The Church of John Wayne’s Star-Spangled Wang

The cowboy, the maverick, the vigilante — America has paid a high price for its hero-worship of the system-defying loner

I’m sitting in a TV writers’ room a decade or so ago, working with a white man who regularly complains about how biased Hollywood is against Republicans like him. But then I witness this same man argue that what America needs is more guns to a room full of writers mourning the recent murders of twenty children at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown.

“I don’t think it’s that they don’t like you because you’re a conservative, my man,” I tell him later. “Maybe they don’t want to work with you because they think you’re an asshole.”

The victimized white man, forced into a corner, left with no choice but to violently fight back alone to protect his home, his family, and his fundamental freedoms is a uniquely American myth. Like most American myths, its origins are only loosely tethered to reality and rely more on symbolism to perpetuate itself. And there is no greater symbol of this dangerous strain of patriotic hyper-masculinity in American history than actor John Wayne, who, judging by how he is invoked throughout the culture, packed a flag-wrapped cock in his drawers worthy of Sunday morning worship.

He is the ultimate good guy with a gun.

The ultimate tough guy.

The ultimate American.

My father seems frustrated when I ask him why there’s a handgun in the same cupboard he keeps cereal bowls. The answer is obvious to him.

“You never know who’s going to come to your door.”

John Wayne’s fifty-year-long career fixed the image of the cowboy, six-shooters hanging from his hips, in the American psyche, and in doing so spawned generations of white actors who cashed in on the swaggering penchant for violence and frontier vigilantism that Wayne had made accouterments of masculine character. None came close in his lifetime to achieve his status as a gunpowder-drunk action hero with the possible exception of Clint Eastwood.

All that can be said about Wayne’s tough guy with a gun persona in American culture can also be said about the country’s love affair with Clint Eastwood — in large part due to his portrayal of the character Detective Harry Callahan in the DIRTY HARRY series, a vigilante cop whose use of the Smith & Wesson Model 29 revolver (the .44 Magnum) to dispatch thugs was so popular with audiences, it led to a dramatic increase in the gun’s sales.

My father is complaining to me about American policing. The problem, he insists, isn’t the abuse of power or the murder of innocent Black men, as tragic as he concedes that may be. It’s that cops aren’t allowed to just get rid of criminals like they used to.

“You’ve got to ask yourself one question. Do I feel lucky?”

I’m watching my friend, a 320-pound Black man some 6'4" tall, hyperventilate loudly beside me in my passenger seat. The siren lights have only just appeared behind us on I-94 on our way out of Detroit. They play across the rearview mirror, the windshield, and his twisting, terrified face.

I was speeding.

“Well, do ya, punk?”

