'Armageddon': The Most American Film Ever Made From the Most American Director Ever?

Let's consider what this disaster flick has to say about U.S. culture and the rise of Trump's MAGA movement

Some films should not work, and yet the sum of their messy, even inexplicable parts amounts to something…well, spectacular. Armageddon (1998) is one of the greatest examples of this cinematic phenomenon. But as impressive as this feat is, a kind of magic trick only director Michael Bay could pull off, I think the disaster flick’s greatest achievement is how it manages to appeal to American audiences of every political persuasion despite the fact that it’s conservative propaganda from start to finish, a kind of MAGA fever dream conjured out of Americana, anti-intellectualism, and rocket fuel, and, as I will argue, one of the greatest American films — as in, about America — ever made. Despite all this, I, a raging progressive, adore it, reference it endlessly, and bawl my eyes out like clockwork throughout this loud, gloriously over-the-top 141-minute ode to patriotic badassery, working class losers, and daddy issues. Let’s talk about why, but also what Armageddon might have to say about the so-called Greatest Country on Earth…

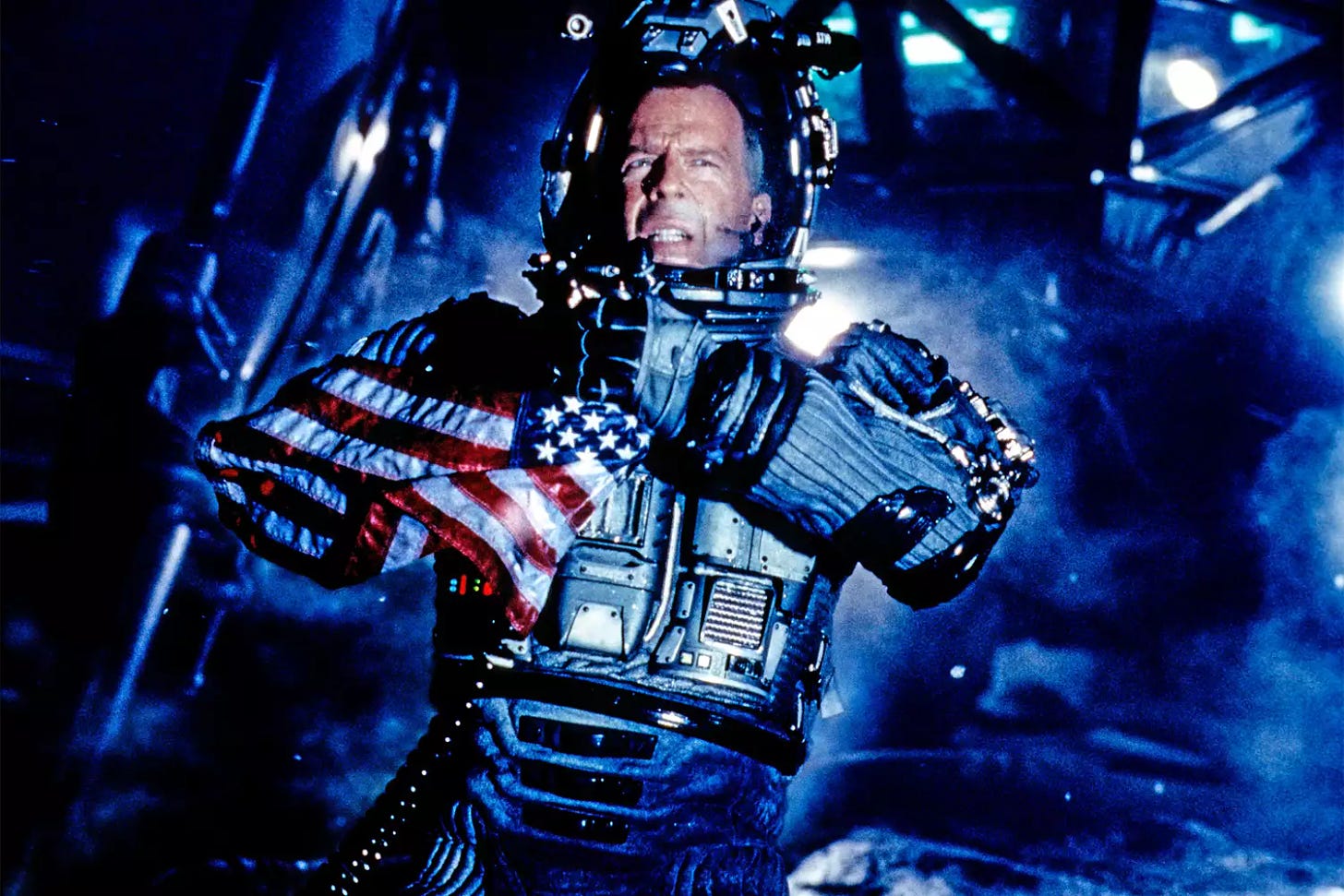

Armageddon was released on July 1st, 1998, to coincide with that biggest of specifically American holidays — the Fourth of July. The film’s premise is simple: an asteroid is going to smash into Earth and, for all the scientific community’s achievements, the best hope for humanity is a team of roughneck oil drillers who must intercept said asteroid, drill 800 meters into it, and drop a nuclear bomb down the shaft. It’s worth noting that the asteroid that crashed into the Yucatan Peninsula, wiping out the dinosaurs, was about six kilometers in diameter. The asteroid Harry S. Stamper (Bruce Willis) and his roughnecks have to blow up is 1,000 times bigger than that. Because everything in Armageddon is about size…kind of like how a certain kind of American defines their identity by how big their pick-up is. If it’s just impressive, that’s not good enough for Michael Bay. Dial that shit up – not to eleven, but eleventy-thousand!

This is not a criticism of the film as an experience, mind you. Armageddon is the 20th century American philosophy unapologetically transmuted into celluloid. Bigger is always better, whether we’re talking weapons of mass destruction or a McDonald’s meal. Super-Size Cinema, basically. It’s the response every idiot American gives when Europeans complain about the United States’ lack of universal health care – “Oh yeah, so why’d we have to save your ass in World War II?!” Almost every single gorgeous frame is composed with this in mind, to create a sense of awe of everything that the U.S. has achieved and will achieve in the future.

