Every Screenwriter Eventually Faces a Hollywood Version of the Kobayashi Maru

I failed the 'no win scenario' test; now learn from my mistakes

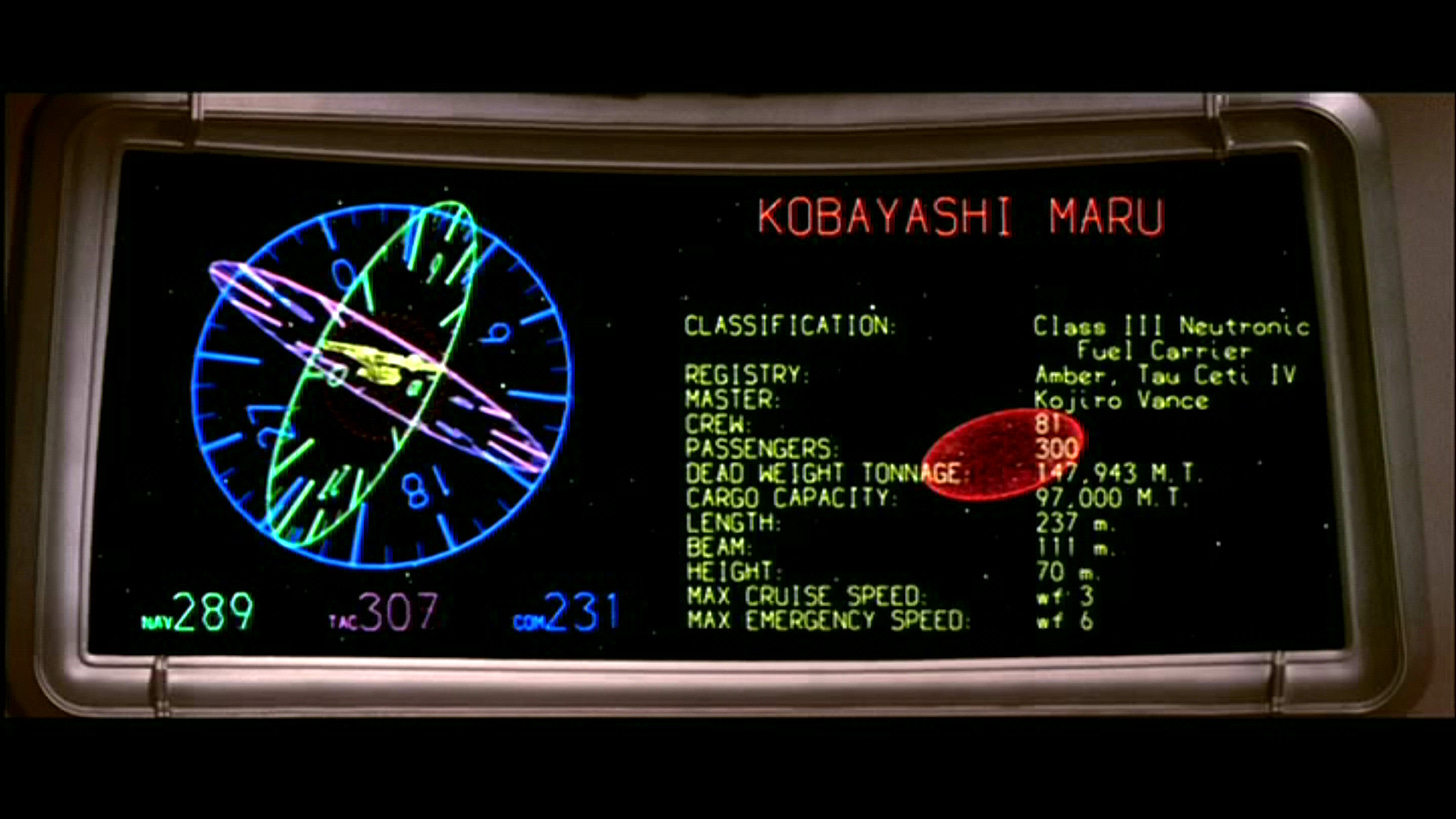

If you’ve seen STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF KHAN (1982), you know that the Kobayashi Maru is a “no win scenario” test all Starfleet cadets must face. It’s meant to be a metaphor for how we face life. But there is a Hollywood screenwriter’s equivalent, and this essay is about one I faced. I’ll describe it in detail, the outcome and consequences of it, and how my career responded.

