Q&A with Nicholas Meyer: The Filmmaker and Author Discusses His Life and Legacy

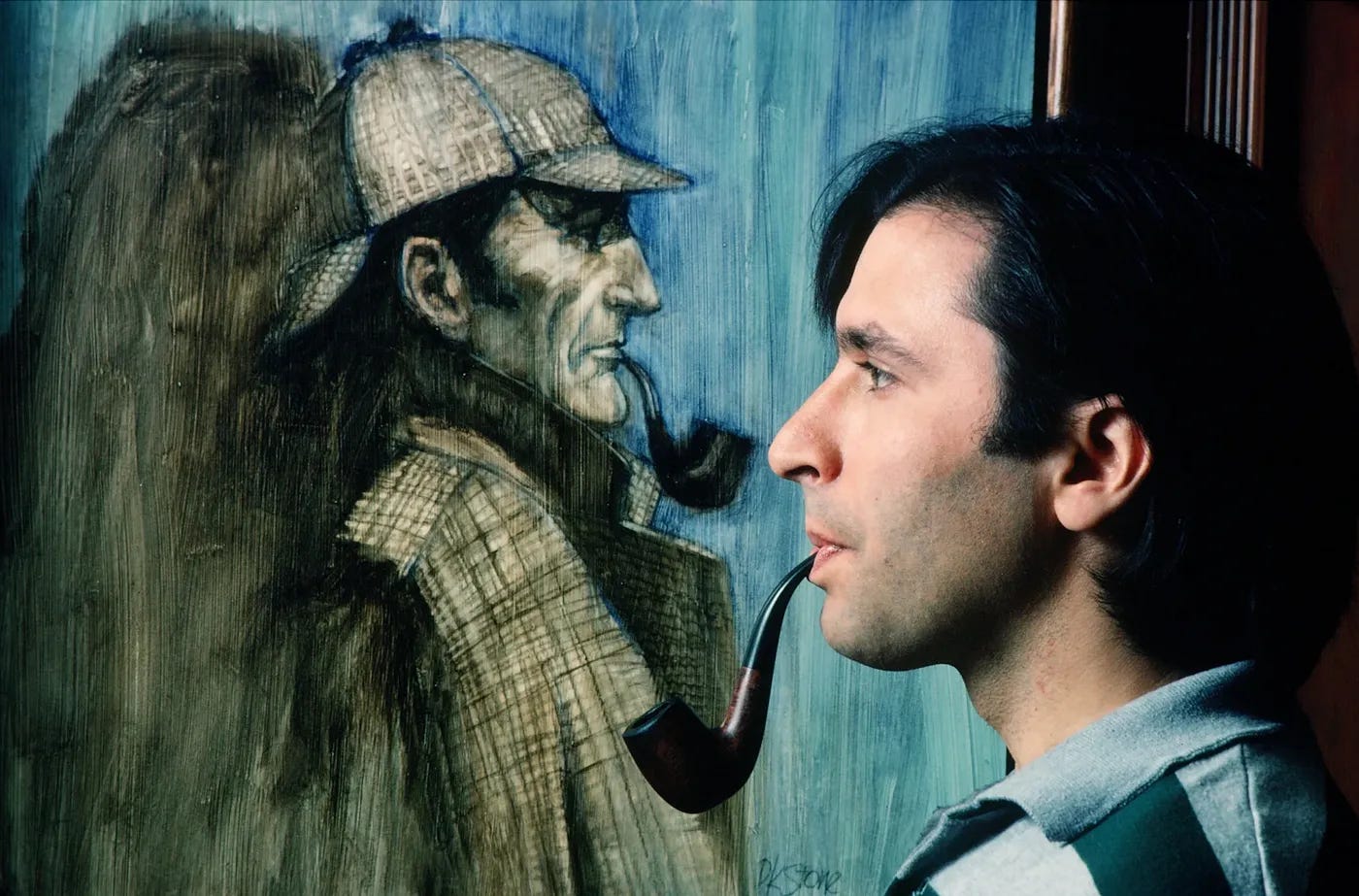

The storyteller who saved both STAR TREK and Sherlock Holmes from extinction talks the origins of his creative life, three key artworks in his early oeuvre, and his legacy.

