Q&A: Writer-Director Liz W. Garcia Found God on the Big Screen

The 'Space Cadet' filmmaker discusses her love affair with cinema and balancing her Hollywood work with her side hustle as an indie auteur

The first time I met Liz W. Garcia was in Los Angeles for a kids’ playdate, but she quickly revealed she wasn’t long for the city. She was imminently transplanting her family to Brooklyn, which made her the first Hollywood type I’d ever met to decide L.A. wasn’t for them and get the hell out. Liz, as I would soon learn, didn’t do things quite like everyone else in the business - which has made her something of an inspiration to me over the years. When my wife and I began to discuss leaving L.A. ourselves, her name came up often. “Liz did it, why can’t we?” But more than just geographically brave, she had also ventured into writing and directing her own films in the independent space. She hadn’t used indies to break into the Hollywood film/TV business like most people I knew. She used the Hollywood film/TV business to break into indie filmmaking. In an industry that encourages and rewards constantly going bigger, Liz seemed determined to do the opposite - and she’s found great success doing it.

This week, her latest indie film, Space Cadet, debuts on Amazon Prime. It follows Florida party girl Rex (Emma Roberts), who turns out to be the only hope for the NASA space program after a fluke puts her in training with other candidates who, yeah, may have better resumes, but don’t have her smarts, heart, and nerve. It’s preceded by the indies One Hundred Percent More Humid (2017) starring Juno Temple and Julia Garner and The Lifeguard (2013) starring Kristen Bell, both also written and directed by Liz. And in television, she co-created the series “Memphis Bell” in 2010.

Liz and I are about to have a sprawling conversation that focuses on, amongst many subjects, her complicated love affair with cinema as a woman, what it takes to emotionally survive the business (especially when reviews don’t go your way), and her decision to forge her path as a director by turning to independent film. For filmmakers from traditionally marginalized groups in film/TV, there will be a lot here that validates your own experiences and hopefully makes you feel less alone. For screenwriters and directors at all stages of your creative journeys, I expect you’ll find a great deal to take inspiration from, as well (I know I did); this is the story of someone who made a lot of risky, unconventional decisions to become the artist she wanted to be - which we can all learn from.

COLE HADDON: Let’s kick this conversation off with a fun question. I want to tell me about two films you love. The first, the one you bring up when someone asks, “What’s your favorite film?” and you, of course, defer to the one that intellectually inspired you in some way as a filmmaker and still does all these years later. The second, the secret love you’re too embarrassed to admit you watch far more than you should but you’re going to tell me all about today anyway. For context, my answer to the first question is Lawrence of Arabia and my answer to the second question is Krull, but also maybe, very possibly Just Friends - which is an unrecognized work of genius goddamnit.

LIZ W. GARCIA: I always say Rosemary’s Baby because that’s the movie that changed how I look at movies. Sixth-grade slumber party, my friend Carrie’s dad rented it because it was horror, but rated PG-13. The dream sequence where she’s raped by the Devil and is on a yacht with the Kennedy lookalikes - utterly trippy and bizarre and it blew my mind. That was the sequence where I first realized there was a person behind these movies, and that movies were art, that they were as subjective and malleable as paintings. I loved the movie then for being lurid, odd and daring. Then, I came to appreciate that this was a film using horror to tell a contemporary feminist tale about bodily autonomy. My guilty pleasure favorite movie? Dumb & Dumber. I could defend it to you, but let’s not do that. Let’s just hold space for the fact I’ve seen that movie top to bottom at least thirty times and select clips way more than that and when Jim Carrey tears up and says, “I’m sick and tired of being a nobody,” that is acting, folks.

CH: [Laughter] The juxtaposition of these two films is perfect. Okay, so maybe it’s because I’m currently on painkillers or maybe my brain has just gone to shit since I became a father – probably both – but I can’t remember anything about your story before Hollywood beyond the fact that you’re from Connecticut. Did you know film and TV were your destination back in high school, or did you work that out a bit later down the line?