Consider the following. Near the beginning of the film, Japanese investors arrive to tour Stamper’s oil rig. Token female character Grace Stamper (Liv Tyler) shows them around as they ooh and ah at the impressive scope of everything around them as if they’re ignorant of how their own industry works. The U.S. flag, whenever it appears, seems several times larger than normal flags, swallowing up the sky and glowing with God’s divine light passing through them. NASA didn’t just build Stamper’s team one ginormous jet-like space shuttle – it built two, yee-haw, America!

For audiences outside of the U.S., the experience of Armageddon is, of course, less defined by the American obsession with its own awesomeness. For those who have been victimized by the country’s war machine, it is, no doubt, a deeply offensive film in its coded celebration of American superiority. For the country’s allies, the relationship with the film is more complicated, one more akin to envious terror.

It’s worth noting that in Armageddon, most other countries aren’t initially informed of their impending doom, to avoid global panic, instability, and a collapse of those all-important markets, but all this does is reinforce the idea that all these other countries, many of them filled with socialist pussies (forgive this word, but I’m using it in the redneck pejorative for effect), lack the will and/or ability to contribute to the saving of the planet. The U.S., it turns out, has allies in name only. There’s no such thing as a problem this super-power can’t handle all by its lonesome – just like John Wayne. Should I yee-haw again?

At this point, you might be asking yourself, “But, Cole, I thought you said you loved this film? It sounds an awful lot like there’s a lot about it you find deeply offensive.”

Well, there is.

But there’s a lot I find deeply offensive about a lot of pieces of art that nonetheless also deeply move me because I carry multitudes inside me.

American cinema is no different because imperialism, dressed up as patriotism, is an intrinsic part of its history – whether we’re discussing its Westerns, its jingoistic shoot-em-up action films of the ’80s and ’90s, or its ongoing love affair with war films about how, like, heroic and noble its military is. For example, both Top Gun films are fascinating character studies about stick jockeys getting into aerial dogfights. They’re also flag-soaked advertisements for how tough the U.S. Navy and the U.S. itself is, so go ahead and enlist to go fight in other countries for always ethically dubious reasons, kids (there’s a reason the military cooperates with films like these). Even anti-war films like Saving Private Ryan somehow manage to remind us how great America really is because of how militarily mighty it is.