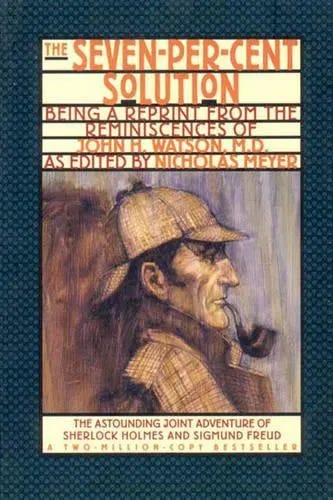

I don’t remember when I became aware that Nicholas Meyer existed, but I was very conscious of his work long before I knew his actual name. My gateway drug into his decades-long oeuvre that spans film, television, and books both fiction and non-fiction was, as it has been for many, STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF KHAN (1982) — which he both wrote and directed, saving the franchise from likely extinction and redefining its relevancy for years to come. By this point, he had already done the same for Sherlock Holmes with his novel THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION (1974) and its adaptation for the big screen (1976), both of which fundamentally altered how the character would be depicted for decades to come by placing Holmes rather than the mystery at the heart of the story.

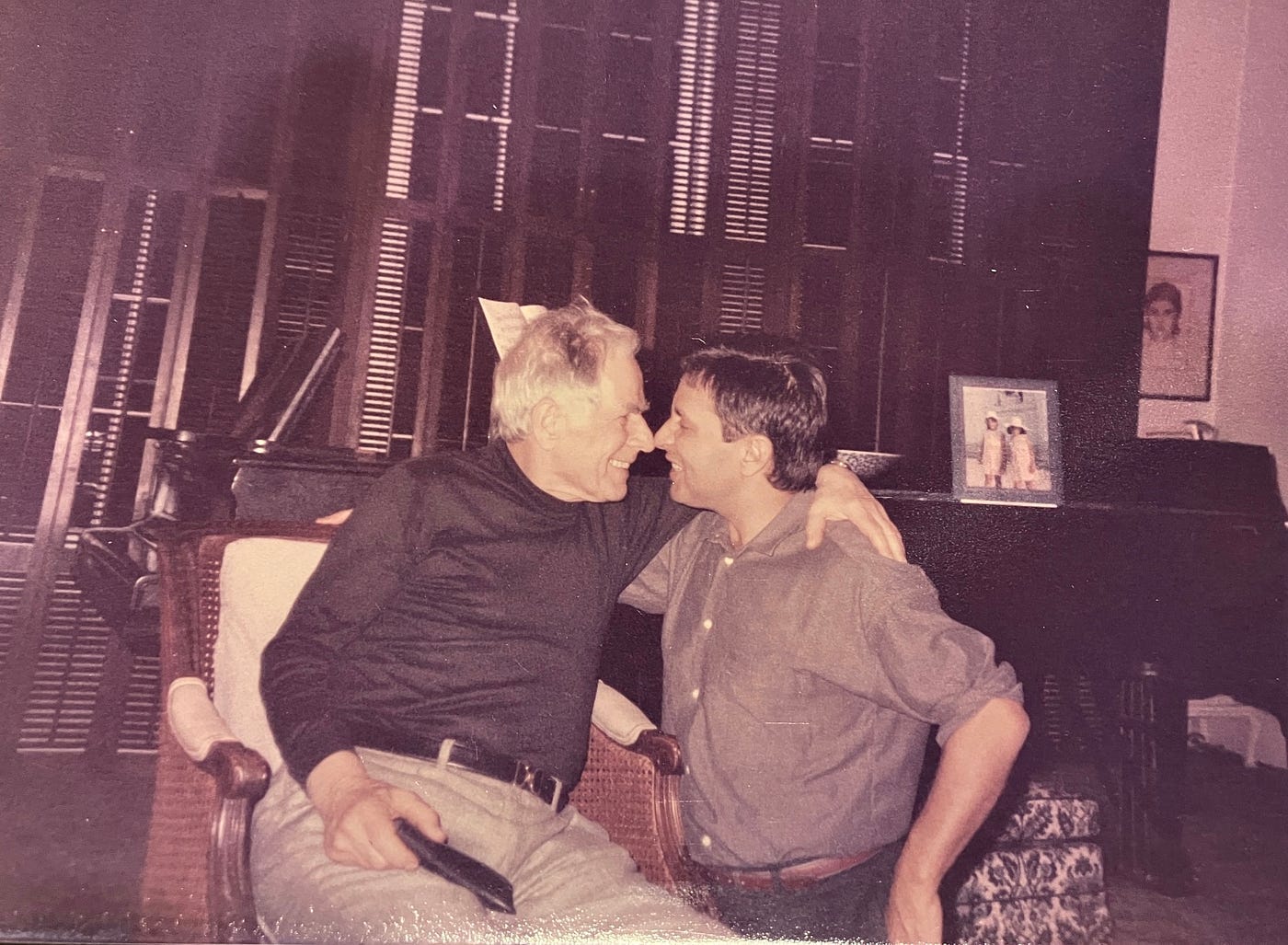

Years later, after my love affair with Nick’s work had grown far more robust, I was fortunate enough to become friends with him. Since then, we’ve broken bread together on many occasions, giving me an opportunity to hear many of his stories (he’s a world-class raconteur). When I began this artist interview series, I immediately reached out to him with the hopes that he would allow me to digger deeper into his life than we had previously gone, giving me the chance to better understand how he became the storyteller who left such an indelible mark on me. To do this, I would focus on three key pieces of art from him that I believed were deeply interconnected: his novel THE SEVEN-PER-CENT-SOLUTION and the films TIME AFTER TIME (1979) and STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF KHAN. This is that conversation…

COLE HADDON: I’ve been lucky enough to have many conversations with you over the past eight years, which is about how long we’ve known each other now, I think. Some of my favorite stories you’ve told me — and there have been many, I’ve sung your praises as a raconteur elsewhere — I think my favorites have been are about your childhood. You get very passionate recollecting the music that was played for you and the films that captured your imagination. I wonder, how would you describe the role of arts in your childhood and, I suppose, the formation of your identity?

