The Danger All Artists Face When They Leave Their Audiences Behind

Many don’t like to be challenged by ‘art’, but that doesn’t mean they should be dismissed when you create your own art

I recently stumbled across a vitriolic review of writer-director Todd Field’s much-celebrated film TÁR (2022). Given the concerning use of the English language and the misspelling of star Cate Blanchett’s name, one might come to some casual conclusions about the person behind it. But I think it’s a mistake to make such superficial judgments. In fact, by interrogating what motivated this response from them, an artist might begin to strip away some of their own culturally ingrained arrogance about a large segment of their potential audience. It’s a lesson I struggled to learn myself.

To begin, I’m going to say something that will sound hyperbolic…but it’s true all the same.

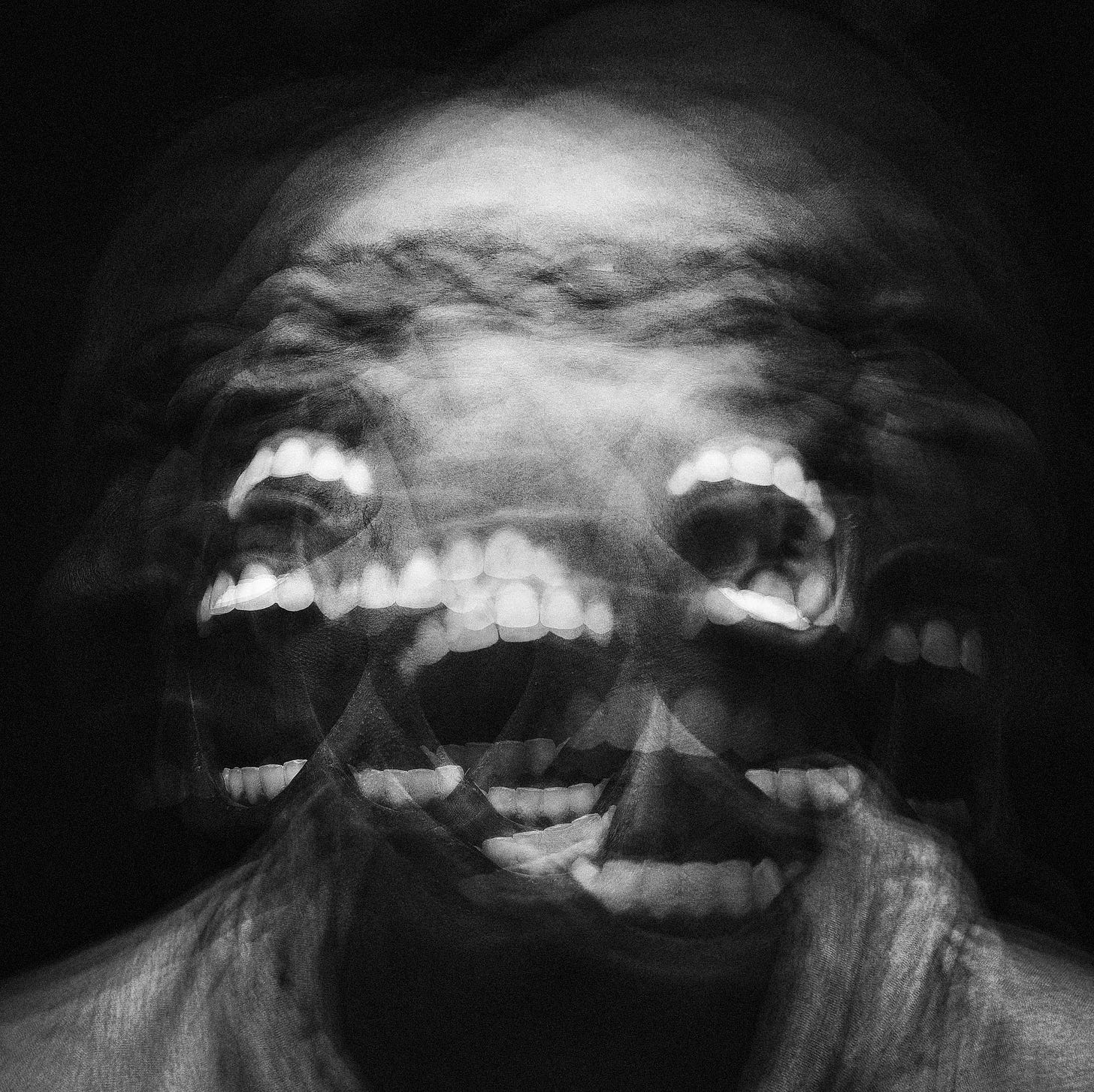

Art terrifies a lot of people.

A fiction author I call friend recently suggested to me the worst thing any author can do is “leave their reader behind”. What this means is, when a reader is made to feel they don’t get something, they can have three different reactions:

Reaction 1

Trust the author, work harder at the read, and, in doing so, hope to unravel the secrets of the universe — or, at least, the book in question. I tend to think that even if the author doesn’t stick the landing for their readers in this case, the read is still satisfying enough and, at worst, will get chalked up as a glorious failure. I read many authors whose work satisfies me even if, counterintuitively, I don’t actually like their books.

Reaction 2

Decide the book just isn’t for them and move on. No harm, no foul.

Reaction 3

Confronted by the mere possibility that they’re not smart enough to understand the book — an unacceptable scenario for many of us — decide it is, in fact, the author and their book that are stupid.