Something to remember is, it’s possible for a piece of art to be both great and problematic. I know this dichotomy frustrates many people who want to view the world as black and white, but that’s a bifurcated view of reality that’s been increasingly forced on us by politics over the past fifty years. Reality is actually quite messy. Black and white often reveal something more like (gasp) gray, in turn forcing us to constantly make new ethical and moral decisions rather than just pointing to some reductive list of commandments or holy leader to do the work for us. The upside is that this also allows art to evolve with us over time, changing with our culture, taking on new meanings and even revealing itself in new ways we might’ve missed when we were all a little less…well, naïve. In other words, it grows with us.

Armageddon is no different.

Before I continue, I want to make something clear: I do not believe Bay has ever consciously set out to inject politics into his work. Nevertheless, he is an incredibly political filmmaker because his work is informed by his worldview. But the twist is, his worldview isn’t Republican, which you could think I’m arguing. No, his worldview is located at the intersection of spectacle, America’s heartland, and teenage boys on a Venn diagram.

In this regard, Bay might be the most existentially American director ever.

But in this accomplishment, his films are often predicated on promoting an idea of the U.S. that is so masculine, so steeped in iconography of a bygone era, and so anti-intellectual as to inadvertently become political statements. Call them incidental propaganda for American greatness. Again, this is not a criticism as much as an observation that Bay doesn’t disagree with.

Consider Armageddon, the subject of this conversation. NASA, the literal rocket scientists who put human beings on the Moon, are absolutely perplexed about how to save humanity from this Texas-sized asteroid. When scientists are asked for solutions, they suggest ones so ludicrous that they’re mocked onscreen. Other scientists seem confused about how to use their own equipment, forcing Stamper to explain it to them. Still others are identified as “Dr. Nerd” in the credits. Dr. Nerd? The disdain for actual science is relentless.

But interestingly, Armageddon’s disdain extends to other authority figures, too. The U.S. President is presented as a threat to Earth’s survival, unwilling to trust NASA’s crazy plan to have roughnecks blow up the asteroid. Members of the U.S. military are constantly presented as rule-following clowns willing to doom humanity rather than do the commonsensical thing – which is always to trust a team of roughnecks, most of whom seem to possess the intellectual and emotional sophistication of…you guessed it, teenaged boys. I’d add the destruction of New York City and Paris to this list, artistic/cultural hubs that dictate what’s sophisticated/intelligent.

It all comes back to wish fulfilment – or rather, cinematic validation – for blue-collar Americans. Don’t trust people with fancy educations who drink wine and visit museums. Don’t trust the government; you know they’re all corrupt, out to get you, the real bad guys of your story. Don’t trust anyone who doesn’t have dirt under their fingernails – like Stamper’s roughnecks.

Fun anecdote from Armageddon’s DVD commentary. Star Ben Affleck was as confused by the plot device of putting miners rather than astronauts in space, obviously missing the thematic resonance the former would have with audiences.

Ben Affleck: "Wouldn't it be easier to train astronauts to be miners, instead of training miners to be astronauts?"

Michael Bay: "Shut the fuck up, Ben."

The stakes in the film reflect Bay’s commitment to the U.S.’s heartland, too.

Over and over, we’re hit with images of rural and similar small-town communities as the music swells. All of these shots could work just as well in a period film about the Cuban Missile Crisis or even World War II, since we’re looking at ancient pick-ups, families gathered around old-timey radios, and kids in overalls running past J.F.K.’s grinning face. The past, it would seem, resonates more than the present when it comes to Bay’s target audience.

All of this represents an idea of what the U.S. really is. White farmers, other hard-scrabble types, people who’ve never been to any of the cities we’ve seen blown up already in the film. They’re what matters, it would seem. In making them the proxies for the audience in the film, they become the stakes.

In other words, Stamper and his roughnecks are saving these people. Everyone else in the film, even the shots from around the world, feel tacked on, irrelevant to the plot, present to add scope but nothing else to the film.