NICHOLAS MEYER: I was born four months after the end of World War II in New York City, a magical time and place for a middle-class family. America was the best, the strongest, the good guy, the hero in the white hat who saved the world, etcetera, and New York City was the center of the universe. It was like Disneyland, except it wasn’t plastic. It was all real, and a middle-class family could, without difficulty, seize every advantage the place had to offer. Opera, ballet, theatre, museums, schools were affordable. Plus, every kind of extracurricular activity — and Manhattan was a safe place for a kid to run around in.

My parents were non-observant Jews. Neither my father nor I were bar mitzvah, and I grew up without the religion gene. But I did soak up every play, movie, opera, musical, ballet, concert they took me to. If childhood impressions are the most potent and lasting, I was bombarded with wonderful things at what is generally termed an “impressionable” age. Small wonder all that stuff never left me. I’ve added to my passions over a lifetime, but I don’t think I’ve ever discarded many.

CH: Your mother [Elly] was a concert pianist and your father [Bernard] was a psychoanalyst, which I find such an interesting pairing because both, in their own manners, worked in fields interested in understanding or illuminating the human condition. That said, most people would draw a sharp distinction between the arts and psychiatry. Did the contrast work well for them in their marriage, and how do you think it affected you and how you understood the world as you grew up?

NM: Your question slightly oversimplifies my parents’ relations. In fact, music was the glue that brought them together. My father was himself an excellent pianist — the best sight-reader I ever saw, better than my mom. They met in Boston, where she grew up, where he was ushering at a concert. I believe she took an interest in his professional life and work, but it was music itself which largely and initially bonded them. The marriage itself was…like many marriages, complicated. Women in the post-WWII era, I think, were confused about the many roles they were now expected to fill — wife, mother, some job or profession. [My mom] was not, as it happened — in my experience, at any rate — an especially maternal figure. My father was the much more involved parent.

