A Matter of Survival: How the WGA Is Trying to Save Feature Screenwriters

John August and Writers Guild leaders weigh in about the exploitation of feature screenwriters and the contract proposals that would help them...and the whole film industry in the process

Will Appelbaum had three months left on his WGA health insurance plan when he delivered his feature screenplay to a studio that shall remain nameless here. His contract only guaranteed one step, known colloquially around Hollywood as a one-step deal, but what concerned him at present was getting his employer to pay him for the work he had already done. More was on the line for him than his business partners, agents, or lawyers understood that January. His life, to be precise.

Will told me his story over a phone conversation as he washed the evening dishes (which he apologized for multiple times, worried the sound of it was disturbing me).

The weeks passed with no response from the studio, and March 31st, the last day he could meet his union’s earning requirements to maintain his health insurance, inched closer and closer. He became increasingly nervous as they did.

Then, a call from his agent. This was in February, more than a month after he emailed his screenplay off to his studio executive. The studio had notes, which isn’t unusual. Nor was their request, frustratingly. They wanted a free pass on the script before they would officially accept delivery.

In other words, the studio wouldn’t pay up until Will executed their notes.

The Writers Guild of America has rules that ensure this never happens, but, of course, all screenwriters know studios, streamers — anyone with deep pockets — are the ones who really dictate the terms. Your representatives will almost always pressure you into doing this free work — “It’s just the way it is, everyone does it,” they say — and is the price we all must pay to “make it” in Hollywood.

Will explained to me that there was no choice but to do whatever he was told. The studio knew how worried he was about losing his health care, so they used that as leverage.

But even after that second draft, there were more notes, of course.

By March 29th, Will was shitting himself, to put it bluntly. In a few days, his life was about to fall apart. His agent and lawyer had even gotten involved, imploring the project’s studio exec for help.

Finally, the news came. Delivery of the draft had been accepted. Crisis averted…for now.

None of this should’ve ever come to pass, but it’s what inevitably occurs because of one-step deals. It’s not that free work didn’t exist before them, but these days, without a once-standard guaranteed second step to ensure the studios and streamers’ investment in a project, producers and studio execs are incentivized to strong-arm free work out of screenwriters instead.

In the case of Will Appelbaum, what no one involved understood — not even his agent and lawyer — was that he has a life-threatening medical condition. He kept this condition hidden from the Hollywood community at the time, for fear of how it might impact his employment. Sure, there are protections against this kind of thing; but there’s also this thing called reality. This is why, I should point out, he is not using his real name in this article, for fear of harming his professional future.

What Will’s studio employer had done was imperil his ability to medically care for himself, had literally put his life and his family’s well-being at risk, all because it knew it had the power to wring more free drafts out of him. This kind of story, far more common than you might think, goes to the heart of some of the rejected contract proposals that led the WGA to go on strike.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH U.S. FEATURES TODAY

Screenwriter John August has been in the business since the nineties; he’s written everything from BIG FISH to, most recently, ALADDIN. Many more know him as the co-host of SCRIPTNOTES. He’s also a member of the WGA’s current negotiating committee, which is why I turned to him to discuss what’s happened to the feature screenwriting business this century and what’s at stake in the current WGA strike.

“More than twenty years ago, when I was hired, my contract had a first draft, a rewrite, and a polish – and those three steps were crucial because that let me turn in a draft that was sort of my first, best effort and then get the notes from the studio about what they wanted to see,” August explained to me over the phone. This process allowed him to hear notes, implement them, and refine his work. “It really felt like I was a partner, a collaborator, in trying to get this project from an idea into a real movie. That was an incredibly important training ground for me because it let me, you know, learn the difference between writing a script and writing a movie.”

Hollywood’s studios and streamers evolved away from three-step deals in the aughts, then away from two-step deals in the teens thanks in large part to the machinations of business affairs departments. This means screenwriters are now left with one attempt to deliver the goods to their employer, to give them a film they might want to green light.

Well, on paper, that is.

Because the consequences of this change have decimated screenwriters’ lives and endangered the future of the American film industry.

