Q&A: Writer Attica Locke on Risking It All for Her Art

The best-selling author and 'From Scratch' creator/showrunner gambled everything she had on herself...and it worked

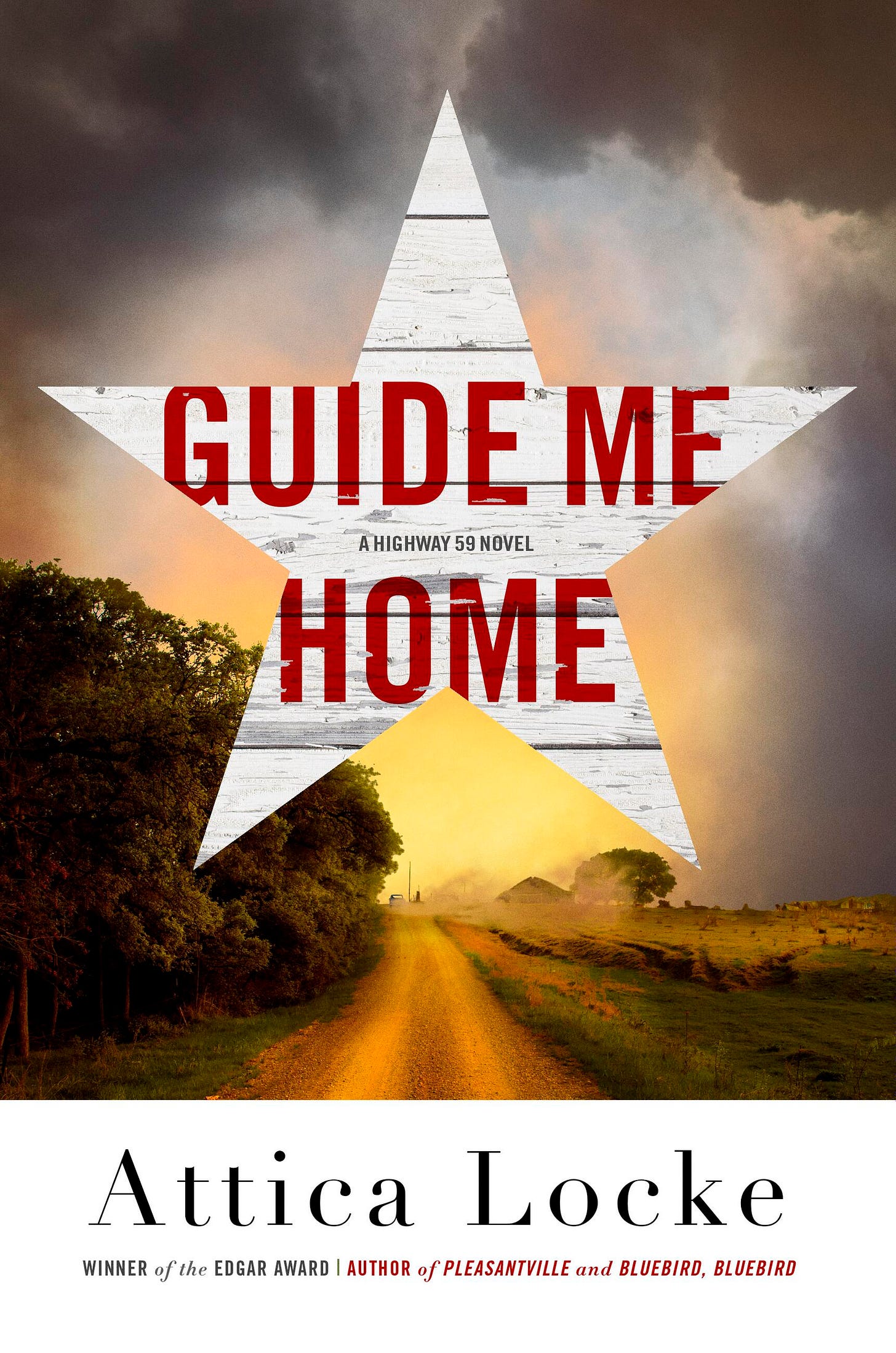

When Hollywood’s development system broke Attica Locke, she decided to do the unimaginable. What she risked could’ve cost her everything she had worked so for, but it was worth it because it helped her rediscover her real voice as a storyteller. First as the New York Times best-selling author of several crime novels — including Heaven, My Home, The Cutting Season, and Black Water Rising — and then, later, as a screenwriter upon her return to the world of film and TV (you’ll know her work from “Empire”, “When They See Us”, and “Little Fires Everywhere”). In 2022, she created and showran the series “From Scratch” — which was adapted from her sister Tembi Locke’s memoir — and, this week, her latest book hits shelves, Guide Me Home, which marks the third and final entry in her critically acclaimed Highway 59 series.

In short, Attica keeps herself busy.

This artist-on-artist conversation might prove confronting at times for some readers (good) and terrifying at others (I gasped at one point), but mostly I hope it inspires the shit out of you to never lose sight of who you are as an artist. Like me, or vice versa, Attica had to leave Hollywood to recover and hone her real voice after the film/TV industry had confused it. I wouldn’t recommend how she went about this — what she gambled is unimaginable to me — but, good god, it paid off in spades for her career and life, as you’ll see. You might even want to make some dramatic creative course corrections of your own as a result of what you read here.

COLE HADDON: Naming a character can cause paralysis in many writers. You so desperately want to get it right because of how it helps to define a character, for better or worse. I can’t help but start this conversation by drawing attention to your own name. Can you talk about its origins and how, if at all, it’s helped to define you?

ATTICA LOCKE: I was named after the uprising at Attica Prison in upstate New York in 1971. Even though I was born three years after the events of what at the time became one of the most violent massacres in American history, my mother felt strongly about what the inmates had been trying to accomplish by taking over the prison - the right to shower, to work for a decent wage, to read in their own language, to pray. She wanted to impart to me the idea that there is a basic level of humanity that we are never meant to go below in how we treat other human beings, no matter who they are. I have carried that message with me my entire life. As well as the power of the word "no”, the power of resistance.

CH: There are two aspects of your answer I want to interrogate a bit more. The first regards the basic level of humanity we must afford others, regardless of who they are. This is a powerful level of consciousness in general – of compassion, I’d say – so how does that express itself in your work if at all? I mean, in the kinds of characters you pursue or don’t pursue.

AL: I am hard-wired for compassion. Whether because of these early lessons I received or because compassion was often modeled for me as a child, or because I just constitutionally bend toward other people’s pain, their struggles. In my writing life, I hope this has shown up in the form of “villain” characters—or characters who are wildly different from me in terms of their beliefs, political persuasion, tolerance for people who are different from them—that are three-dimensional and not arch.

In a society that is increasingly investigating the ways in which trauma defines people, I, too, am often looking for the “wound” behind bad behavior when I write “bad guy” or “girl” characters. I am always trying to understand the psychological impulse behind people who are cruel or violent or even racist. To be clear, I do not think trauma creates or excuses racism – or cruelty or violence – but I do believe that destructive psychological belief systems lead to internal feelings that lead to racism. I have long held a theory that white folks who have a sense that the stories and myths they’ve been fed about their intrinsic greatness and prowess is a lie—that they did not, in fact, create this country on their own, but rather did so on the backs of Black bodies. Black bodies who built their homes, harvested their food, buttressed their economies, raised and fed their children. When that knowledge pierces the surface of the conscious mind, I think there are white folks feel robbed of something. Robbed of a belief about themselves as special. Better. I have also maintained that envy undergirds a great deal of racism. Because not only did you not build this nation on your own, Black folks have built all kinds of things with nothing. We had a boot on our neck for 400 years, and we still invented jazz. We are an extraordinary people. And I think that makes some white people feel desperately uncomfortable.

CH: I couldn’t agree more. I think white Americans – and I do this is a problem for most white people, which is why I speak so broadly here – but I think white people have an identity problem in the States. They’ve been fed a mythology for so long, whether it’s about their place in the pecking order or America being a country blessed by the Christian god or the rugged individual or how anybody – but really only white people – can transcend their origins and become president if they work hard enough. Or, as you’re saying, that America was built by them rather than significantly by Black people and, oh yeah, a bunch of other non-Europeans who were here to begin with or arrived from Mexico and the Caribbean and Asia. If that identity is threatened in any way, a startling percentage of these white folks – certainly compared to other countries I’ve lived in – choose violence and, very often, organized violence. What we’re seeing played out in the media, this anti-woke rhetoric, might have some basis in reality – there are certainly many people on the Left who worry things have gone too far – but the heart of it, what’s really irked these white people, is they’re being asked to tolerate a world where they’re not the center of it anymore.