CH: I certainly didn’t grasp the extent of your father’s passion for music. Do you think that early immersion in it, in music — the fact that so much of your formative years is, it sounds like, significantly defined by it — do you think it shaped you at all as a storyteller and, if so, how?

It looks like I can’t intelligently answer this question…beyond the inarguable fact that, loving stories of all kinds, I grew up to tell stories — of all kinds.

NM: I recently gave a talk (Jan. 14th 2023) at the House of Commons on the subject of influences. That is where the Sherlock Holmes Society of London holds their January black tie dinner. My talk centered on the fact that influences are hard to identify or pin down. Lots of times we are influenced by things, people, sights, art, experiences, that don’t even register at the time. Many of these are childhood experiences. Some are memorable or traumatic as they occur. Others remain dormant, but assert themselves in our behavior or work in ways about which we remain only obscurely aware — if at all!

NM (cont’d): It is additionally difficult to answer this question because I am not myself very analytical person — and this despite having been “analyzed”. I can only assume that so much exposure to art — art of all kinds — as a very young person, made a lasting impression on me at that “impressionable” age. But precisely what those influences were and how they manifested themselves in my later life and work is more difficult to pinpoint.

Does a fondness, a passion for music, for theatre, for opera, ballet and film translate into anything more than a love for all those forms of art? Does it in some way determine what my art or character becomes? Can we detect “themes” or preoccupations in all that stuff? To take an exalted example, what can we infer about Shakespeare from his plays? Anything? Beyond an enthusiastic affection for an expertise in the stage? We he gay? Straight? A warmonger? A peacenik? Hard — if not impossible — to say. Okay, he thought all the world’s a stage, but beyond that? It looks like I can’t intelligently answer this question. Beyond the inarguable fact that, loving stories of all kinds, I grew up to tell stories — of all kinds.

CH: Your father being a psychoanalyst, that must have bled into how he approached his marriage, but, more importantly, his parenting. What impression — to use a word you’ve returned to a couple times — what impression did his career make on you as a person and storyteller? I ask because psychoanalysis obviously plays a significant part in your debut novel, THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION. (For readers, Dr. Watson compels Sherlock Holmes into treatment with the father of psychoanalysis himself, Sigmund Freud, in the first of what I like to call your mashups of fiction and history.)

After we went to see the AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS, I had a religious experience and longed to make my own film…and I asked my father, owner of a wind-up 8mm Revere movie camera, to help me.

NM: My father was the more involved parent and, as an adult, I came to understand that especially at the beginning, his involvement with psychoanalysis produced some peculiar results. As a kid, I was prone to losing things and I was bewildered when my father persisted in asking, “Why do you think you did that?”

CH: Interesting.

NM: I had not the foggiest notion of what he was getting at, and I think — without having been able to articulate this — that I would have understood a simple scolding much better. Later, I think he outgrew this sort of thing.

My father was a wonderful narrator, a storyteller. At dinner, when I was little more than five, he’d have me wide-eyed at tales of George Washington and the American Revolution — I thought this the greatest story ever — and gaga when I listened to him describe the subsequent revolution in France where they chopped off the king’s head. And the Queen’s!

My father, as you may have inferred by now, was an artist manqué. He could have been a pianist, a composer, a writer — he was the author of two full length biographies, one of Joseph Conrad, the other of Harry Houdini. After we went to see the [producer] Mike Todd film of AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS, I had a religious experience and longed to make my own film — of course it had to be of AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS — and I asked my father, owner of a wind-up 8mm Revere movie camera, to help me. My father entered into this — five year! — project with a suspicious enthusiasm. However fraught our relations were during the trying times of my adolescence and my mother’s fatal illness, work on the movie continued, on weekends, school holidays and summer vacations. It was definitely a bonding experience, which I treasure always and which I think afforded him opportunities for his own imaginative flights of fancy that his more conventional work did not.

CH: My own father was as dedicated to my creative fancies when I was a child, especially during my teenaged years, but it never dawned on me how remarkable that was. Maybe because in his case, he didn’t share my interests in the arts at all, which you at least had with your father. I’m envious of every word of this anecdote, in fact. Do you still have a copy of that 8mm film you two made together?