WGAW Vice-President Michele Mulroney, herself a feature screenwriter (SHERLOCK HOLMES: A GAME OF SHADOWS), told me over email that the one-step deal, like many of the moves taken by studios and streamers to erode screenwriters’ income and security, were first sold as a positive when business affairs lawyers began to introduce them a decade ago. Writers would get chances they might not otherwise have (which is how my only one-step deal was sold to me by my reps, by the way).

“There was a sense that these deals allowed studios to mitigate risk – ‘What if the writer isn't up to the task? At least we're only stuck with them for one step!’ – and, in some cases, to take risks on ideas that were not necessarily going to work as movies,” she continued. “They could hire someone for a single step just to give the idea a trial run. If it worked, great, if not, well they hadn't invested much money or time.” These deals, once exceptions, quickly evolved into the standard. “For writers, one-step deals have just become gateways to endless free drafts and have made it more challenging than ever to make their year financially.”

My friend Dante Harper, screenwriter (ALIEN: COVENANT) and WGAW Board member, confirmed for me over Zoom what Mulroney told me and what I had already begun experiencing myself by the mid-teens. Screenwriters are now expected to do much more work than he, or August, did back when they became professional screenwriters. “They're working twice as much making much less — when they're working at all. That’s the new state of affairs.”

Harper, who is a well-established screenwriter at this point in his career, contends with this just the same as emerging screenwriters without a name and reputation to push back with. He recently worked on a one-step deal, but to deliver it, he was cajoled into completing seven drafts based on producer and studio notes. Meaning, six free passes on the project.

This increasingly broken system encourages producers and studio execs to demand more and more free work. Where once screenwriters had multiple drafts to achieve a script that made the studio or streamer happy, there’s no assurance the project will remain in development after that first draft goes in. So “we only have one chance to get this right” becomes a hell of an motivator to agree to whatever producers and execs ask for.

Even the definition of “rewrite” has changed, Harper said, with screenwriters now regularly being asked to “rewrite” a script even as they’re told to ignore all previous drafts and start over. You have less time to deliver, and you get paid a fraction of a full draft fee.

What this means in practice is that studios and streamers hold an extraordinary amount of power over screenwriters and they regularly use it to extract free work from them. This is accomplished in many ways, chief amongst them refusing to officially recognize the delivery of drafts that would trigger payments less-established screenwriters desperately need to live. In the case of Will Appelbaum, his need to meet the earning requirements to qualify for health insurance through the WGA was used to more or less blackmail free work out of him even if depriving him of that health insurance could cost him his health and financial security.

THE DAMAGE THIS CAUSES TO SCREENWRITERS’ CAREERS

When I asked John August what one-step deals would’ve done to his early career aspirations, he paused to think for a beat. “I think the rational choice for me would have been to work in television and not to try to stick it out of features,” he told me, “because with only one step at a time, you just don't know when your next paycheck is coming, and you don't know how many of those projects are pitching on are actually going to land in terms of deals.”

Consider the following:

Median feature screenwriter pay has remained unchanged since 2018, but when accounting for inflation, screen pay has actually declined 14% in the last five years.1

“Minimum” fees vary, determined by if the script or assignment is original or adapted and if it’s a low- or high-budget project. Generally, this means we’re talking $42,366 to $106,571…but that’s for two-step deals, or how I broke into the business. By the way, you can find all this in the WGA’s Minimum Basic Agreement (MBA) with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

If we’re talking one-step deals, what this really means is $30,512 to $77,518.

From these amounts, you need to deduct 11.5 to 26.5% for WGA dues and representative commissions (depending on how many kinds of reps the screenwriter has: agent and agent; manager; agent, manager, and lawyer).

Then, deduct state and federal taxes unless you live in a city or county like Los Angeles with more localized taxes. (That is, unless your only income this year is this paltry sum, in which case you might fall below the poverty line and escape taxes…yay?)

Let’s just say you’ll walk away with between $22,500 to $62,000 for writing one draft of a feature film.

But because you’re doing this for such little money, that also means you’re less of a priority for your employer. For low-budget deals like these, the work can be stretched over unacceptably long periods — up to nine months on average, in fact. Now factor in the three to nine months it took you to land the job, all of which was free work predicated on the possibility you might end up employed one day.

