Q&A: Screenwriter Shawn Ryan on His Evolution from Rebel to Establishment

The creator of 'The Shield' and 'The Night Agent' looks back on his long career and what he's learned about TV storytelling - and himself - along the way

Shawn Ryan is one of those TV writers I find it hard not to refer to as a titan of our craft. After gifting “The Shield” the world in 2002, a landmark series about corrupt L.A. cops that many hail as the start of TV’s golden age, he went on to create or co-create and/or showrun a train of other hit series including “The Unit”, “Timeless”, and “S.W.A.T.”. In doing so, the Emmy-nominated screenwriter has had to shift between working for network, cable, and streamers with a gracefulness usually reserved for ballerinas, acrobats, and mutant superheroes. Most recently, he adapted “The Night Agent” from Matthew Quirk’s novel of the same name during the early days of Covid. He did it on spec, too. Netflix bought his passion project, and it’s since become one of its most-viewed series of all time and has been renewed for a second season. It’s one hell of a career, spanning a quarter-century now, and he and I are about to discuss how it all started and what he’s learned about television storytelling — and himself as a storyteller — along the way.

For screenwriters, I would pay special attention to Shawn’s perspective on writing for network versus cable or streaming, his reflections on the writer he was on “The Shield” as opposed to the writer he is today, and how being a high-level showrunner impacted his writing.

COLE HADDON: I’m curious what kind of writer you are, Shawn. Is it a compulsion for you, a job you happen to be great at and enjoy, or is it somewhere in between? What I’m getting at is, do you wake up every day with a terrible itch to sit down and put metaphorical pen to paper — you know, where you can’t even turn it off when you’re on vacation — or is it something that occupies a very specific part of your life and you can behave like a normal human being the rest of the time?

SHAWN RYAN: I would say that I’m the kind of writer who constantly thinks about stories and things to write, loves to break stories, but dreads having to actually write it - but then is thrilled and proud when I’ve finished writing something. The blank page is a terrifying thing and it always takes me much longer to write the first fifteen pages of a TV script than it takes to write the last forty. Once I have momentum, I’m okay, but, damn, getting started is hard. Eventually, by the last twenty percent of the script, I find myself enjoying it. What I really love to do, though, is rewrite. When I have a hard copy of a script and a pen, I love to just sit in a chair and make pen changes. I think that’s where I do my best writing.

CH: A physical script and a pen ready to make it up are my happy place, too. I often marvel at the fact that I put so much work into that first draft, but there ends up being more red ink on the pages than the original black.

SR: I actually was a bit traumatized early in my career when my boss John Wirth would use red pens to mark up and note my scripts - usually in major ways as I was a staff writer. When I became a showrunner, I started using blue pens to mark up and note scripts. Seemed nicer and less “bloody”.

CH: Oh god, I don’t think I could take someone else using a red pen on my work. Just brutal. So, you’ve been doing this for more than two decades. What was your Achilles Heel as a writer in 2003 compared to 2023 and vice versa? One always thinks writers only grow better with practice and experience, but I think everything from success to personal traumas causes us to evolve in both directions.

SR: I think I’ve become a deeper writer since 2003. I think I understand more about life now and can write about it in more honest ways. I think my faults had more to do with me as a person than me as a writer. I just look at the world differently now and that causes me to write differently - and hopefully better, or at least laterally in a different way. I think I was more plot-oriented earlier in my career, and I let character drive plot more now.

CH: I’m going to come back to this subject in a moment, your evolution as a writer, after we get to “The Night Agent”. But first, let’s take a step backward. Tell me about who you were as a kid. What was life like in Rockford, Illinois? Are they good memories for you?

SR: I was a child of contradictions. In some ways, I had a very successful childhood. I was a good athlete who played all kinds of sports, acted in plays in middle school and high school, did well academically - though was too interested in other things to ever maximize my academics. I was popular enough I guess, but not too popular. Despite all this, I was a late bloomer, so I was usually the shortest kid in my class, including girls. So that was weird and messed with my head until my junior year when I grew from 5’2” to 5’11” in five months.

CH: Jesus Christ. I think someone sprinkled super-soldier serum onto your Wheaties.

SR: Except then I was the skinniest kid anyone had ever seen. But I was generally a happy kid who wanted to be involved in everything, always wanted to be busy, to be entertained, and, of course, I watched way too much TV as a kid. My parents didn’t like how much TV I watched.

CH: What were you watching?