NM: Of course. There was an article about the film in HARPER’S BAZAAR, and we used to send out prints all over the country to rent at children’s parties.

A lightbulb went off in my kid head as I listened to these words. “What you do sounds like detective work,” I said. Suddenly I knew who my father always reminded me of.

CH: Deciding to write THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION is a moment in your life that feels incredibly pivotal. It spawned a film, which you wrote and were nominated for an Academy Award for. It led to your directorial debut, then STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF KHAN, and the rest of your film/TV career. Your relationship with Holmes is also one that endures today, along with TREK. What inspired you to start writing it?

NM: In high school, I was teased by kids asking, “Oh, your old man’s a shrink — is he a Freudian?” As I did not know, I asked my father who responded by saying it was a silly question — one could no more discuss the history of psychoanalysis and not begin with Freud, than one could study the history of the European discovery of America without alluding to Columbus or the Vikings. “But to suppose that nothing has happened since the Vikings is to be pretty rigid, pretty doctrinaire. When a patient comes to see me, I listen to what they say; I listen to how they say it; I am especially interested in what they do not say. I’m interested in what they are wearing, whether they are on time, what their body language is, etc. I am, in short, searching for clues — from them — as to why they are not happy.”

A lightbulb went off in my kid head as I listened to these words. “What you do sounds like detective work,” I said. He thought about this and agreed. “It is kind of like detective work.” Suddenly I knew who my father always reminded me of. I found myself wondering how much [Arthur Conan] Doyle and Freud knew about each other. Well, they were both doctors, they died in the same city, within nine years of each other. Later, I learned Freud’s bedtime reading were the Sherlock Holmes stories and when — still later — I read some of Freud’s case histories, I could not help but remark on their stylistic similarity to Watson’s Holmes chronicles. More time passed…and you know the rest.

CH: Did you consult with your father at all when writing THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION?

NH: [Not] while writing the novel, but I think my depiction of Freud owes more to my dad than the real Freud. I gave him the book to read when it was finished and he made a few helpful editorial comments — I hadn’t realized Freud was not musical — but that was it. We were both astonished by what happened next.

CH: I know it’s impossible to untangle your father from your love affair with the arts, given his formative role in that love affair, but I have to say — it’s difficult to miss his fingerprints all over your creative journey. Most people can repeatedly point to their parents regarding the adults they become, for better or worse, but I wonder if you can clearly identify him in your work beyond SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION?

NM: There’s no question you’re right — his fingerprints are indeed all over my creative life. One way or another he introduced me to just about everything. He saw that I was an artist or I was nothing, and that was the plant that got watered.

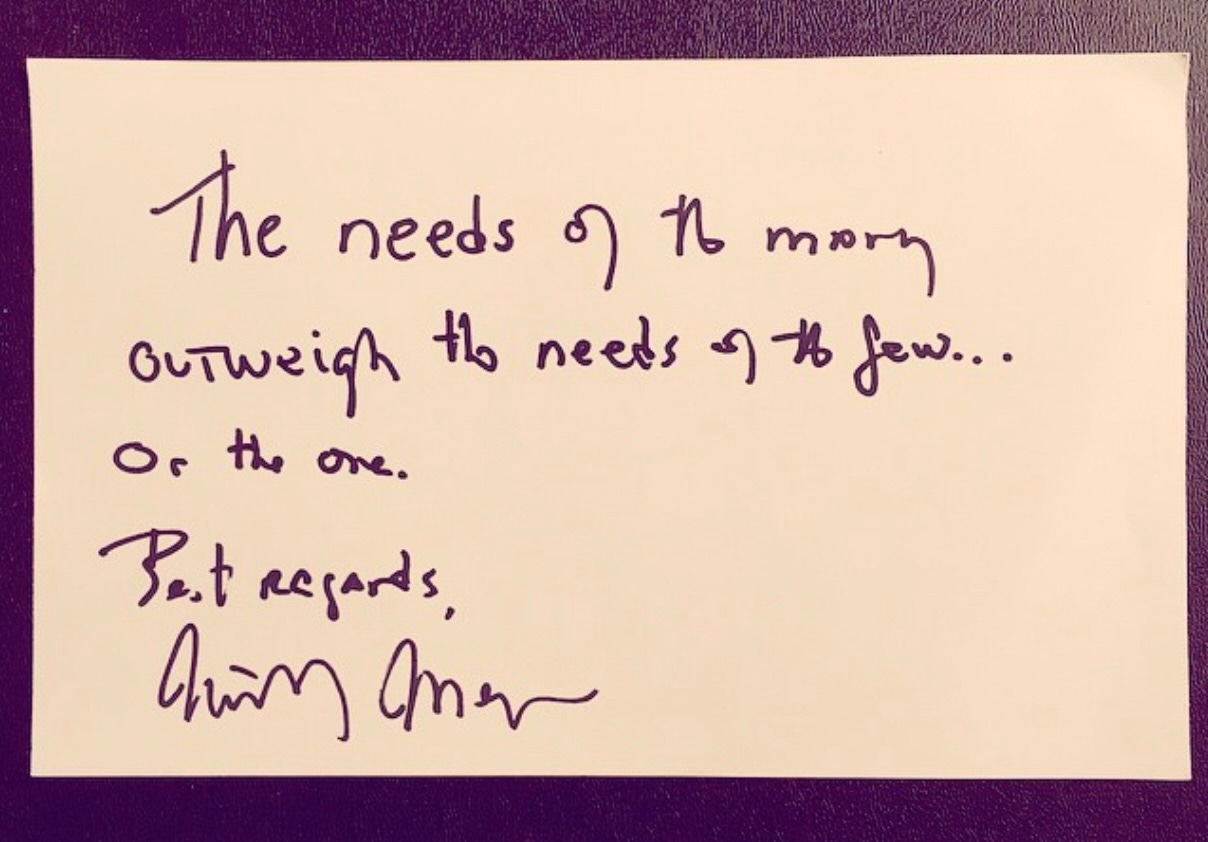

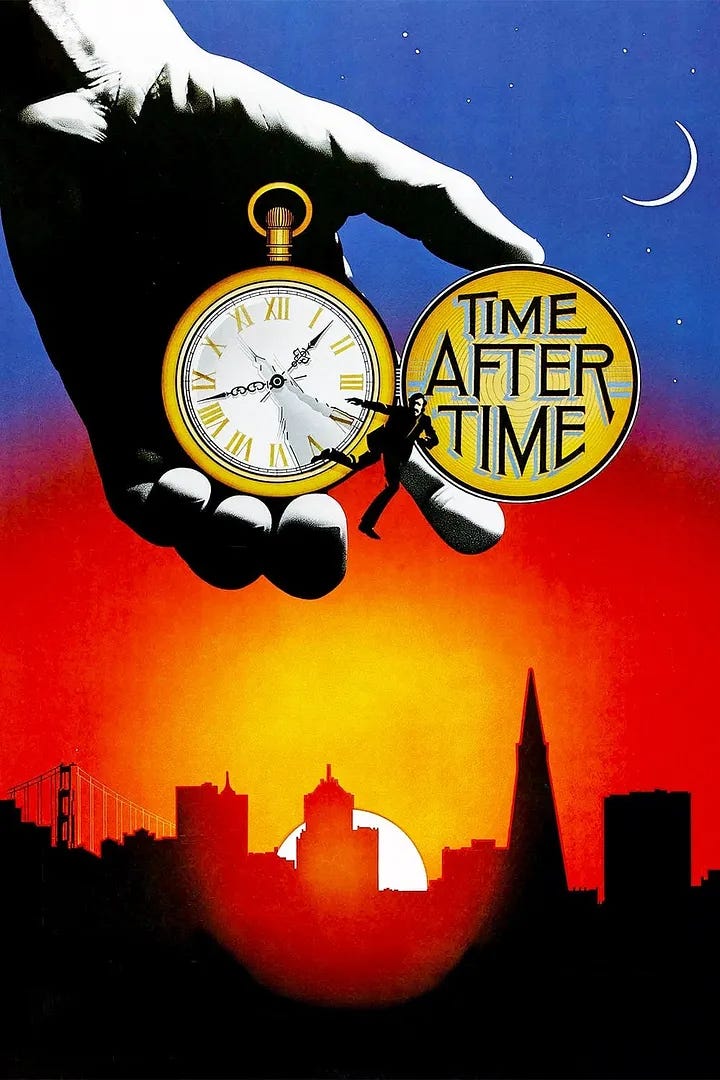

CH: SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION — the book here, not its filmic adaptation — is the first of three artworks from you released between 1974 and 1982, including TIME AFTER TIME and STAR TREK: THE WRATH OF KHAN, that dramatically influenced my own development as a storyteller and, in the case of WRATH OF KHAN, even my ethical development. Each meld popular culture and literature and, to varying degrees, history; Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud; H.G. Wells and Jack the Ripper; STAR TREK and MOBY-DICK. They also all feel incredibly specific to you, each connected in subtle ways that maybe, to be fair, only exist in my imagination. But it’s because of this that I’ve always considered them a key trilogy in the Nicholas Meyer canon. What do you make of that? What relationship do SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION, TIME AFTER TIME, and WRATH OF KHAN have in your mind at this point in your life?

NM: That’s an interesting question, but one I’m not sure I can answer. I know in a connect-the-dots sense, that THE SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION novel inspired Karl Alexander, an Iowa classmate of mine, to write his novel, TIME AFTER TIME, which I optioned after I’d read a section of it, and I then wrote the screenplay that became my directing debut. This in turn earned me a meeting with Harve Bennett, then charged with producing a second STAR TREK film for Paramount. One thing sort of led to another, but any and all thematic connections I guess were largely subconscious and I’m not good at figuring out what they mean. Which is not to insist they have no meaning, merely that I’m not clever enough to dope it out.

CH: Maybe you can’t analyze the dimensions of the artworks’ thematic connections — or maybe, I sense, it’s just not that interesting to you to be the one to consider those questions — but I think it’s very fair to say they are all deeply literary endeavors and call upon history, especially literary history, to have conversations in and about the present. Using Freud and psychoanalysis to reframe, to revolutionize a character in an exciting new way, helping him, I would argue, survive and thrive over the next fifty years. Using Wells and the Ripper to comment on the nature of violence in history and contemporary society (the Ripper’s monologue hasn’t aged a day, I think). And, perhaps most unexpectedly, using Dickens and Melville to convey WRATH OF KHAN’s themes about the present/future.

I do think it fair to say I write and make films for people who read. As reading seems to be going out of fashion, perhaps I am, as well.

NM: I think you’re quite correct and perceptive when you refer to the literary antecedents and references in my creative work. I don’t believe artists are the best judges of their work — Bizet said of the Toreador song, “Ah well, the public want shit, there it is” — but I do think it fair to say I write and make films for people who read. As reading seems to be going out of fashion, perhaps I am, as well. As for themes in THE WRATH OF KHAN, the fact — from my recollection — is that they emerged like brass rubbings as I went along, starting with what film makers sometimes call happy accidents. “Why doesn’t anyone in STAR TREK ever read a book?” I — perhaps naively — wondered when talking with Harve Bennett in my living room. I yanked the nearest volume off my shelf and it happened to be A TALE OF TWO CITIES, the only book readers recognize the first and last lines of. I’m not sure how MOBY-DICK came into it — what the shrinks might call free association — but all this stuff tumbled into place higgledy-piggledy, during the twelve days I cobbled together what became the first draft of the script. Once those brass rubbings started to reveal the writing, I wrote into those themes, but I can’t say they were planned from the get-go, because I don’t think they were.

CH: What do you think other people get wrong when they attempt similar mashups? As you know, I’ve done similar in the past in a Dark Horse graphic novel [THE STRANGE CASE OF MR. HYDE], pitting Robert Louis Stevenson’s Mr. Hyde against Jack the Ripper. I don’t think I would’ve dreamed of doing such a thing had you not rewired my imagination to think such a thing could be done well.

