me, but more and more, I find myself abandoning TV. There’s just too much of it. I feel assaulted, quite frankly, by how much is out there. And whatever I do watch, I will very rarely have many people to share the experience with. I miss being part of a “big conversation” — that sense of community around something I love — that has largely disintegrated thanks to streaming and so-called Peak Television.

MR: Oh God, I feel seen! Yeah. I mean, I love TV, and I’ve devoted much of my adult life to writing about it in various ways. And I’m sure a lot of your readers will agree with a lot of the following proposition: The downsides of Peak TV are tied to the downsides of the industry’s current financial models.

Look, we both know the problematic elements of the TV industry of the ’80s, ’90s, Aughts, and beyond. But as a business proposition, it worked. It made many people and companies a lot of cash. But right now, so many industries are being, in an apt phrase I recently came across, “looted into failure.” It’s all being Zaslaved to death – so many hardworking artists and crew are unable to make rent or pay bills, while the people on top make tens of millions or billions. Obviously, I don’t need to explain the last decade to those in the trenches. But ultimately, the goal became not, “Let’s try to create stories that connect with the public and/or advertisers so we all make money” – it became, “Let’s try to make a lot of product and shove as much as possible out the door while looting the joint.” Not great, Bob!

MR (cont’d): Anyway, this clearly had an effect on my work-life balance, as it kind of destroyed the tiny scrap of it that I’d clung to. I had quit my job at Variety in 2018. I did that for a lot of reasons, but one of them was my brain has only so much thinking and considering capacity. What you want from a critic is the sense that they thought about the work they encountered. Even if you disagree with me — and you can! — the whole goal was to get to this place: “I have considered this, I am able to place it within the overall context of the television industry, and I can tell you what kind of itch it will scratch, and if I think the goals set out here were met – and if they were worthy goals in the first place.” But it all became too much, just the sheer amount of TV coming at us. I didn’t want to do a full-time job where I felt I could not routinely do justice to something people had worked hard on. I still do write reviews. I loved-loved-loved reviewing Everything Everywhere All at Once for Vanity Fair. But after a couple decades of riding that wave to the peak and beyond, I just wanted to peace out while I still felt the love for the medium of reviews.

But another reason I left a high-profile staff job was because I wanted to do more in-depth reporting on the industry – and I wanted to do it in an artisanal fashion, if you will.

CH: What does that mean to you?

MR: I work in a very, very specific way, one that is deeply informed by my attempts to not further bully or traumatize survivors of all kinds of misconduct. You need time for that. A whole lot of time.

And by the way, on that topic, I want to give a shoutout to my peers here – not just at Variety, but across a whole range of publications. A lot of us who already had demanding and time-consuming jobs looked at the industry after MeToo broke open, and we took on hugely difficult second jobs that entailed doing necessary and very onerous reporting about misconduct and toxic systems within the industry. We were already busy, but we committed to that hard path. That said, over the years, between Peak TV and MeToo and all that, my workload kind of doubled and then doubled again. For a long time there, I was also taking care of two sick parents, raising a kid, and trying to stay married to a very good person. It was…a lot. When I look back at the last decade, I see that it’s possible that I may have a wee problem with workaholism - but that’s probably a conversation for me and my therapist.

CH: [Laughter] I empathize, trust me. So, as we talk, it’s been almost a year since Burn It Down was published. I recently emailed you about how hard I was finding it just to reread it, and I’m not the person who had to sit through these interviews and spend so much of my emotional energy making sense of so much vileness. How is your recovery going, if “recovery” is the right word? After all, it didn’t just end for you last June when it hits bookshelves. You’ve had to spend a year promoting it, talking about it, reliving it for better or worse. And now, you’re about to do it all over again for the paperback release.