LWG: I didn’t know I’d go into film and TV until the back half of college. I’d grown up loving to write – short stories, poems, plays – but saw it as a skill I’d use in some other profession like academia or journalism. I come from a family of imaginative freelance folks – artists, scientists – but no showbiz. Zero. So, even though I was very intense about “Twin Peaks”, “My So-Called Life”, Heavenly Creatures, Sex, Lies & Videotape - I didn’t even dream of working in the industry.

CH: What changed?

LWG: I took a film course at Wesleyan to fulfill a credit requirement and, after the first class, I knew that this had to be my major.

CH: Wait, I have to ask, what class led to such a dramatic transformation in you?

LWG: Shout out Ellen Nerenberg in the Italian Department at Wesleyan. The class was Italian and Italian-American Cinema.

CH: I like the sound of this class already.

LWG: She taught Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, which is the seminal text on the male gaze in cinema. There’s a lot to say about Mulvey’s theories, but for the sake of this conversation, I’ll just say that what really rocked me was that I had no idea we could look at film in this way. I didn’t realize that film bore the evidence of cultural values. This idea really spoke to me because it gave me a much-needed way in. The movies of our childhood were not made for me. A young white male hero is not a point of entry for me. So, as much as the medium intrigued me, I felt the exclusion in it. Manohla Dargis wrote a great piece about what it is to be female-identifying and love film, to love this medium that doesn’t love you back. So often that’s what it is for me. I want to love the movie you all love, but that movie doesn’t respect me. Have you ever been in love with someone who doesn’t respect you? Most women have. So, it can feel fucking foolish to go down that same path with your career, just gunning for that thing that just doesn’t even notice you. Look, I’m going a little tangent-y here—

CH: Please do.

LWG: Here’s a good example of why I needed to fall in love with film through this critical lens first. So, Scorsese is now one of my favorite filmmakers. But, since this is an artist whose primary interest has been the Land of Men, I didn’t always want to love him. I studied Scorsese in college – under Jeanine Basinger – through a traditional Film Studies lens: What are his interests? how does he use the tools? etcetera. I also studied the history of the Western with Richard Slotkin, whose central thesis was that America used the genre tropes of the Western to define and redefine itself as our attitudes toward violence and “others” have evolved. Had I not been taught how to read genre tropes and how to see Scorsese’s culture, his values, in his films I would not have wept with joy and awe throughout Killers of the Flower Moon. Had I just watched it as evidence of skilled craftsmanship, yes, I would’ve appreciated it, but I would not have felt affirmed. However, as text, as an American sorta-Western, Killers of the Flower Moon represents deep progress in the hearts and minds of white male filmmakers. I felt relief. The more mainstream filmmaking reflects a shift toward inclusivity and progress, the more I feel able to make my art.

So, initially my interest in film was from a critical, academic perspective. I still didn’t see myself as someone who could make films. A huge part of that had to do with not seeing many women directing. It happened, but it was rare, and felt inaccessible, maybe even nuts to stake my future on that dream. I was never a guy’s girl, and Hollywood seemed like a boy’s club. Screenwriting, however, looked like it let more women in. I’d been writing since I was a kid and I knew I loved to do it and was capable of putting myself on the page, so I was starting to let that dream in just a wee bit.

Crucially, during this time I started to work at the Wesleyan Alumni magazine and the Wesleyan Film Archives for my work-study jobs. I was learning about the alum who worked in film and TV, and of particular interest were the ones who weren’t wildly famous - the non-nepos. I was realizing that the business could provide a stable career even if you didn’t reach Michael Bay – our most commercial successful, non-nepo Wes alum? – status.

My senior year I signed up to write a screenplay for my thesis, and that was just it. I will never get over the feeling that I had then — and I still get it every time — which is this incredible thrill and awe that I get to just write a movie. A movie doesn’t exist, but then I get to describe it on the page and it exists. And this is a job? What? I realized that everything I loved, all the writing I'd done, was really to get to this place of using words to describe dramatic action.

CH: What was your thesis screenplay about? I’m curious what Liz W. Garcia the Filmmaker looked like in her most nascent, uncorrupted form.