SR: Interestingly, mostly the classic sitcoms of the seventies and eighties. “M*A*S*H”, “All In the Family”, “Mary Tyler Moore Show”, “One Day at a Time”, “Happy Days”, “Laverne & Shirley”, “Cheers”, “Taxi”. I preferred sitcoms to dramas growing up.

CH: Your first produced credit is actually on an animated sitcom, “Life with Louie”. Is there another timeline out there that Shawn Ryan is a successful sitcom creator/showrunner rather than one working in hour-long drama?

SR: To correct you, my actual first produced credit is a “Story By” credit on the show “My Two Days”, which came out of a two week internship I did on the show after I won a playwrighting award. I had a two-line pitch that Bob Myer – the showrunner then – liked and fleshed out on his own right in front of me and handed off to two staff writers to write.

I had won a comedy playwriting award, so when I came to L.A., I thought I was supposed to be a comedy writer. I gave it a real shot, but then also started writing dramas. I had meetings on shows like “Boy Meets World” and “Sweet Valley High”, but couldn’t land any of them. I wrote a freelance episode of “Sparks” on UPN, but they rejected it and didn’t film it. I did land a freelance on “Life with Louie”, and did well enough that they gave me two more scripts. That show was really good actually, and I got the nicest call from Louie Anderson after I wrote the first one, and I was a real nobody, and he was really encouraging and supportive. So, I guess I could have been a mediocre — or even failed — comedy writer. Ultimately, I got staffed first on a drama when I landed on “Nash Bridges”. Interestingly, they hired me off a comedy script I wrote - a spec of “Larry Sanders Show”.

CH: You mentioned your parents didn’t approve of all your TV watching. Did you make sense to them as a kid?

SR: Fortunately, I was productive in life when I wasn’t watching TV, so my parents weren’t too tough on me. My parents were great. I had a good childhood. They got me. They were very supportive of any activity/sport I wanted to try. And I wanted to try everything. I was a curious, adventurous kid.

CH: Let’s dig more into that. Your childhood was good, as you just said. Your parents, supportive. You sound like you had very typical growing pains in high school, though maybe literally given how fast you grew. Sounds like a great bedrock to build a healthy adult life on. But personal experience with artists suggests adversity entered the picture at some point. Was it college or later that you stopped yourself and said, “What the fuck am I doing, is this really the future I’m going to choose for myself?”

SR: I was a hockey goalie from the age of four, and one of the first things you learn is that you can’t let failure — allowing a goal — to prevent you from doing your best going forward. So yes, I had very typical struggles growing up – issues with friends, disappointing my parents or myself, crushes who weren’t interested in me, a lot of goals let in on the hockey rink, but I always had an ability to put them in the rearview mirror and move on to the next thing.

This kind of attitude worked for me for a long time, basically until I graduated college. But then my friends tended to go off to jobs or grad school, and I didn’t know what I was going to do. All I knew was I wanted to write for a living, but I didn’t know how to go about doing that. I applied to grad school for playwriting. Yale rejected me and I got into Southern Illinois, but I couldn’t really afford to go. I had a real crisis of confidence at that point. I had graduated from college, but I hadn’t really evolved emotionally out of college yet. I got a job writing ads at a radio station in Burlington, VT. I’d work there during the week and then go back down to my college — about forty-five minutes away — to hang with my friends who were still there. I knew I couldn’t live with not pursuing my dream, but with no connections and no internet to research possibilities, I was just stuck in Vermont, unsure what to do.

CH: What changed?

SR: Out of nowhere, a play I had written and produced in college my senior year won an award through Columbia Pictures Television - and all of a sudden I was being flown to L.A. to observe “My Two Days” for two weeks. I thought, “Well, they’re flying me here. But I’m not flying back. I’m just going to stay.”

And that’s what I did. I took that opportunity and figured I was going to give myself my twenties to try to make it as a writer. I only knew one person in L.A. when I moved here – Jay Karnes, who eventually played Dutch on “The Shield”. And I’d only known him for five months at that point when he played the lead in a play I wrote at a playwright’s retreat in Virginia.

So, yeah, I had some doubts about how wise it was to pursue a career as a writer, but that playwriting award was a godsend as it legitimatized my dream to myself and my parents and brought me to L.A.

CH: When I first moved to L.A. in 2005, I landed in Echo Park – the LAPD’s Rampart division. A few weeks after moving into a house on Coronado St., someone knocked on the door and, more or less, asked, “Can we shoot a TV series here? We just want to throw a grenade over the fence.” My response was, of course, hell yes. The landlord promptly said no. But that was “The Shield” they were shooting – which you just brought up – and I was disappointed because I was such a huge fan of the series. It’s been just over twenty years since it debuted, so I can’t help but wonder what you, today, after a quarter-century in this job, think about what you pulled off. It felt at the time, at least for me, that so much of the show didn’t give a shit about what else was happening on TV. It was just going to be its own thing on its own terms.

SR: Yeah, we just did our own thing and were too inexperienced — except for our producer/director Scott Brazil, who was the adult on the show — to know any better. We’d always ask ourselves, “What have you never seen on TV before?” We’d figure out there was a good reason why a lot of stuff hadn’t been on TV before, but for every nine things we rejected, we’d find one great original idea that just seemed so fresh and new. It was an exhilarating time. It was the kind of show I had to do when I was young before too many rules were ingrained in me - and we were lucky to be there at the inception of cable shows, before streaming when you could really take risks and be successful. I imagine it was what the film world in the seventies felt like. You knew you were part of a special time, you’d hope it would last forever, but deep down, you knew that it wouldn’t. I remain very proud of the show and what we are able to portray over seven seasons.

CH: Is there any temptation to return to the world, to the character of Vic Mackey in particular, especially in a TV environment where such sequel series are more possible than ever before?

SR: There’s always been a temptation because those times were so great and the work was so wonderful. So yeah, it’s intriguing. But then you have to ask yourself, “Am I mistaking nostalgia for an actually great idea to write about?” I’ve seen a number of shows rebooted or revisited later, and I can honestly say I’ve never seen one that returned at the level of quality as its previous heights. So, that makes me dubious.

SR (cont’d): I don’t think I ever want to close the door to revisiting “The Shield”, but the bar is so high for what would make me return to it that I think, as the years pass, it’s becoming increasingly doubtful. I’m so proud of how it ended, and I would never want to do anything that sullied that. So, the door is always open for the right idea to inspire me, but so far, I haven’t had the right idea yet and I’m not afraid of leaving the show where we left it in 2008. We were able to do crazy ass shit on “The Shield” at that time. It’s a different time now. I don’t know that an update would feel like the right thing at this time. I don’t know.

CH: I appreciate how longingly you just described this Wild West period of cable TV. I’ve never heard a writer describe self-awareness of the ephemerality of it, but I bet it heightened the experience in many ways. What was the adjustment like to the “real world” when you moved to network?

SR: To be honest, I had good experiences at networks after “The Shield”. A lot of the restrictions were self-imposed as I understood I was writing for a different audience and a different platform and the mischief we could get into on FX, I couldn’t get into on CBS. But I enjoyed that challenge and I loved writing shows – “The United”, “The Chicago Code” – that were geared for a wider audience. I often tell the story that back in the 2006-2008 era whenever anyone in L.A. found out who I was, all they wanted to talk about was “The Shield”. When I was back home in the Midwest and people found out who I was, all they wanted to talk about was “The Unit”. I loved that duality in my life. On a practical level, I had just as much freedom on “The Unit” at CBS as I had at FX. I just knew I was playing in a different sandbox.

CH: It’s a duality that has continued ever since, too, I think. Your work has vacillated regularly between network/cable and streamers, between what we in the industry commonly distinguish as commercial and prestige TV, but also, almost as often, blurring those lines for audiences. How do you view these labels? You just suggested restrictions you felt at network were initially self-imposed – which feels true, at least in some ways, from my experience – so I wonder if writers are creating their own limitations in your mind?

SR: I think they’re just labels, I don’t think they’re really reflective of the quality of the work. I think some broadcast shows are sneakily a lot better than a lot of “prestige” shows that have all the elements but feel empty. There’s something really challenging and rewarding about making twenty-two to twenty-four episodes a year of a show that a lot of people count on watching every week – and making sure the quality stays high enough that people want to keep watching.

Network restrictions often lead to really cool episodes. I think the flip side of this is that sometimes writers lean too much into the “freedom” of cable or streaming and they do things that don’t feel grounded or earned just because it’s cool to do something outrageous. It’s certainly harder to shock an audience now than when “The Shield” premiered. Sometimes I feel writers and shows are trying too hard now.

CH: Your career also entails a lot of seesawing between episode counts. Some series, such as “The Unit” or “S.W.A.T.”, are traditional runs – twenty-plus episodes per season. Most exist in that aughts transitional space, from network to cable, of ten to sixteen episodes per season, which includes “The Shield”. But TV, especially streamers, have increasingly shifted to seasons of six to eight episodes in length. Even half-hour shows. I’ve often wondered what that has done to audience loyalty, the ability to forge deep relationships with characters, when we don’t have longer runs – and what that does to a series’ chances for long-term success. You referenced a lot of TV series earlier that also flout the wisdom of this short-season trend. What do you think?

SR: I think it’s hurt audience loyalty. I’m not sure there’s any going back, but it used to be you only had to be without your favorite show for three to months a year. Now, it’s not unusual to wait eighteen to twenty-four months between seasons of your favorite show. I think, often the audience forgets and moves on. It’s unfortunate.

CH: We should talk about “The Night Agent”, your most recent TV series. Congratulations on its success - including its renewal for a second season. I recall reading a few months back that the series reignited your passion for writing or, at least, something to that effect. Can you talk more about that? For example, where had that passion gone and were you aware it was disappearing on you?

SR: As a showrunner on “S.W.A.T.” and “Timeless”, I had co-written the pilots for both shows, but hadn’t written any other episodes as I focused on co-running those shows. It had been a while since I had written something solo and, during the beginning of the pandemic, I found myself going back to basic principles and just thinking I should write something solo like I had done with “The Shield” pilot. Not develop and pitch it, but just write it. I wanted to write again, just for myself, just to please myself and prove I could still do it, and the pandemic gave me the time to try.

CH: You obviously succeeded.

SR: I enjoyed writing “The Night Agent” pilot so much, when it was picked up, I decided to write Episode 2 and co-write Episode 3, as well. It just reminded me of how and why I got into the business. I’ve always rewritten or polished all the scripts on my shows, but I loved throwing myself back into writing. I did the same thing for Season 2 where I wrote the first episode of that season - before the strike began.

CH: I wondered a moment ago if your passion for writing had been waning for any reason before “The Night Agent”.

