A Rare Phenomenon: When Recording the Artistic Process Becomes Art Itself

What about when one artist attempts to capture another artist’s process as a historical document and, in doing so, creates a distinctly new piece of art?

Making art about the process of artistic creation has been commonplace for several centuries now, ever since painters realized their fascination with self-portraiture could seem less narcissistic if they painted themselves in the act of painting something else. Ta-da, now it was “art”. Here’s one I enjoy from one of my favorite Renaissance artists Artemisia Gentilsechi:

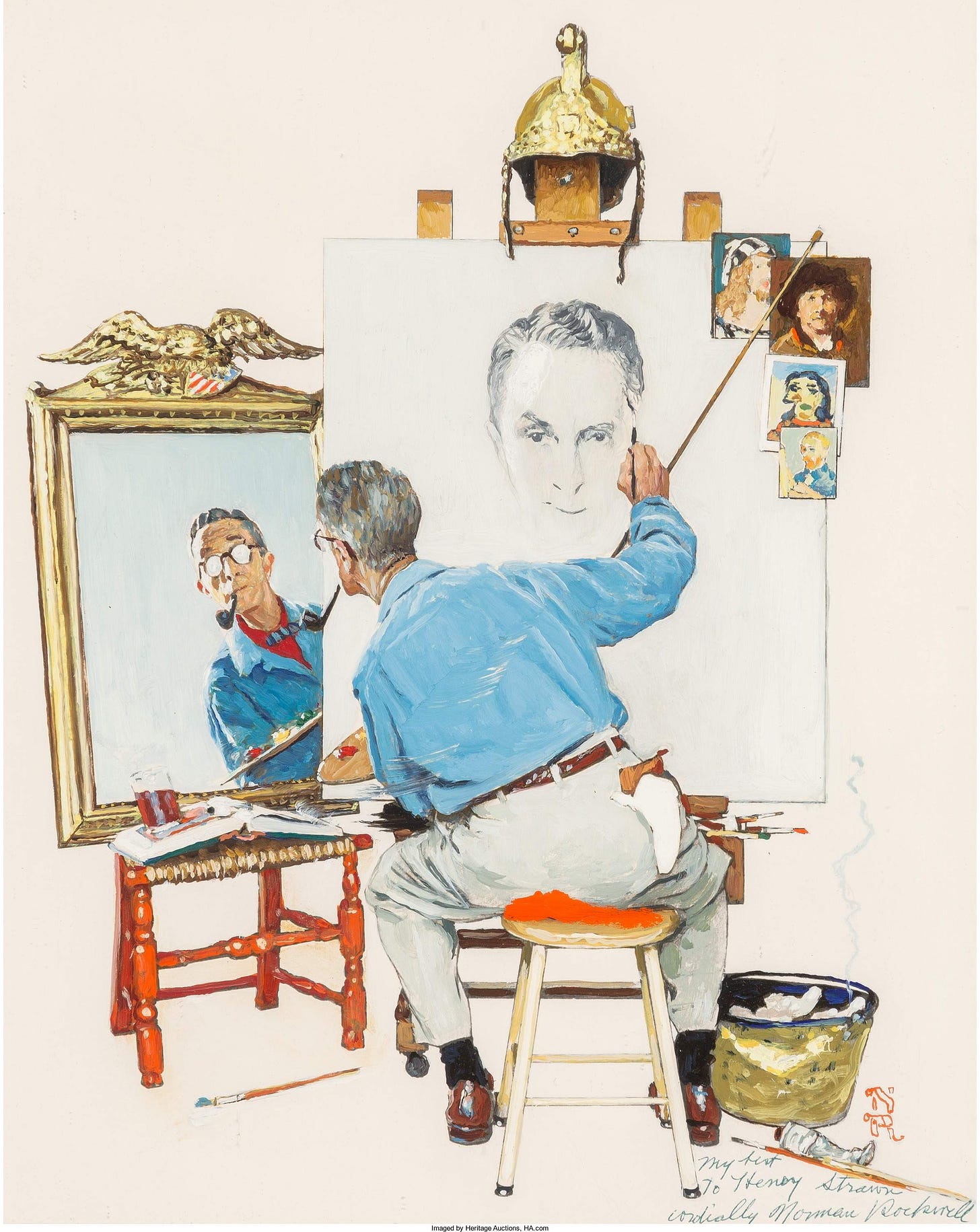

In the 20th century, Norman Rockwell somehow found a way to get even more meta about this specific creative kink:

Notice, in both cases here, the self-portraits somehow commented on and even illuminated who both Gentileschi and Rockwell were as artists? They’re far from just being their equivalent of “selfies”.

When it comes to filmmaking, directors have been exploring their own cinematic struggles through both autofiction and autobiography for as long as the medium has existed. Federico Fellini gave us one of the greatest examples of this with 8½ (1963). A few years back, Joanna Hogg bared all, metaphorically speaking, with her superb THE SOUVENIR (2019). Last year, Steven Spielberg made us all wonder how much of the cinematic genesis depicted in THE FABELMANS (2022) was true.

But these are all examples of searching for something like truth through fiction, trying to make sense of one’s own cinematic obsession and craft through the application and manipulation of both.

What about when one artist attempts to capture another artist’s creative process as a kind of historical document and, in doing so, creates a distinctly new piece of art?

This is what we’re going to discuss today. It’s a far rarer endeavor, and certainly almost non-existent before the moving image. For example, “THE OFFER” TV series, about Francis Ford Coppola’s struggle to make THE GODFATHER (1972), would not qualify. It makes no pretext about being more preoccupied with facts than telling a good yarn, which you could also say about those other examples I provided — 8½, THE SOUVENIR, and THE FABELMANS — or other “art biographies” such as THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY (1969) or GIRL WITH A PEARL EARRING (2003).

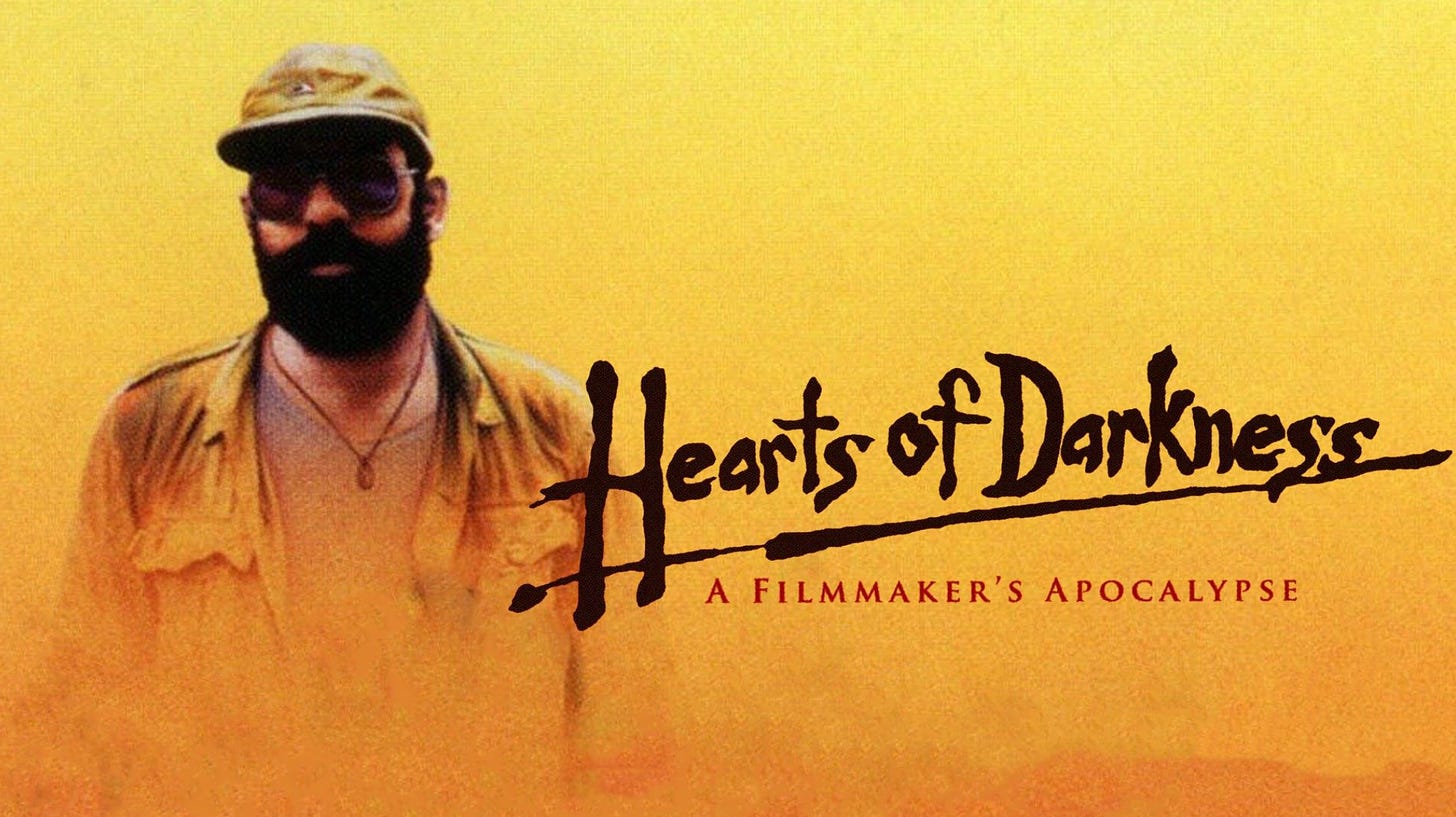

On the other hand, HEARTS OF DARKNESS: A FILMMAKER’S APOCALYPSE (1991), the documentary film about Coppola’s struggle to make APOCALYPSE NOW (1979), is an example of what I describe – a historical document of the artistic process that transcends the sum of the facts it presents to become a great piece of art in its own right. Some even argue it’s superior to the artwork it’s based on. More, when paired with APOCALYPSE NOW, both experiences are richer because of their relationship.

This is all my long-winded way of saying I want to share with you an example of this — a rare one from before the 20th century — that I recently discovered at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (in Sydney, Australia). It’s by Basile Lemeunier (1852-1922) and concerns his painting PORTRAIT OF ÉDOUARD DETAILLE (1891).

Édouard Detaille was, like Lemeunier, a French artist. The two were contemporaries. In 1891, the same year Lemeuneir painted the portrait in question, Detaille painted one of his masterpieces – VIVE L’EMPEREUR.

VIVE L’EMPEREUR is a mammoth piece, oil on canvas, that depicts the cavalry charge of the French 4th Hussars during the Battle of Friedland that took place, as you most certainly know, on June 14th, 1807. After all, this is common knowledge. Okay, not really. I don’t care about these details myself, at least with regard to this essay. What’s important is that you understand this is a big, imposing painting that wowed people when it was first displayed in Paris and the Art Gallery NSW bought it in 1893.

I first saw VIVE L’EMPEREUR when I moved to Sydney back in 2002. It’s impressive enough. I’m not a giant admirer of military/imperialist art, but I always found myself pausing in front of it when I passed through the museum.

When my family returned to Sydney in 2021, I visited the Art Gallery NSW for the first time in more than a decade and discovered VIVE L’EMPEREUR still on display. But something had changed, as I’m about to explain.

In 2014, the Art Gallery had purchased Lemeunier’s PORTRAIT OF ÉDOUARD DETAILLE. I’m not an art historian, but I think it’s fair to say Lemeunier’s oil on canvas painting was not the subject of a violent bidding war when it went to auction. It’s perfectly lovely, but, by itself, without context, a curiosity, the kind of painting you grunt with vague interest at when you first see it, and not much more.

The Art Gallery NSW had hung Lemeunier’s PORTRAIT OF ÉDOUARD DETAILLE next to Detaille’s VIVE L’EMPEREUR. It can’t help but look diminutive next to the painting beside it, but it also somehow manages to grow in size and scope and relevance because of this pairing.

Because Lemeunier’s portrait of Detaille depicts Detaille painting VIVE L’EMPEREUR. In fact, they were both painted in the same year.

Separated for more than a century, they are now reunited. Detaille’s masterpiece and, beside it, a painting that can best be described as a historical recording of the act of creating it. Lemeunier, of course, embellishes his work, imbuing it with details and decisions that distinguish it from an iPhone photo of the event, but the effect is generally the same, relatively speaking.

Interestingly, I would argue these two paintings only achieve true greatness when their meta-relationship is realized by this kind of proximity to each other. Hats off to the curators at the Art Gallery NSW who recognized this, invested a small fortune in purchasing PORTRAIT OF ÉDOUARD DETAILLE, and paired it with the artist and painting it’s based on.

Here’s a video I recently took of the two, followed by the paintings themselves for you to study in greater detail. What does their juxtaposition reveal to you or inspire in your own creative imagination?

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: