Q&A: TV Showrunner Amy Berg Has a Lot of Fight Left in Her

The "WARRIOR NUN" and "JACK RYAN" writer talks craft, her favorite kind of porn, and why the WGA is going to win this strike

When I lived in Los Angeles, Amy Berg was a screenwriter I always had the sense had just left the production company offices or party I’d just arrived at or, vice versa, was imminently expected after my own departure. At one point, I got home from a friend’s house, hopped on Facebook, and saw her in a photo just taken at said house. Ships passing in the night, in other words. Disappointingly, I moved abroad before we finally met in real life, but we nevertheless struck up an online relationship during the WGA’s agency campaign - which is how she came to be invited to join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations. Pretty much, I just wanted to get to know her better.

Amy is a writer, creator, and showrunner whose work I’ve long admired. She broke into Hollywood twenty-five years ago on “KENAN & KEL” and spent the next decade or so racking up TV credits until she landed her first producing title on “LEVERAGE”. “LEVERAGE” represented an exciting turning point in many ways, as it was followed by an outstanding run of series such as “PERSON OF INTEREST” and “EUREKA” - culminating in her elevation to showrunner of “DA VINCI’S DEMONS” in its third season and “COUNTERPART’s” first season. She’s since worked on and produced more stellar, wildly popular series like “THE ALIENIST”, “TOM CLANCY’S JACK RYAN”, and “WARRIOR NUN”.

(For screenwriters at all levels, I’d advise you to focus on Amy’s craft talk upfront, her passion for “competence porn”, and her thoughts on creating in the current market and why we’ll win the WGA strike.)

COLE HADDON: While I’m endlessly interested in craft, I usually don’t make it the focus of these conversations. So of course, I’m going to start off with some craft questions here. Such as, are you a vomit draft screenwriter or do you rewrite as you go along, constantly picking apart and reworking everything you’ve put on the page?

AMY BERG: It depends what I’m working on. If I’m on a television series, whether mine or someone else’s, there’s usually a point when I know the characters and the story nuances so well that I can write a first draft that’s very close to a final pass. So, I’m just rewriting as I go. But if it’s a feature screenplay or a TV pilot, there’s a lot of “finding it” in the process. You have to allow yourself to go down roads that don’t end up being the final destination. You can’t be precious about it. It’s going to be messy, and you’re going to sidetrack and backtrack a lot. And that’s okay. If you think you’ve gotten there in the first pass, that’s probably your ego talking. It usually takes some discovery to figure out who your characters are and how they fit together.

[With screenwriting,] you have to allow yourself to go down roads that don’t end up being the final destination. You can’t be precious about it. It’s going to be messy, and you’re going to sidetrack and backtrack a lot. And that’s okay.

CH: When you’re on a show, everything is typically well-outlined – often with dense treatments – by the time you move on to writing. When you’re writing on spec, or even a pilot that affords you more freedom, do you still plot the story out as meticulously or is there a lot more improv in your process?

AB: Dense treatments, to me, are a waste of time. Especially on shows you're working on and know well. If it's someone new to a series or a first-timer on the page, outlines are much more important to make sure that they understand what the showrunner is looking for. Personally, I've never done a full outline of a pilot. There was one time I did a fairly detailed beat sheet and then ended up throwing it out by the time I got to page five in script.

When the characters and story lead you in a different direction, you have to follow that, not the outline. The only people treatments and outlines really service are the ones who are giving notes. Word to the wise, though, if an executive in television or producer in film gives a note on the outline, find a way to take the note because they will always always always have the same note on the script.

CH: So, what’s the worst note you’ve ever received? Be honest now.

AB: That’s a hard question for me. I’m not sure if it’s because my memory is shit, which it is, or because I just don’t hold onto those things. Maybe it’s a self-defense mechanism to let those things go. I tend to remember changes I've made to address production concerns more readily. The one I still get a kick out of was during “THE 4400” — the original — where I'd written this surveillance scene that had multiple people covering different positions on a stakeout and a high-tech van that was the center of operations. I was just a story editor, so I wasn't on notes calls. When I finally saw the cut, it'd turned into two people on a balcony with binoculars.

CH: Okay, that was fun. Now, let’s get down to real business. Paint me a picture of who you were as a kid. Where did you grow up and were the arts important in your home?

AB: I grew up in a relatively small town in Northern California. No one in my immediate or extended family works or plays in the arts. I didn't know anyone associated with the entertainment industry either. Closest thing to it were the conversations I had with the guy behind the counter at my local video store.

CH: That guy changed the life of almost everyone in Hollywood, right? He did mine.

AB: Oh, yeah. I feel like those guys were prophets inspiring an entire generation of filmmakers.

As a kid, I always lived inside my head. I knew pretty quickly I was different from other people and my teachers knew it, too.

CH: You were telling me about your childhood.

AB: I was raised in a very pragmatic household. Creative careers were something other people did. The arts weren't part of our lives aside from going to the movies or catching our favorite shows on TV, but that didn't stop me from finding my way to them anyway.

CH: How so?

AB: As a kid, I always lived inside my head. I knew pretty quickly I was different from other people and my teachers knew it, too. A few were great enough to push me to do things I would've never done on my own. I was made to audition for plays in elementary school because I was the only one who truly understood how to tell a joke. I could wrap my head around both the construction and performative aspects of it better than other kids. As a result, I was also an unintentional class clown in that I was shy and didn't speak much, but when I did, it was usually funny. Film and television became obsessions around the same time, and I started to realize that they weren't in fact magic but rather there were creative forces behind the scenes that brought these things to life. What a job that must be...for other people to have. It wasn't until college that I realized it could be a reality for me, too.

CH: Was there one artwork that was seminal to your development as a person and, probably more importantly, storyteller? I mean, the one everything you’ve ever done can be traced back to in some way.

AB: What's funny is that if we'd conducted this interview when you first asked months ago, I wouldn't have as cool a story as I do know. There was one movie that I became preternaturally obsessed with for reasons most of my friends couldn't understand – SNEAKERS. To me, that's a perfect film. It’s full on "competence porn," which was a term born out of our writers’ room on “LEVERAGE” but now everyone uses it.

CH: Jesus, I love that term!

The simplest explanation of [competence porn] is that we love watching people who are really good at what they do being really good at what they do.

AB: SNEAKERS is the embodiment of that. The simplest explanation of it is that we love watching people who are really good at what they do being really good at what they do. There are a few scenes in SNEAKERS that really resonate with me, like when Whistler is having Bishop describe the sounds he heard from the trunk of a car or the team using Scrabble letters to unscramble a coded phrase. I just fucking love that stuff. I'm the kind of person who would rather APOLLO 13 be just two hours of those guys in a room trying to fit the square peg in a round hole using only what they had on the table. I guess at the end of the day, it's that I appreciate the craft of what went into building scenes like that – and you can find a lot of that reflected in my work. Hell, I still remember the day John Rogers raced into my office on “LEVERAGE” to tell me to fuck off because I'd written a scene with a particularly fun bit of competence porn.

CH: Wait, you said this story is only newly relevant. What happened?

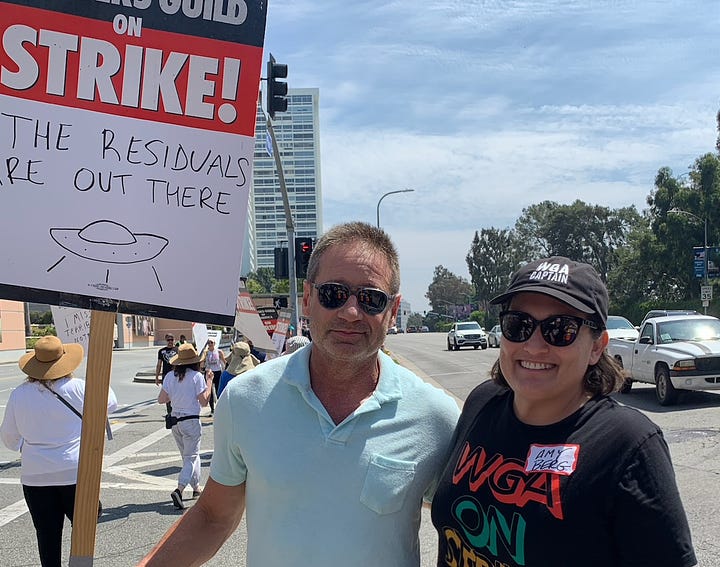

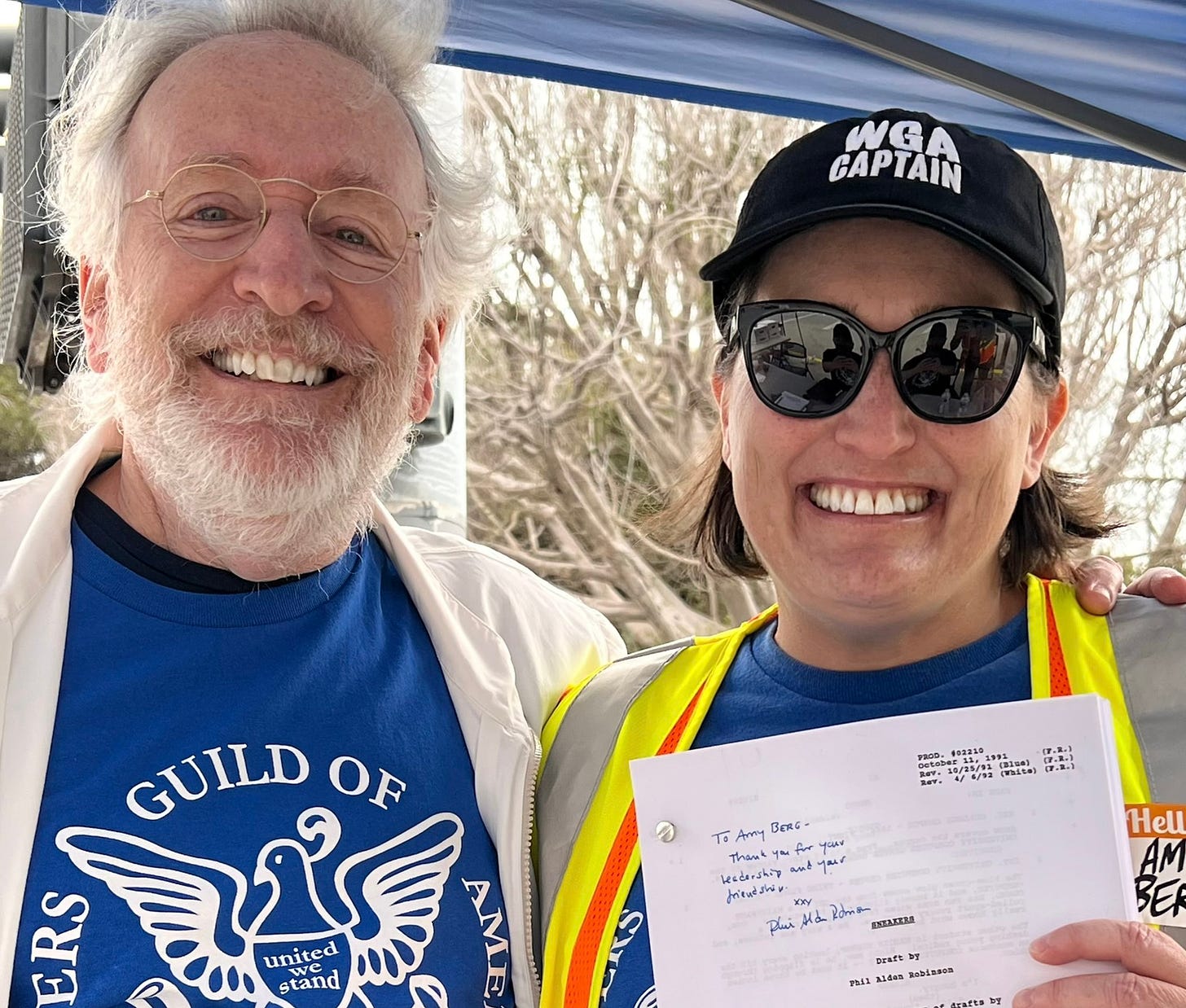

AB: We’re in the middle of a writer’s strike right now. And two weeks ago a lovely white-haired gentleman handed me his WGA card at the check-in table on our picket line at Fox. I saw his name and then promptly made an ass of myself. It was Phil Alden Robinson, who'd written SNEAKERS along with FIELD OF DREAMS and a bunch of other great films. We got to talking and I was able to tell him just how much SNEAKERS meant to me. He was incredibly gracious, and the next day he came back with a signed copy of the script. I may have cried a little.

CH: Shit, I’m crying for you. That’s amazing. I had the amazing good fortune to become friends with one of my heroes, Nicholas Meyer, who wrote and directed STAR TREK II: THE WRATH OF KHAN amongst others. I mean, hero worship can be problematic, but I’m a talent junky. One of the great joys of being in the arts is getting to meet – and occasionally come to call friend – people I respect and admire.

AB: If you told Kid Me that Grown-up Me would be hanging out with the cast of “STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION” I would’ve laughed you out of the room. That was my other big obsession growing up, and now I’ve worked with a lot of them and count them among my closest friends. It still blows my mind sometimes. I mean, I had that cast photo on my wall.

CH: Okay, so you came from a typical working-class family. Arts were a thing you enjoyed, but not something anybody took seriously as a potential career. And you said it wasn’t until college that you realized you might be able to do it yourself. What led to the decision to defy your parents’ pragmatism and become an artist?

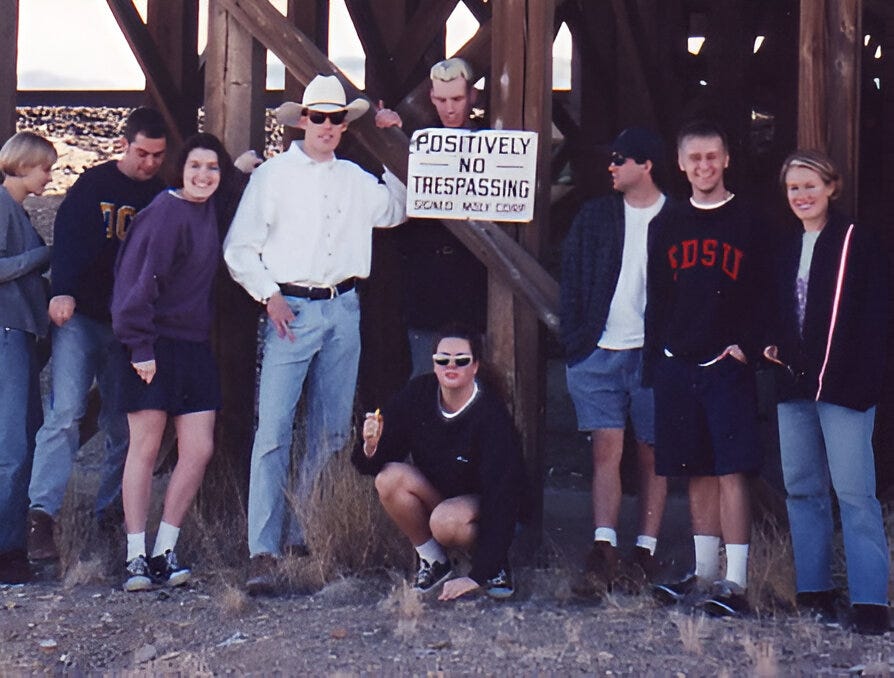

AB: My freshman year in college I helped start a film club at a school without a film program. It was just an outlet for some of my creative juices. I had friends in the drama program, so we were just fooling around shooting stuff. But I never considered film school as an option until I had a literature professor pull me aside one day. She’d given some assignment where we had to explore character motivations in a play, and I’d framed my essay from the point-of-view of a theater director working with a group of actors on their performance. She forced me to read it aloud and then we talked after class. She encouraged me to look at film school, so I did. And ended up transferring to one.

CH: Was that initial decision to become a screenwriter, or did you consider another route to a creative life first?

AB: I think everyone envisions themselves as a director first, for whatever reason. Probably because it was so glamorized, particularly for those of us who grew up in the eighties outside of Hollywood. But I realized that's not where my interests or talents lie. I love the origination of ideas more than translation of them to screen. I also prefer sitting with things and letting them marinate, so the pace of a set doesn’t really gel with how my mind works. It's also why I no longer write half-hour comedies. It's all a little too fast for me.

I think everyone envisions themselves as a director first, for whatever reason. Probably because it was so glamorized, particularly for those of us who grew up in the eighties outside of Hollywood.

CH: I look at all the TV series you’ve worked on, many that I’ve watched and enjoyed or vociferously loved, and it’s hard not to use the term “genre” to describe most of them. Would you agree with that assessment?

AB: I guess you could say I’ve written a lot of science-fiction, or a lot of spy shows, but that’s only because the industry likes to put people into boxes, and you end up staying there a while. Truth is, I have written a lot of those things. But, if you look at the original stuff I’ve worked on, the stuff I’ve sold or written on spec, you’ll see that none of it falls into either category. I’ve done a little of everything at this point. Personally, I think it’d be fun if by the end of my career I can say that I’ve written in every genre there is.

CH: You entered the film/TV business in the twilight years of its Golden Age, as I consider it. Before the Dark Times, before the streamers. Can you contrast those early years of your career with the current professional landscape you see around you?

AB: In the Before Times, you had studio heads and network honchos who considered themselves creative executives. And they actually were. They cared about the quality of their product and they put their faith in the people they hired to make the right calls. They also competed with one another to put out the best content. Content they, themselves, would be proud of. But that kind of competition doesn't exist anymore. Now you have these giant conglomerates gobbling up one another in a race to be the biggest rather than the best. They’re taking on tremendous debt yet answering to shareholders who only care about profits. It’s absurd. On top of that, with the streamers you have these tech companies running things the way they’re used to running them. To them we’re not people, we’re data points. And that’s reflected in how they judge our value.

To [tech companies,] we’re not people, we’re data points. And that’s reflected in how they judge our value.

CH: Humans don’t even seem to factor into the creative conversation at all anymore.

AB: One of the biggest challenges is that decisions to greenlight movies or renew shows now comes down to what some algorithm says. Fan appeal, critical acclaim, and even success hold little weight when the only metric they care about is an artificial computation.

CH: “WARRIOR NUN” comes to mind, a show you contributed significantly to. It was a critical smash. At one point, it was damn near 100% on Rotten Tomatoes’ aggregator. It’s still way up there. The audience score is even higher. When it dropped, everyone was talking about it on social media. You don’t get that kind of word of mouth if people aren’t loving it. I saw it, and I understand why they were. But then Netflix canceled it. How do you make sense of that? I read the news of how your hard, brilliant work was rewarded and I can’t help but despair and wonder, “What’s the point?”

AB: Yeah, I totally get that. It’s tough out there right now. There was a time when cancellations were heartbreaking yet there was a reason for it that made a modicum of sense. Now shows are vanishing off platforms and there’s no rhyme or reason to it.

CH: Has the environment streamers created, this ecosystem where the strongest don’t necessarily survive, where success can go unrewarded and audience loyalty can’t be fostered – has it had any impact on your creative process or the joy you find in it? Basically, how has it affected your relationship to your career, how you pursue your art, your passion for what you do? That is, when the WGA is not on strike, of course. I find it all so toxic, I daydream endlessly about how to find creative satisfaction doing literally anything else, which, frankly, breaks my heart.

There was a time when cancellations were heartbreaking yet there was a reason for it that made a modicum of sense. Now shows are vanishing off platforms and there’s no rhyme or reason to it.

AB: Like an escape route if you had to abandon the business? Or just in your day-to-day because you can’t find satisfaction in the work you’re doing anymore?

CH: Both, I think. Though certainly the escape route is always at the forefront of my mind. As you know, I had a novel come out last year. I’ve written a second one. I’ve written a play. I write this newsletter. I just want to write and tell stories and talk about art.

AB: That’s admirable, and too exhausting for me to even consider. But it also goes to show that our line of work isn’t reliable as a source of income anymore. It’s sad to see how this business has changed to benefit those who don’t actually create anything at the expense of those who do.

CH: Absolutely.

AB: You asked if it’s harder to generate the same enthusiasm that we used to have for what we do. The answer is, of course, yes. Traditionally, you love something, you find people who love it, too, and you go make the thing. It wasn’t easy, but it was fulfilling because the passion was there on all sides. Now you have to expend a lot more energy finding the passion because the process has become so muddled, not to mention completely reliant on all the free work we’re expected to do. That’s part of why we’re striking. We’re striking because we love this business. We love making television. We love making movies and video games and podcasts.

At the end of the day, we love telling stories and, speaking for myself, I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. You have to swim through some muck now to find them, but there are still other folks out there with the same passion for this industry that you and I have. I see it every day on the picket lines in the faces of those desperate to protect our craft for those who come up behind us. It’s why I volunteered to be a strike captain and lot coordinator. There’s still a lot of fight left in us - and it’s why we’ll win.

You can find Amy Berg on Twitter.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

"our line of work isn’t reliable as a source of income anymore" (sighs)