LWG: Oh, it was so me. It was a coming-of-age dramedy about a sensitive, lonely teen girl in a small town whose path crosses with a feckless charmer on the run from the law. He seduces her and she thinks this is the answer to changing her life. We all know how this ends. This is the story I’ve been – unwittingly, as it typically goes – writing over and over and over: love is a temporary antidepressant, and it’s beautiful and all, but ultimately, only you and your art can save you.

CH: How much of that feels biographical to the person you were in college, but also the person you’ve become today? Why do you think you keep returning to variations of this story?

LWG: Cole, have you thought of being a therapist? Okay, let’s do this. Yes, this struggle between romantic love and self-healing has carried over into my adult art and adult life. See: The Lifeguard and One Percent More Humid. I think in some ways it’s a literal story. I’m, let’s say, serotonin-deficient, so I’ve always been on the hunt for deliverance from melancholy - and romantic love has been one such vehicle. But I think I return to this subject because it’s also about my writing, about my life. The cycle of popping my head out of the cave to be part of the world and have relationships, then feeling it all deeply, then having to heal by retreating and writing. So, when I tell the story of love, heartbreak and healing, it’s also a story about me just being me in this world.

CH: What I find so lovely about this answer is how your stories don’t just allow you to explore the world around you and maybe help others understand their own places in it. They seem to provide you your own language for doing just that, too. It’s a feeling I understand all too well.

LWG: Oh, absolutely! The unconscious finds its ways to express what’s churning in your brain, and it’s typically not direct and literal. We’re lucky if we understand the metaphor in our work. Sometimes I do, and sometimes I don’t. As I said, my mom is a painter, and something she’s said to me many times is “The work understands you before you understand yourself.” Sometimes I look back on my work and recognize “Oh, this was like a warning from myself to myself. Or this was advice I was trying to give myself and I didn’t even realize at the time.”

CH: I want to go back to Manohla Dargis’s piece about women loving film. Cinema history has its exceptions, but, for the vast majority of it, films haven’t told from the female gaze. That began to rapidly evolve in the Nineties, when you, like me, would’ve been discovering a deeper understanding of cinema. What was your relationship to the female filmmakers coming out at the time? Another way to put this is: you spent this time at Wesleyan honing a critical eye for cinema, but where were you turning for inspiration as a nascent female filmmaker?