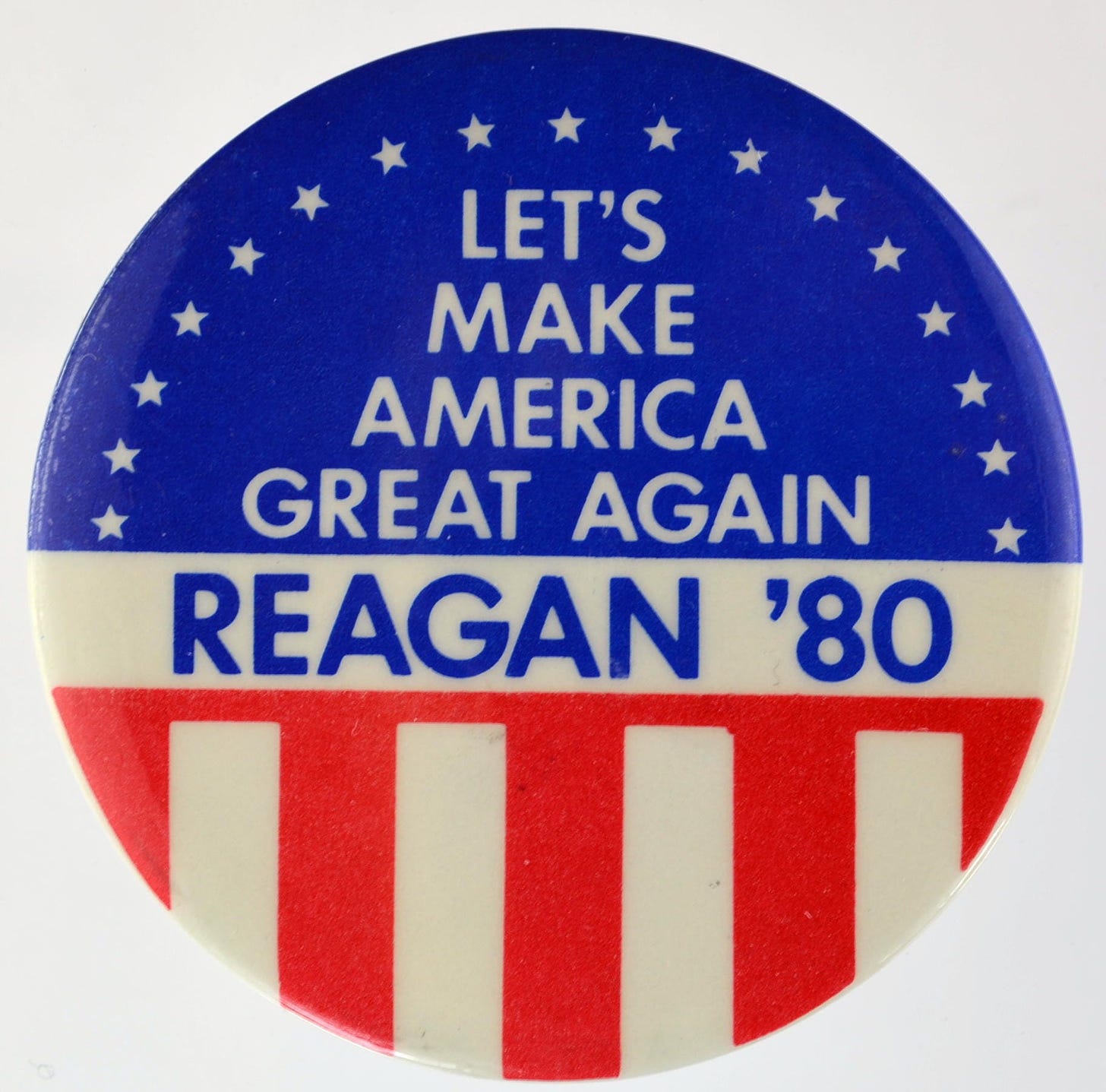

John Wayne’s death in 1979, at the conclusion of the seventies and thirty years of violent social upheaval, seemed to signal an end of what was “great” about America. Who was going to fight back against the “savages” seeking to overtake the country now?

When Ronald Reagan hit the presidential campaign trail a year later, he wanted to convince voters his career as an actor who played cowboys onscreen made him an actual cowboy — the type of salt of the Earth, shoot-first-ask-questions-later hero the country was hungry for after seemingly endless war abroad and civil unrest at home, White House corruption, and a catastrophic economic downturn. A sense of security needed to be re-established.

What Reagan was really saying to voters was, “I’m a man’s man like John Wayne, not like that wimpy liberal Jimmy Carter, and I’m going to bring some law and order — frontier justice — to Washington, to the streets of America, to your households!”

He understood, maybe consciously, maybe unconsciously, the country’s need for a strongman, for a good guy with a gun, for someone willing to fight back against the forces of social progress — equality — threatening the country’s traditional way of life. The system had turned on white America, specifically white men, and it was time to do something about it.

“The system” is always the enemy of the victimized white man.

FIRST BLOOD landed on screens in 1982, a thrilling story about a Vietnam vet-cum-drifter named John Rambo who is tormented by a small-town police department for daring to think he had a place in their society. He was one of the first white male characters to truly capitalize on the victimization theme, even if the filmmakers’ intentions were not so craven. After all, Rambo was a victim himself of an unjust war like hundreds of thousands of other American men, a forgotten hero despite his service and sacrifice. It was easy for many in the audience to superimpose themselves onto the white character as he fought back against such disrespect.

My father and every other Vietnam vet like him I know immediately celebrated John Rambo, leading to a 1985 sequel in which Rambo, tasked with returning to Vietnam for one last mission, asked his former commanding officer, “Do we get to win this time?”

Loss defines this question. Trauma. A universal sense of being wronged.

Recently, I penned an essay about the original TOP GUN (1986), arguing that hot-shot pilot Maverick was the film’s real villain and director Tony Scott intended his story to deconstruct toxic masculinity. The character only triumphs when he submits to the collective will of the system, his fellow pilots, and instructors.

When I share this essay in a few Facebook groups I belong to, I am immediately besieged by angry white men who are deeply offended at the idea that Maverick, someone they identify with, might not be a bad-ass hero. Some cite Maverick’s loner status as a strength, and instead point a finger at the system — his fellow pilots and instructors — for not valuing his unique talents more.

Again, “the system”. It’s the system that’s the problem. Anyone who fights back against it must be the good guy.

“Now we have a team of mavericks,” John McCain said on the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign trail, describing himself and his running mate, Alaska governor Sarah Palin.

“The original mavericks,” or so a TV ad will describe the Republican candidates not long after this.