Reaction 1 is the dream scenario, Reaction 2 is just the reality of creating art, and Reaction 3 is…well, Reaction 3 is problematic because when a reader is left behind, as my friend describes it, they inevitably feel like their sense of themselves is being attacked and decide to go on the attack themselves.

In other words, you didn’t just lose a reader — you made an enemy.

More than a few times, I’ve heard authors, editors, and book agents attribute one-star reviews on Goodreads, Amazon, and the like to this phenomenon. I’ve heard similar from filmmakers and TV showrunners, too; art films like TÁR and ambitious, more literary TV series like, say, “SEVERANCE” will score tons of positive scores, but be equally maligned by angry viewers. Sometimes, campaigns are even formed to review-bomb such films or series.

Why would people feel so driven to shout violently about how terrible a piece of artwork is unless they had some emotional investment in convincing others it was terrible, too? The answer is, from my life’s experience, insecurity about their identities (I say this without judgment because, as I’ll get to in a moment, that insecurity is largely cultural programming).

Take the reviewer of TÁR in question here. They clearly felt attacked by their cinematic experience and believed the only way to defend themselves was to rage online about it.

Before you say it, sure, absolutely, art is subjective. Everyone has varied emotional and cultural responses to any piece of artwork. I’m not saying people can’t hate what they want to hate. But there are flags in this review that make it clear the words aren’t about TÁR, rather the reviewer’s own insecurities — maybe their own perceived intelligence, education, or economic class. Hell, maybe all three.

“Pretentious”, “self-indulgent”, or, my favorite, demeaning a subject matter by putting it in quotes. The “art of music”? The fact that the reviewer needs to believe music isn’t art suggests art itself scares him because if music is art, then music would be off-limits, too.

This sentiment is the result of more than a century of class warfare in many Western cultures (I abstain from discussing how it’s viewed in cultures beyond those I have a great deal of experience with).

For years, art has been portrayed as something produced for elitist types that the working class and economically disadvantaged have been indoctrinated to view with skepticism and even antagonism. They’ve been told what they enjoy is instead “just a movie”, “just a TV show”, and so on — just a bit of fun, entertainment, nothing more — anything to scuff and score the beauty of whatever they just enjoyed so that it can’t be mistaken for art.

Meanwhile, “high art” — foreign films, that shit they put in museums, stuff queer people revel in (homophobia being built into this, too) — has been dismissed out of hand because to indulge in such “degenerate art” would be a kind of class betrayal.

The easy thing to do is to dismiss people who refuse to engage with art as uneducated, incurious, and/or idiotic, but to do so is to assume your own role in the class war we are all born into. I did this for years, frustrated with the lack of imagination and curiosity within the community my family raised me in. At the end of the day, my solution was to simply go AWOL, to make a run for it and dive into the world — and art — on my own terms.

As for artists, I think the debate each of us must have with ourselves is what to do about audiences that aren’t interested in engaging with art because it challenges their own perceived identities, but do enjoy a “good book”, or movie, or TV series.

It’s not a question I have been terribly successful at answering myself, mostly because I don’t feel there is a clear answer given the arithmetic each artist uses to answer it is entirely unique to them. For example, the desire to pay bills or raise a family has forced many I know to “sell out” — it’s something I did a lot in my early career and less and less as I progress.

What I do encourage you to do is never dismiss these potentially antagonistic audiences, these disinterested “art critics” as beyond your reach. Take the time to understand them (the world is likely much bigger than your own perceived — and potentially arrogant — understanding of it). Most of all, don’t leave them out of your internal conversation about the art you intend to create even if you ultimately leave them out of the art you do.

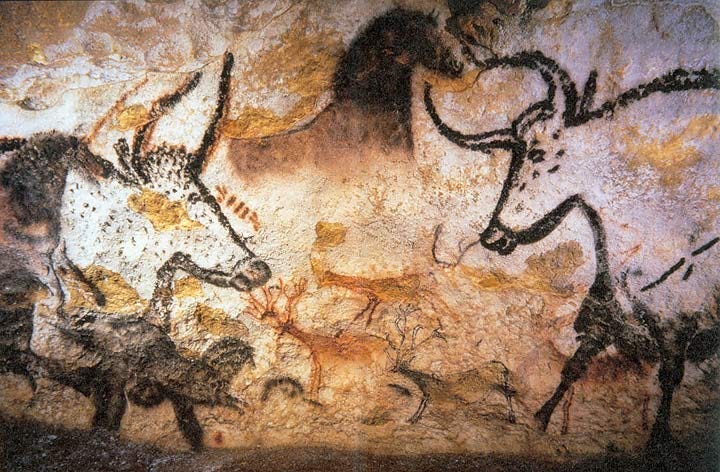

Because at the end of the day, art is (supposed to be) a mirror for our society, to show each of us who we are as individuals and as a culture so that we might better understand ourselves. The 17,000-year-old paintings on cave walls in Lascaux were not meaningless graffiti meant to improve an otherwise drab interior aesthetic, rather an attempt to explain and navigate the confusing and dangerous world outside. That is the artist’s job.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Tar was my favorite movie of the year, and I don't feel compelled to fight anyone over that because I know it was brilliant, nar, nar.

You can remain friends with favorite films and television programs and still regard the people who finance them as enemies. The question always remains, though: does the final say on what they are remain with those who first made them or those who made them famous?