At the end of it, a part-time job at Wendy’s would’ve been more lucrative and done far less to damage your mental and physical well-being.

THE HEALTH CARE OF IT

WGA members must meet earnings requirements to maintain their union-provided health insurance. During successful streaks, you can rack up extra points that allow you to survive down times. But if you’re not making anything at all, or you’re making so little due to one-step deals that monopolize all your time for close to a year, you will lose your health insurance.

This was the danger Will Appelbaum faced when his studio employers would not accept delivery of his draft. In his case, an insurance lapse alone would’ve cost him, by his estimation, $300,000 and potentially left him unable to even procure care and necessary medications.

THE GREAT MIGRATION (OR: ONE OF THE MANY EXISTENTIAL THREATS TO AMERICAN CINEMA)

More and more screenwriters flee the features world for television, as John August’s co-host on SCRIPTNOTES Craig Mazin did (Mazin now calls himself a features refugee, which is how the world got “CHERNOBLE” and, more recently, “THE LAST OF US”). I similarly jumped ship, shifting more and more of my development efforts to television where I had already had some success with a series I created called “DRACULA”. It broke my heart, given it’s cinema — not TV — that speaks most to me as a storyteller.

This low pay and subsequent migration to the small screen has a surprisingly deleterious effect on the features world, but not one that’s immediately obvious.

“Well, I think we can actually draw some lessons from what is happening on the TV side,” August said when I asked him to explain this. “One of the reasons why we're talking about the crisis of mini-rooms is we have a growing group of writers who have worked on three or four shows … but they've never been on set. They’ve never been in post. All they know how to do is deliver a script, and I can tell you as a as a feature writer who has had a lot of things made, my job is writing that script — but my job is also learning how to make the movie. I may not be credited as a producer, but I know how to work a project through all the phases of production, right? You know I've been on set and had to do sort of crisis emergency rewrites. Had to deal with actors who won't come out of their trailers until you can get something fixed for them. I've been in post for weeks helping to, you know, find the movie inside what was shot.

“These are all things that studios need experienced future writers to be able to handle,” he continued. “Unless they can bring up a generation who learn how to make those features, they're going to be kind of screwed.”

WHERE THE WGA HAS FAILED IN THE PAST

Feature writers have felt left out in the cold for years by the WGA’s Minimum Basic Agreements with the AMPTP. I’ve witnessed numerous screenwriters rail against the Guild about this during internal meetings, in fact, including a very passionate Craig Mazin. I asked Michele Mulroney about this and why this wouldn’t be the case in the current negotiations, especially given the prominence of issues such as AI (which I’ve written about here).

“Over the last several years, I have definitely seen a consciousness-raising inside Guild walls and amongst the membership around all things screenwriting,” she told me, after pointing out these very issues are why she originally ran for the WGA’s Board of Directors. “This negotiation cycle — on the heels of yet another dismissive MBA from the AMPTP in 2020 — just feels different. There's a level of solidarity and empathy across all work areas. TV writers taking a real interest in understanding features issues, features writers getting under the hood of comedy-variety issues, and all of us grappling together with the economic pressures brought about by the rise of the streaming model. And let's remember, about half of our features writers also work in TV these days, so they are also invested in seeing mini-room issues and other episodic issues addressed.

“All to say, I don't think in 2023 we're in danger of seeing features issues relegated to some back-burner. We are squarely in the features fight!”

HOW WE FIX THIS

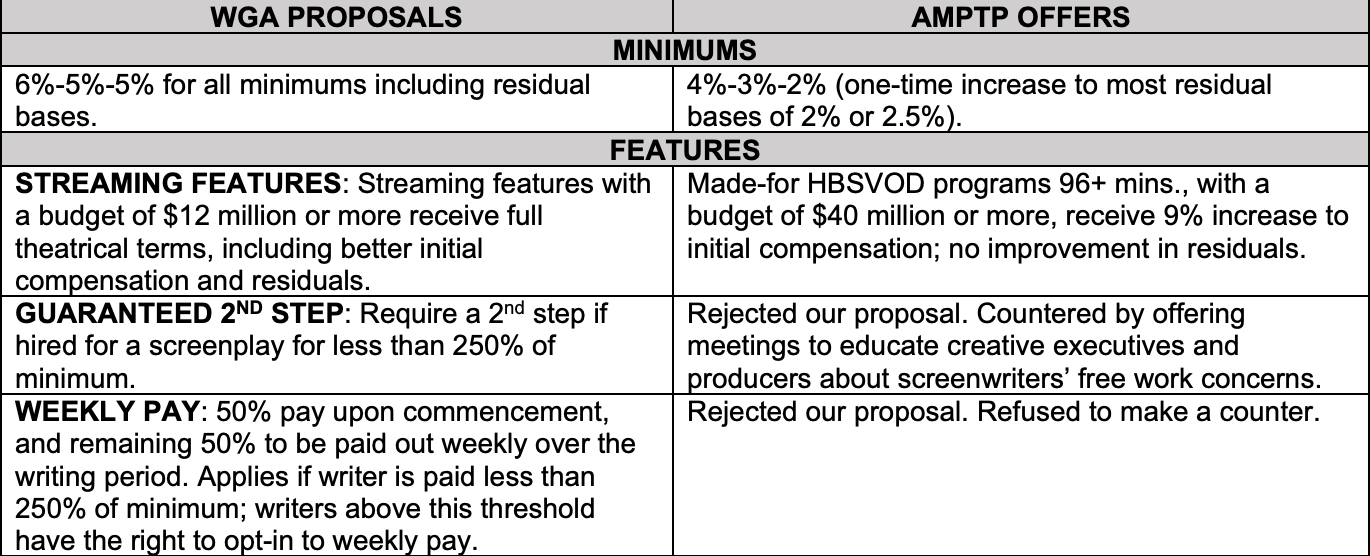

The WGA made three proposals to the AMPTP on behalf of feature screenwriters, two of which were roundly rejected. Let’s break them down.

GUARANTEED TWO-STEP DEALS

Even though Dante Harper believes the three-step contracts studios once used would be superior at producing a solid screenplay — “a natural way to make a good movie, it’s how we did it for decades” in his words — guaranteeing two steps in the WGA’s next contract with the AMPTP would provide feature screenwriters with more financial security for their work and better protect the quality of the scripts they’re being asked to produce.

But it’s fair to say the AMPTP…well…felt differently.

Michele Mulroney told me, “During negotiations, one of the AMPTP reps said their studio viewed the idea of mandatory two-step deals as ‘toxic’.”

These deals, it should be noted, are what produced all the great films of the seventies, eighties, and nineties that all studios and streamers cite today as a high point of American cinema.

“They wanted to retain the right to determine the duration of employment and were not willing to risk being saddled with a writer for multiple steps ‘if they're not delivering’,” Mulroney continued. “There was a failure to understand the fundamental iterative nature of screenwriting – that nobody gets it right in a single draft, that nowhere else in the business is someone given just one shot. Imagine an actor getting a single take. A director getting one cut of their movie. There are no one-step deals in TV pilot development because you will always need multiple drafts to get there. Only [feature] screenwriters are subjected to the pressure of delivering in a single draft and then being faced with either being replaced or pressured to do unending amounts of unpaid work.

“Because, of course, the studios do get their multiple drafts,” she added. “They just get them for free on one-step deals. That's the fundamental abuse we're trying to curb with our proposal.”

WEEKLY PAY

“The other piece of our proposal is also eminently reasonable,” Harper explained about the call for weekly pay for feature screenwriters. “It literally does not cost them a dime.”

Here’s how it works:

If your contract is for less than 250% of WGA feature minimums, you are paid 50% of your fee upon commencement and the remaining 50% is paid out weekly to you over the contracted writing period.

What this means is those of us making the least are guaranteed weekly earnings rather than waiting months, sometimes close to a year to get paid. If you’re one of the lucky bastards who make more than 250% of the minimum, you have the right to opt-in to weekly pay if you like.

This is what Harper meant by it doesn’t cost the studios and streamers anything. They just pay screenwriters what they’re contracted to anyway. However, what it does do is deprive our employers — and producers — of one of their most valuable tools to exploit us.

“A screenwriter delivers a script, and the producer has a lot of notes and wants to make a lot of changes,” Harper said, “and then, you know, suddenly, the writer’s making changes, doing notes, trying to be a good team player, while also running out of money — that final payment often becomes such a desperately needed thing that the writer will do pretty much anything to the script in order to get paid. Which is not how you get to a good script.”

According to John August: “If a writer has received 90% of their pay by the time they're ready to turn in that script, they just have a lot more leverage and I think that would be a game changer — not only for newer writers, but I think, you know, more experienced writers would also take advantage of that and recognize that it just gives them a better hand to say, ‘No, listen really, I am done here. Just like you as an executive are being paid on a weekly basis, I want to be paid on a weekly basis for the work I'm doing.’”

“This is the biggest carrot on the stick that many writers end up having to do,” Harper added. “Like, that's what forces people to do such epic amounts of free work. It’s also a perfect example of the irrationality and ugliness of [the AMPTP’s] initial response to our proposals — that they shot down an idea that doesn't cost them anything. They showed their hand, that the system is intentional and they prefer it as it is, because they know that they have you over that barrel.”

Leaving the power to imperil screenwriters’ ability to live with even a modicum of security in the hands of the studios and streamers also disproportionately victimizes WGA members who do not enjoy the status of someone like a John August. This concerns the actual August terribly. “We're asking the least powerful people to stand up against the most powerful people individually, time after time, to say, ‘No, no, I really do need to deliver. Give me my check.’”

This is, of course, what happened to Will Appelbaum.

A MATTER OF SURVIVAL

Michele Mulroney was stricken by the story of Will Appelbaum when I shared it with her. “It really hits on the absolute worst kinds of impact from free work abuse,” she said. “Sadly, it's all too common for our members to fall out of health coverage because they are waiting for a delivery check delayed by egregious free work requests. Or because they are prevented from getting their next job because they are mired in a world of free drafts and afraid of retribution if they say no. That's been a new and very unwelcome development in recent years — we are seeing way too many instances of a producer or exec telling a writer they are ‘not a team player’ if they dare to say they've done enough drafts and now need to turn in their work and be paid. Writers — especially emerging writers — are afraid of being labeled difficult or non-collaborative if they simply stand up for themselves. And sadly, reps are too often unwilling to step in and play bad cop to help the writer navigate these demands.”

Everything Mulroney just shared speaks deeply to my own personal experiences as an emerging screenwriter more than a decade ago, when everyone from producers who wanted more work from me and my own reps often made me feel I wasn’t being that team player. That I was the big D word – difficult. But however problematic this all might be, what happened to Will seems especially insidious. How many other feature writers have had their mental and physical health threatened and even harmed by this kind of parasitic capitalism?

Will was clear with me when we spoke that what happened to him was not the fault of a single studio executive. “My general experience is that execs are not indifferent in arch terms, but more institutional terms,” he said. “So, having protections through the WGA is what helps us combat institutional indifference. I think the proposals this time around on the feature side regarding weekly payment would have made this a non-issue. I would’ve qualified for healthcare by week seven of the contract terms, and then I could’ve just focused on what made the story better instead of scrambling to get my producer to submit the draft.”

Without these changes, the lives of feature screenwriters in Hollywood will only deteriorate from an already dangerously unsustainable level. More and more of these writers will either flee to television or abandon the business altogether, leaving America — the leading global producer of motion pictures for over a century — unable to compete in an increasingly international marketplace.

This is a common theme in the current WGA strike: this fight is about the sustainability of our industry, not today’s stock price. As John August told me, “We are trying to protect the pay and livelihoods of screenwriters, yes, but we're also trying to protect movies.”

You can read more about the WGA strike here:

The WGA Is on Strike — Here’s Why We’ll Win

Why AI Is the Most Important Issue in the Writers' Strike

The Tragedy of Howard Rodman Sr. (or: Why the Writers Guild Is on Strike)

The Secret Weapon Helping the Writers Guild Win This Strike

The WGA Strike in Photographs: A 'People's History' by J.W. Hendricks

If these articles added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

https://www.wgacontract2023.org/updates/bulletins/writers-are-not-keeping-up