But first, maybe you should check out the STAR TREK II scenes I’m contextualizing this piece with if you haven’t seen it yet.

As for my Kobayashi Maru scenario, here’s how it all started about a decade ago…

I’ve sold an original spec script to a studio. The studio loves said script, or so they tell me as we sit across from each other at a so large table you could assemble a million-piece puzzle on it. It’s my second script for this company, and it’s starting to feel like I’m their newest golden child.

Time to begin the second draft.

There are four sets of producers on my project. Two of them are heavyweights, both borderline legendary, in fact. All of them have thoughts about what is and isn’t working in my script. And all of them expect me to address their very different notes.

Bernard Hermann composed a lot of scores that convey the anxiety I felt at this moment (I prefer VERTIGO’s).

So, I come back to the four sets of producers with a list of solutions that I believe honors their very different notes. Unfortunately, two sets of producers disagree with me on this point. We discuss what the narrative priorities are, what I must address to start the second draft, and then I’m sent away to find the best way forward.

I return with a new list of solutions, including a new outline, that satisfies the discontented producers, except this time a previously happy producer — or so we all thought — now insists they’ve never actually felt heard and nothing about the spec ever really worked for them anyway.

Nothing?

But…but…you asked the studio to buy this project for you?

Anyway, I come back with another new list of solutions, including another new outline, only to discover three of the four sets of producers now aren’t happy even though all I did was execute what we all agreed upon in the previous meeting. At this point, I’m not even innovating. I’m just copying and pasting their ideas from notes they’ve provided, as some asked me to do.

Back to the drawing board.

Yet again.

This process continues, increasingly without any hope of resolution.

Ultimately, nearly a year in and months past delivery dates I was contractually obligated to meet, I sell another spec to the same studio — one I wrote while waiting to start the problematic second draft of the first spec! — which I then begin to work on new drafts of for the studio.

I’m never allowed to start the second draft of the first spec. It just dies, along with another little piece of my soul and will to work in Hollywood.

Okay, let’s step back.

The Kobayashi Maru scenario here was, of course, that there was no way I was ever going to start the second draft of my spec. Not with four sets of producers involved, all with different hopes and needs for the project. It was an unwinnable test for any screenwriter, but one I failed worse than I had to, I think.

Because in moving on to a new project with me, the studio quickly abandoned the old project — which meant more money for me, but an aborted job and, in this case, three sets of producers who faulted me for not getting the job done even though none of them could even agree what said job was.

Some of these producers still won’t work with me today, which likely won’t change unless I get nominated for an Oscar or write a movie that grosses half a billion.

If the Kobayashi Maru metaphor is to continue, the real questions becomes: how did I face this test, what did I learn from it, and what would I do next time? This is a subjective experience, of course, and I invite others to share their own Kobayashi Marus. But here’s what I know:

How did I face the test?

I allowed myself to despair, that was my first mistake. As a working-class kid from Detroit, I was distracted by dollar signs, how much I’d lose if I failed, what it would mean for my career if I did. All these things were inevitable, and, with experience and more wisdom, I would’ve recognized that sooner.

What did I learn?

In pursuing a career as a screenwriter in Hollywood, sometimes you win, sometimes, no matter what you do, you will lose. Some of us will lose big. But it’s the danger of the job, being victimized by politics and what amounts to bad luck.

It’s not always your fault.

What would I do differently?

I would’ve focused on one set of the big producers. In making them happy, in making sure they were always on my side, they could’ve served as advocates against the others. Instead, I tried to make everyone happy, which was never going to happen.

While I don’t believe that one set of producers would’ve made a significant difference to the project’s fate, I might’ve at least been commenced to write the script’s second draft, rather than lose that step and income. I might have also retained one of the producer relationships despite the debacle, too.

The take-away

Screenwriting as a career is, like life, all about the chaos.

In success, the chaos might become a bit more manageable, but it’s still there. You have to develop emotional tools and, ultimately, wisdom — I’d also advise support networks — to endure the Kobayashi Marus.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Why does a single project require four sets of producers?

This feels like a noob question, because there’s probably a thousand pages of rights and options attached to these things, but: Do you have any stalled/abandoned/development-hell-condemned projects that you’d ever consider returning to?