You see what I’m getting at yet? Armageddon is set in an alternate reality of the U.S. where the country is the center of the universe, authority and scientific expertise are not to be trusted, the only four women present are poorly drawn and/or fetishistic (my favorite is a stripper named Molly Mounds), almost everyone is white, and its greatest heroes are blue-collar men.

It's the MAGA dream come true.

Again, I don’t think most of this was what you’d describe as conscious constructs on the part of Bay. I’m also not going to fault the guy for somehow upturning how Hollywood worked in the ’90s by producing a film with different demographics, though we like to pretend every filmmaker could’ve singlehandedly fixed systemic racism/sexism in the industry at the time. But everything I’ve just described are expressions of how he views his target audience, what they react to, and his efforts to provide them the coolest fucking experience under the sun.

All this said, I think it would be a terrible mistake to reduce Armageddon to spectacle porn for its target audience or even a piece of prototypical MAGA propaganda thanks to the benefit of hindsight. It’s evolved beyond what Bay probably ever intended for it anyway, as all great art does. Instead, I look at it as a reflection of American tastes and changing politics in the late 20th century, and in this regard it is a stunning triumph.

Let me explain that another way. In 1998, you could look at Armageddon as the explosive swan song of an idea of the U.S. that had been dominant for too long. In 2024, you can look back at it as a vision of what the country could still become…if only someone came along to make it great again. Who knows what it will be viewed as from the vantage point of 2050? Whatever the case, I expect we’ll still be studying it.

If we accept that Armageddon is propaganda (and it is), then we must accept that its message is one with great appeal, both at the time of its release and, as we’re still discussing it, today. I’ve just laid out all the ways it plays to the MAGA crowd, but for those of us confused by the racist, misogynistic, and ultimately fascist precepts of this movement, I would suggest it a mistake not to look at ourselves in the mirror, too.

The United States is a country built out of myths and symbols. Many of these stories contradict each other, especially when we begin to consider the role of non-white people and sub-cultures within it. The U.S. isn’t actually just one idea, after all. But the problem is, white Americans have spent the vast majority of the country’s existence being encouraged not to interrogate or even acknowledge the flaws of their sacred cow. Education is, of course, key to developing such skills. It’s why Republican politicians are so determined to control what students learn in U.S. classrooms; you do not want your population questioning Big Brother, after all, so you try to control the state’s message as much as possible.

In my case, I was only twenty-two when Armageddon hit theaters. Like everyone else around me – including my young friends of color – I enjoyed it for its chaotic, often incoherent, but always thrilling story, sentimentality, and spectacle. More, it spoke to young men who, regardless of how healthy their relationships are with their fathers, always seem to be suffering from some kind of intergenerational daddy issues. The tear-soaked final moments on the asteroid, before Stamper saves the life of Affleck’s character always bring tears to my eyes, even today. It’s just one of at least a dozen moments in the film that make me tear up, in fact. Despite how improbable the plot is, despite how cobbled together scenes can feel, despite how time and space are often defied for the sake of a cool movie moment, Armageddon was – and remains – an extraordinarily fun film that skillfully preys on my nostalgia for the U.S. I thought existed when I was a kid.

But as I’ve grown older, as I’ve come to better understand how I was indoctrinated into the U.S.’s weird flag cult as a child by forces beyond my control, it’s become easier to also understand that much of what I reacted and continue to react to in Armageddon — those beautiful images of Americana, the “real Americans” saving the day like Hulk Hogan’s theme song — is a kind of propaganda meant to perpetuate a false ideal of the country. A false ideal that directly correlates to the MAGA movement. In some ways, I’ve even come to believe the film could be a vital tool, a kind of cinematic Rosetta Stone, to help us better understand the fantastical alternative reality MAGA supporters live in.

It's also just a lot of fucking fun, regardless of your politics.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Truthfully, I liked “Deep Impact” better.

But there’s a lot I find deeply offensive about a lot of pieces of art that nonetheless also deeply move me because I carry multitudes inside me.

Thank you for this.

I think you need to do The Rock and the first Transformers sometime.