“I’m John McCain and I approve this message.”

maverick

/ˈmav(ə)rɪk/

noun: maverick; plural noun: mavericks

1. an unorthodox or independent-minded person.

“he’s the maverick of the fashion scene”

2. a real American.

“fuck yeah!”

The maverick. The vigilante. The cowboy.

These all represent the same thing in the American character — a disdain for the so-called “system”, a distrust of elected officials who seek to govern, and an antipathy for the social compact that supports civilization.

This religious-like adulation of American loners, or outsiders, willing to challenge the system — even take up arms against it — extends beyond cinema to all other forms of art. In these cases, those who perceive themselves as victims of the said system almost always decide what these symbols mean rather than the artists who create them (such as in the case of director Tony Scott’s real point behind TOP GUN).

Perhaps the most egregious example of this is the embracing of Marvel’s Frank Castle/Punisher character by American police who celebrate the murderous vigilante as a hero and adopt his skull iconography.

Law enforcement officer Jesse Murrieta said, “Frank Castle does to bad guys and girls what we sometimes wish we could legally do. Castle doesn’t see shades of grey, which, unfortunately, the American justice system is littered with, and which tends to slow down and sometimes even hinder victims of crime from getting the justice they deserve.”

Ed Clark, the head of St. Louis’ police union, urged police officers to use a version of the Punisher symbol after twenty police officers found themselves the targets of an internal investigation.

Lexington, Kentucky Police Chief Cameron Logan insisted the use of the Punisher symbol on the city’s police cruisers “represents that we will take any means necessary to keep our community safe.”

I challenge an American cop I know about his strange hero-worship of the Punisher, pointing out that the Punisher’s co-creator Gerry Conway has repeatedly pointed out that the character is a criminal and a “symbol of a systematic failure of equal justice” — including the police. In response, he tells me I’m spewing more of my liberal bullshit, then stalks away, refusing to listen to me anymore.