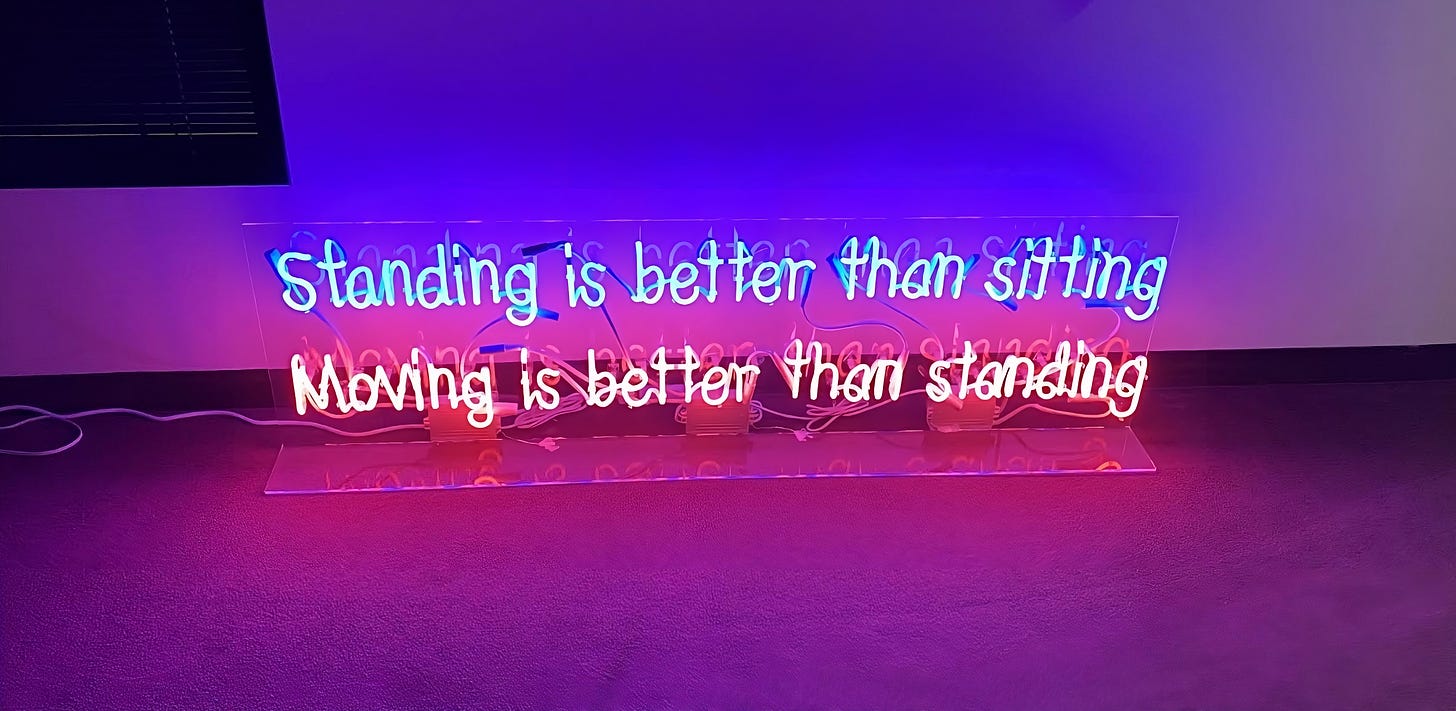

SR: I don’t think there was anything wrong with what I had been doing before. I hadn’t lost the passion for storytelling, but the time commitment to run a show — and sometimes two simultaneously — just made it easier to assign scripts to other writers on staff and then polish them afterward. I hadn’t lost my passion for writing, but felt I didn’t have the time to pursue it. The pandemic changed my thinking and made me decide to make the time to write more. I’m glad I did. Felt like going back to basics.

CH: I think the pandemic gave many of us a chance to hit pause, to rethink decisions we had made as artists. Not that the decisions were necessarily wrong, I don’t mean that. But that where we were, however we got there, had lacked perspective before Covid. Suddenly we were able to articulate — or maybe just recognize — what was missing for us.

SR: Yeah, I felt that way. There was that period where you really wondered, “Am I going to get this virus and is it going to kill me?” It focused me. It also isolated me from everyone else but my family. It was a clarifying event and it made me appreciate my life and my profession more.

CH: Did the pandemic reveal anything else about your work besides a desire to focus more on writing?

SR: I’m not sure. I don’t know as writers that we always understand intellectually how we might have changed or how our work might have changed. I just like the work I’ve done since the pandemic started. I don’t know if that’s random, or if it’s a function of the pandemic or not.

CH: I mentioned earlier that I wanted to return to the subject of your evolution as a writer, and your last answer makes this like the right place to do that. You previously described how you think you write in more honest ways now, which you attributed to understanding more about life – which means we’re talking as much about your evolution as a person, too. It’s a strange thing to be an artist who can track their maturation through their public work, right? As we “grow up”, as life happens to us — the really hard stuff more often than not — we become better at what we do. Except in our cases, there’s this record of who we are, in our work — in our work’s failings, our ideas, our naïveté — for all to see. I’ve sometimes looked back at what I wrote in the nineties and early aughts and not recognized myself at all, and sometimes I even wonder how I can get back to him despite how much I like the person I’ve become. What is your relationship like with your earlier work and have you spent much time reflecting on how you’ve “grown up” through your work?

SR: I found myself watching some “Shield” clips on YouTube the other day. I enjoyed them. I thought, “That was a pretty good show.” But other than that, I don’t dwell on my past work. I know that there were some useful youthful advantages I had earlier in my career. I had greater stamina. I could work — and make others work with me — past midnight every night. We could just grind and grind until we arrived at the best possible script. But that’s not a great way to maintain a marriage or to be a good father.

CH: Very true.

SR: I understand that I was the rebel when I made “The Shield” and that I’m the establishment now, and I’m cool with that. I think I can still do surprising, subversive work from my establishment perch. “The Shield” is work that I’ve done that’s pretty much in dried concrete now. No one can ever take it away from me, and I think it has and will stand the test of time - especially from beginning to end, which I think are connected in ways that most TV shows never are. I accepted a long time ago that I might not ever make a show as good as “The Shield” again and, if not, I’d be okay with that. I didn’t want “The Shield” to represent handcuffs to me. I wanted that success to give me the freedom to try whatever else I wanted to do. I’ve had that critical success once before. I don’t need to have it again. I’m okay just trying to please myself. And I enjoyed “The Night Agent” in the editing rooms just as much as I enjoyed “The Shield” in the editing rooms. Different shows, different goals, but same level of personal joy. That’s what I’m looking for.

CH: It’s a good pursuit.

SR: “The Shield” is a show I couldn’t write now. And “The Night Agent” is a show I couldn’t have written then. I needed to suffer the death of my father in order to write “The Night Agent”. I needed to be young and cocky to write “The Shield”. I think it’s a beautiful thing that at different times in your life, different events in your life can lead to very different projects in your life. I’m blessed to be a writer and to still be working.”

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

This was one hell of an interview, Cole. THE SHIELD was such a massive influence on my desire to write for television.