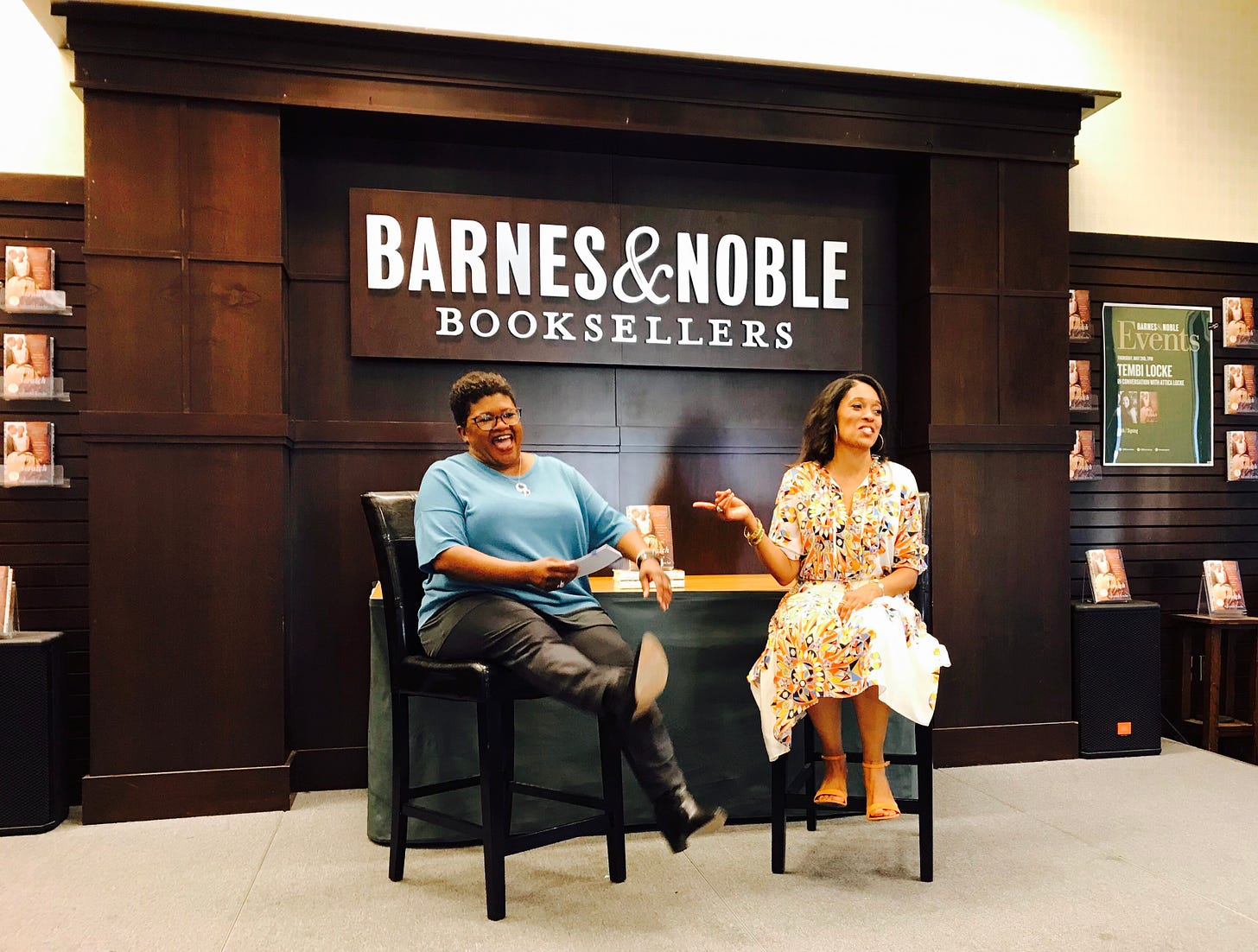

AL: Which is part of why art is so important. My sister, Tembi, has often said that Critical Race Theory is art. Not just books, but TV and movies, as well. There’s a hope that through art you can if not teach people history, at least get them to consider other people’s humanity of point of view.

CH: Have you found there are limits to compassion in your work and maybe even life? I think one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century is how it has diminished my compassion for the cruel. In their dehumanization of others, I can’t help but dehumanize them. I’ve struggled with how this has materialized in my work and, even when I think I find the right balance, it’s impossible not to feel like my work is more compassionate than I feel most days.

AL: Now, after all that stuff I just said about compassion and being hard-wired to consider other people’s pain and points of view, I have a hard time with Donald Trump. And I could not hate Greg Abbott, governor of Texas, more. They are both cruel and cynical men. For about half a second after I read Mary Trump’s book about her uncle and how Trump’s daddy treated him like shit, I felt bad for him. But I can feel bad for Trump and need his ass to stay the hell away from the Office of the President at the same time. I’m sorry all that happened to you, but you can still fuck all the way off.

CH: [Laughs] Agreed. I think, as a storyteller, one of the things I find most startling about what’s happened in the States is that reality now seems to defy some of the core rules of strong storytelling. People don’t say what they really mean, for example. Another would be that a character’s worst qualities shouldn’t be surface – nobody moves through the world saying, “I’m a villain!” But American society is increasingly that arch, a word you used a moment ago. It often makes it difficult to write characters who feel true because truth is now too absurd for fiction – even satire.

AL: I made a social media post recently about how the frenetic pace of social media scrolling and TikTok in particular feel more like real life these days—not to mention the surreality of communicating in gifs and memes—than traditional narratives. And of course, I wrote that on social media and I probably watch TikToks every day, in part because I am seeking art—and I do think TikToks are an art form—that mirrors how I feel in our current moment of history, which is partly driven by the chaos of social media. It’s like a snake eating its tail.

CH: I’ve found that anxiety, the “frenetic pace of social media” as you describe it, showing up in my work. How does your creative muscle react to it?

AL: It hasn’t shown up in my work yet, but I once dreamed in TikToks and it scared the crap out of me.

CH: [Laughs] It would me, too. So, let’s also talk about the concept of resistance in your work, which was the other follow-up I had about your name. I’m of the mind, as I expect you are, that all art is political, even when it doesn’t intend to be. How have you developed your tools to honor your name and the lessons that come with it while still entertaining your audience?

AL: One of the movies that has had the biggest impact on me as a writer was A Soldier’s Story, written by Charles Fuller who adapted it from his stage play and directed by Norman Jewison. I was ten when the movie came out in 1984, which is right around the time of the ubiquity of early cable TV. Because it played on cable a lot and I loved — loved — this movie, I watched it all the time. So, from the age of ten until I was into high school, I’d probably seen that movie fifty times. It is a master class on how to tell a story that is steeped in political philosophy while telling a damn good story. I think some of this approach got into my brain by osmosis and repeated viewing at a tender age. And, hell, maybe this is even part of the reason I became a crime writer. The movie – and it won’t give anything away because it happens in the first few minutes of the story – opens with a murder. And a crime story will keep you honest because the audience, such a reader, won’t accept a lot of pontificating on issues if you don’t keep the story moving along. One way to avoid being didactic—that the movie does, too—is to subvert political or polemical expectations. In terms of the story of Black and white race relations in America, in your story, every Black person can’t be an angel, and every white person can’t be a devil. This is also true to life, which is full of people doing unexpected things. As a writer, I try to always remember the element of life and lean into it.

CH: What I’d love to do next is get a better understanding of your creative journey. Journeys are never straight lines. Mine certainly wasn’t. So, could you take me back to 1999 as you headed to the Sundance Feature Filmmakers Lab? Who did you think you were going to be as an artist at that point? What was your vision of how your future was going to play out?

AL: I started out believing I was going to be a movie director. That’s what I thought Sundance was leading me toward. It was the most “auteur” medium and form of expression I could imagine. I wanted to tell stories in my voice, and this was the medium through which I thought I could do that. What’s so funny is that — having worked in production now — I have come to dismiss the idea that any TV series or movie is ever one “auteur’s” vision. It is a deeply collaborative art, even with a helming voice. The work is made with many hands and by many minds.

CH: So, cinema was going to be your route to expression as an artist. How did reality react to that ambition? Journeys, as I said, are never straight lines.

AL: Basically, someone told me “no.” I had a deal to make my first film twenty-plus years ago, and the studio pulled the plug. They framed it as an issue of the world — literally, since they were an indie studio hoping to fund the film with foreign financing — not caring about Black American life, particularly rural Black American life.

My first film was based on a script that held the bones of the novel that became Bluebird, Bluebird. For decades, I kind of shut down my real voice and became a screenwriter for hire. Until I hit an existential wall. What was the point? None of what I wrote was getting made. And I was often writing for people who don’t fundamentally love to read. I had an epiphany one day — I could write a book. I wouldn’t need a budget or a line producer or a green light. I only needed a computer and the courage to do it - and the money I borrowed on my house to take time off to write the book, a house I could only have bought because of my work as a screenwriter...just to keep it real real.

CH: So, a lot to unpack here. First, I so rarely hear someone describe producers and execs as people “who don’t fundamentally love to read,” but it’s difficult not to feel that way. I mean, look at the trend over the past eighteen or so months toward setting up short stories, most of which were unpublished and will always remain so, as IP. I was told over and over by industry types, “People don’t want to read novels or scripts. They’ll read a ten- to fifteen-page short story, though.” It’s such an infuriating reality to face since anyone with any understanding of the business knows it all begins with scripts, which require passionate readers to bring to life.

AL: I should clarify or at least offer the observation that I also don’t love to read when it’s for “work”. I only ever want to read for pleasure. I know many execs who are readers, who love books. But don’t ever have time to read what they want because they have so many scripts – and sometimes books – to read that they’re often not reading for pleasure.

CH: But I do think it’s a startling difference from, say, publishing, another medium that we’ve both worked in that relies heavily on the value of the written word. Editors, which are a fairly close analogue for producers, don’t get to skim a manuscript they’re trying to bring to market or “only read dialogue” as I’m often told is all you can count on agents and execs to read. I suppose what we might really be doing is condemning the propensity for quantity over quality in Hollywood.

AL: Yes, and a culture where slowing down is discouraged.

CH: How did your mental health – or creative health, I could also say – improve once you began to write fiction, too? What I really mean is, once you emancipated yourself from the Hollywood hamster wheel.