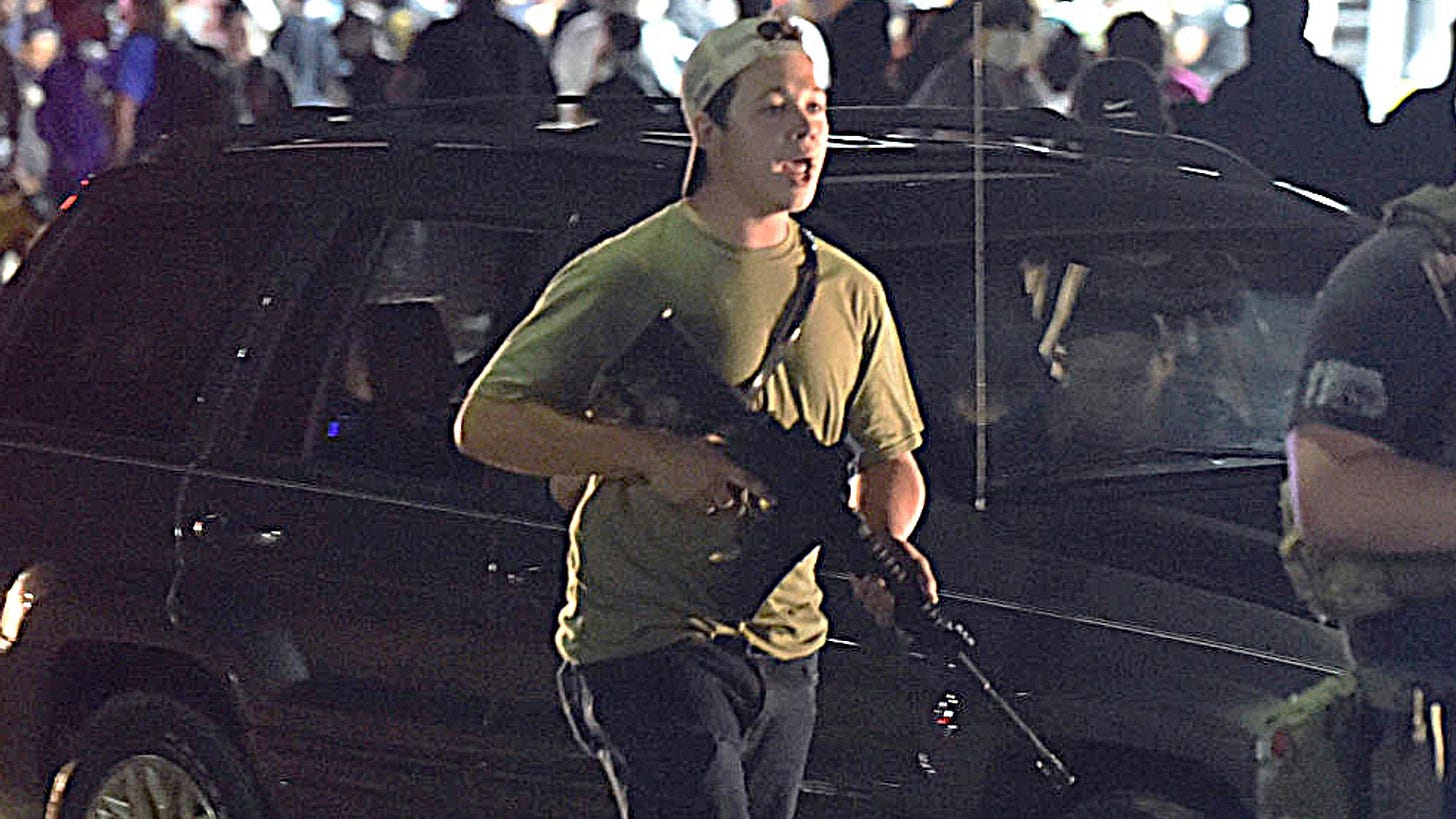

On August 20th, 2020, a white seventeen-year-old named Kyle Rittenhouse crossed state lines with multiple firearms, joined a group of armed citizens allegedly defending local businesses from a crowd protesting the shooting of an unarmed Black man by a police officer, and shot three people himself — killing two of them.

More than a year later, a jury accepted his claim of self-defense. Rittenhouse is now held up as a hero by many Americans, a good guy with a gun. He profits from his vigilantism because there are a great number of people who yearn to deal out some good ole frontier justice themselves, to return to the days when cowboys such as John Wayne patrolled the plains, to when real (white) men were in charge.

“Where is my John Wayne?

Where is my prairie song?

Where is my happy ending?

Where have all the Cowboys gone?

Where is my Marlboro Man?

Where is his shiny gun?

Where is my lonely ranger?

Where have all the cowboys gone?”

-Paula Cole, “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?”

Cole’s song is a critical commentary about men who abandon their families to escape into their cultural fantasies, which, in the context of the work, refers to white male fantasies. But in the twenty-first century, even feminist pop songs aren’t safe from symbolic redefinition. As Dr. Larry A. Van Meter put it in his book JOHN WAYNE AND IDEOLOGY, “[“Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?”] has metamorphosed into an anthem for an America pining for the lost masculinity that John Wayne ostensibly embodied. Such is the power of John Wayne, that even the deployment of the name itself manufactures an interpretation counter to the one offered in the lyrics.”

There it is again, that idea: loss. Implying a trauma, something that’s been surrendered or stolen, something that has to be taken back by force if necessary.

“Let’s make America great again!” Ronald Reagan pledged on the 1980 campaign trail.

The irony is that the very people who cling to the myth of John Wayne’s tough guy cowboy persona overlook the fact that it was manufactured by director John Ford — a cinematic mad scientist who ultimately decided he had let his Monster get out of control and sought to dismantle his toxic masculine identity onscreen in THE SEARCHERS. The Western — which most now considers Ford’s magnum opus and certainly the best film Wayne was ever associated with — is about an ex-Confederate soldier named Ethan Edwards who, in pursuing his kidnapped niece into Native American country, must confront his own racism and violent rage.

The now-iconic final shot of THE SEARCHERS sees the anti-social Ethan lurking outside the home of his brother as Max Steiner’s sorrowful score rises up and the Sons of the Pioneers sing, “Ride away, ride away…” The family inside never gives him another thought after he returns their child, and so he takes the song’s advice. He walks off, and the door closes behind him. “Ride away, ride away…”

Ethan is a throwback to the savage West…which must be left behind if family, community, and civilization is meant to move forward.

This is how Wayne’s cowboy story should’ve ended, a curiosity of a bygone era, worthy of study but otherwise left in our cultural rearview mirror following his death in 1979. But that’s not what happened, of course. He had reproduced by then, his hyper-masculine ideal continued to spread like a virus long after he was gone, and he took over a country’s subconsciousness.

“I am your retribution,” Donald Trump declared on March 4th 2023.

The United States is a country of myths, and none — with the exception of the Evangelical commitment to the idea that the Founding Fathers were trying to build a Christian nation — has been as successful at cultivating violence, inspiring anti-government sentiment, and stymying and eroding the country’s march towards what most would call progress as John Wayne and his star-spangled wang. It’s been fucking America for close to a century now.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

This was so good and fits right into the ideas of story and narrative that I was meandering about earlier this week. That's a goddamn mythic deep structure you are talking about, so much so that even Paula Cole gets co-opted. Amazing piece.

Thank you for your thoughtful article.

American Exceptionalism is literally killing us.