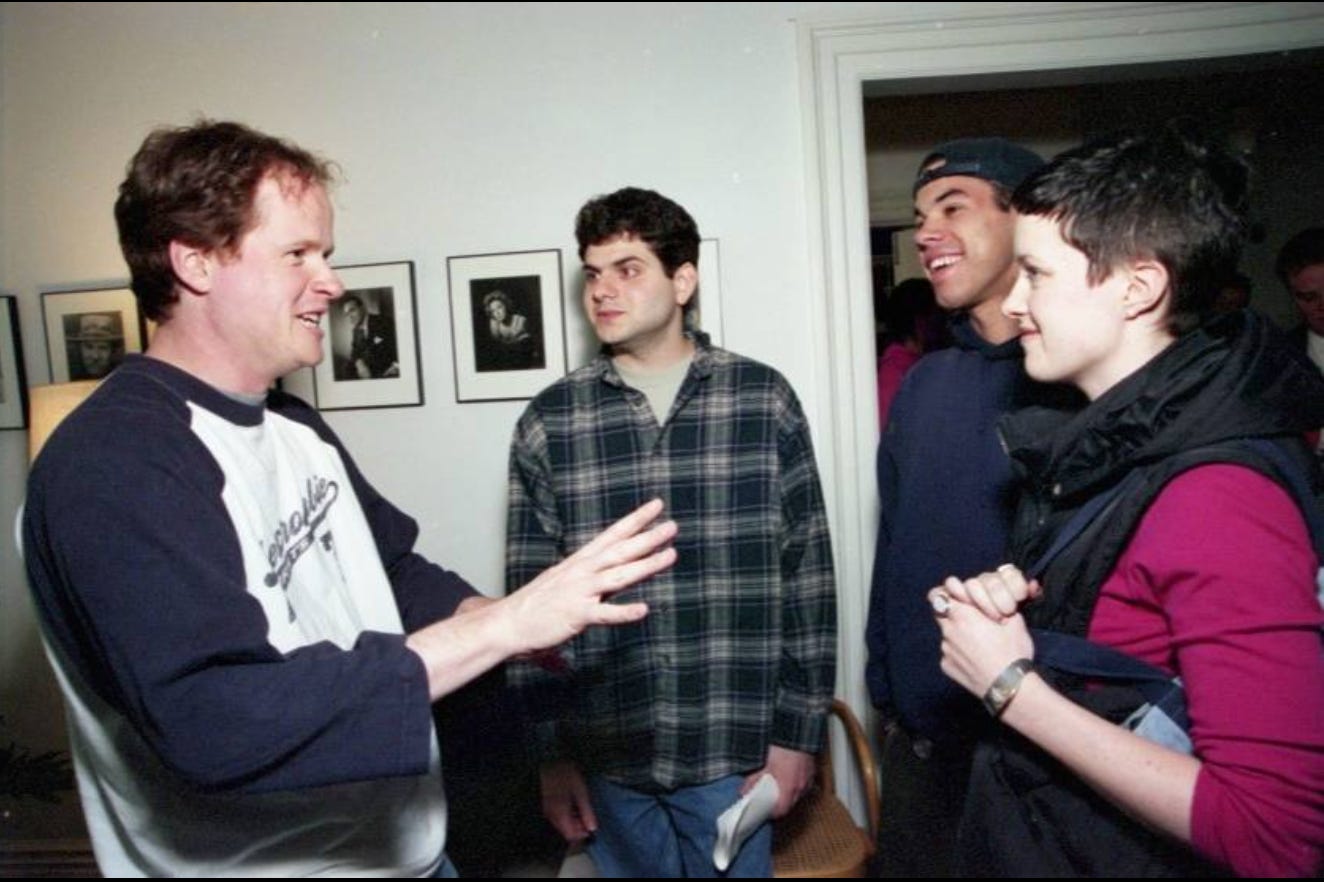

LWG: Okay, there was not a buffet of available role models after which to fashion my career, but there were a key few. I worshipped Joss Whedon and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer”. He is a Wesleyan grad and was making “Buffy”, this funny, feminist, queer, campy, passionate show that I saw myself in. I got to know him, and my friend was his assistant, so the dream of creating in TV and movies felt adjacent to me in some way. I also was watching the Nineties female indie directors like Nancy Savoca, Cheryl Dunye, Kimberley Pierce, Allison Anders. I knew “My So-Called Life” had been created by Winnie Holtzman. What I couldn't find in film and TV, I found in novels and poetry, and saw myself in Laurie Moore, Marge Piercey, Susan Minot. Miguel Arteta and Mike White came back to campus to show Chuck and Buck, and they didn’t seem like untouchable, fancy people. They seemed rumpled and poor, and that was helpful to see! Also, Jeanine Basinger, the founder of the Wesleyan Film Department, had a pretty inspiring origin story herself. She grew up in South Dakota in the Forties and as a kid was an usher at the local movie theater. She fell completely in love with movies, and taught herself everything she now knows about American cinema, which is more than any person alive other than Scorsese - which is why they’re friends. That’s a woman with grit with a capital G, and that filled my sails for sure.

CH: Earlier, you described how it can “feel fucking foolish to go down that same path with your career, just gunning for that thing that just doesn’t even notice you” about women and film. You also suggested screenwriting seemed to offer you enough of a potential way into the business, as a woman, to let you dream a bit. You will not be surprised to hear this, but for me, as a white cishet man, I never once questioned there was a place for me in Hollywood or that I could just show up and, a few years later, have a film made or a show on the air. Knowing what you knew, knowing you were always going to be vying for a piece of a pie I or someone who looked like me was just going to swoop in and eat most of instead – knowing all that – what do you think it was about you that lead to you saying, “Yeah, fuck it, let’s go kick Hollywood’s ass” instead of just pursuing a career that had a significantly lower chance of driving you to financial ruin and/or suicide?