NM: I think what I find wrong — and I confess I don’t read a lot of these — is that they are more dependent on the gimmick of the mashup than the serious juxtaposition and exploration of the characters. When I put Holmes together with Freud, I was taking these two people quite seriously as personalities, albeit one was fictional. When I wrote my novel, the only other person publishing anything all these lines, was E. L. Doctorow, whose novel, RAGTIME, came out around the same time. Same thing with TIME AFTER TIME. Wells and the Ripper may not have been historically accurate, but as fictional characters I took them both very seriously and realistically. Granted Freud and Holmes are more specific individuals whereas Wells and the Ripper represented two diametrically opposed archetypes, constructive and destructive. But still…

CH: There’s an interesting contrast between SEVEN-PER-CENT SOLUTION and the two films we’re discussing, in that, as you just said, Holmes and Freud are specific individuals locked in a specific kind of duel regarding Holmes’s addiction. In fact, the novel even begins with you blowing up the “myth” of Holmes’ great arch-nemesis by dismissing Professor Moriarty as a figment of Holmes’ cocaine-addled imagination. But TIME AFTER TIME and WRATH OF KHAN are both very much about opposed archetypes: Wells and the Ripper, Kirk and Khan.

NM: Yes, I’d have to say Wells and Ripper are, like Kirk and Khan, types rather than fully fleshed out characters. Khan is an Ahab-inspired sketch, all rage; Kirk is rational, thoughtful and compassionate, but neither goes much beyond those outlines.

Okay, Kirk is having a midlife crisis and needs to recover his mojo, and there is a moment of introspection when he realizes he’s been clever but never confronted “the Big Stuff”, but still. Interestingly in the Khan radio play I’m working on now, CETI ALPHA V, dealing with Khan’s time in exile, I am getting the chance to more fully flesh out Khan.

Truthfully, I am surprised and infinitely grateful to have done anything that has meaning to anyone, let alone many people.

CH: Let’s close in the present rather than the past, by considering legacy or, rather, the lasting effect two of these artworks has had on their “brands”, so to say. Plenty of people besides me have pointed out that Sherlock Holmes’s popularity had waned as adaptations of the character diminished in quality and probably leaned too much into a kind of popular schtick (not to say there weren’t exceptions); I think THE NEW YORK TIMES said similar in 2013. After the failure of STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE to become Paramount’s STAR WARS, there were many people who also assumed that the property had no future either. In both cases, Nicholas Meyer swooped in, identified what people loved about the characters to begin with, and, in many ways, resurrected them for good. Today, it’s nearly impossible to imagine the 21st centuries’ takes on Holmes without you or the TREK franchise without your course-correction — which is probably why it endlessly references WRATH OF KHAN. How do you feel about the decades-long relationships you have maintained with both, and, maybe more interestingly, how do you think those relationships and the many books and films produced in both worlds have shaped you as a storyteller and as a person? I can’t imagine it’s anymore possible at this point for you to extricate yourself from them as they could extricate themselves from you.

NM: Truthfully, I am surprised and infinitely grateful to have done anything that has meaning to anyone, let alone many people. Doyle was annoyed that people valued his Holmes stories — he took about a week to dash one off — compared to the research and pains he took over his historical novels like THE WHITE COMPANY, but I don’t have the same annoyance. Sullivan also bemoaned that his “serious” music was not as beloved as what he wrote in collaboration with Gilbert. Maybe Bernstein sighed that WEST SIDE STORY was more popular than some of his labored symphonic works, but what can you do? Audiences may be stupid but they are never wrong. It is true that I feel most of my best screenplays have never been filmed, but I think it would be, at the least, churlish of me to look down my nose at stuff I’ve done — and I include THE DAY AFTER (1983)— that has affected so many people. I feel quite lucky.

Nicholas Meyer’s latest Holmes novel THE RETURN OF THE PHARAOH: FROM THE REMINISCENCES OF JOHN H. WATSON, M.D. is on shelves now.

If this interview added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. Nick was kind enough to offer a blurb, which you can read below. You can order PSALMS here no matter where you are in the world: