Q&A: Screenwriter Scott Rosenberg Has Some Thoughts About 'Beautiful Girls'

The scribe goes deep into the personal stories behind the inception and writing of one of my favorite films of the 1990s

Some films become yearly events in our lives, and that’s largely been what Beautiful Girls has been for me for almost a quarter-century now. As the temperature drops outside, bringing with it memories of bleak winters growing up in Michigan, I inevitably shuffle to the shelf where my physical film collection lives, search through the piles of titles I recklessly stack there (organization is not my strong suit), and retrieve my twenty-year-old DVD copy of it. This is what amounts to time travel for me.

Released in 1996, two years after I graduated high school, Beautiful Girls weaves together the lives of a host of working-class stiffs during the week of their ten-year high school reunion. It’s anchored by the character of Willie (Timothy Hutton), who is unique amongst his friends as he left town to work in the arts - something that has always spoken to me, as the same could be said of me by those I grew up with. He’s in crisis when we meet him, but this isn’t much different than the rest of the gang; they’re all struggling with the men they’ve (failed to) become, you might say. Willie, in particular — on the verge of trading his dreams for a steady paycheck — is drawn to the youth and potential of a wise-beyond-her-years thirteen-year-old neighbor who might yet live a life as full of excitement and satisfaction as the one he hasn’t. Their brief relationship — he’s the Pooh to her Christopher Robin, as he tells her — is the spiritual heart of the film.

As written by Scott Rosenberg, Beautiful Girls is a hilarious and painfully realistic depiction of coming-of-age — or, rather, failing to — in a town ripped out of a Springsteen song. This probably has something to do with the fact that the town in question, as well as the idiosyncratic characters he inhabited it with, are deeply autobiographical to the scribe. You might even say he grew up with them…because he did, as you’ll see. I’ve long wanted to discuss all this and more with him, but, despite knowing each other peripherally in Hollywood for close to a decade, we’d never had a chance to sit down face to face. Well, it took nearly a year of persistence, but we finally nailed down a time to Zoom this past July as part of my artist-on-artist conversation series. Mission accomplished - and I was not disappointed by the experience.

Now, if you’re a long-time reader here at 5AM StoryTalk, you know these chats tend to concern an artist’s broader career. In Scott’s case, this would involve the films Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead (1995), Con Air (1997), Gone in 60 Seconds (2000), High Fidelity (2000), Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle (2017), and Venom (2018) - amongst many others. We might also discuss the five TV series he created, too — including “October Road”, which you’ll find has a connection to Beautiful Girls.

But not this time. Instead, Scott and I are about to go deep into a single, seminal piece of artwork - the inception of Beautiful Girls’ story, the craft and exquisite precision that went into the writing of its script, and the film’s enduring popularity across generations. Before you dive in, I encourage you to first read “This Is How You Introduce Characters: Breaking Down the Opening of 'Beautiful Girls'", which was published here a few days ago; in it, I dissect in great detail the first ten or so minutes of the film, which I’ll likewise be discussing with Scott. It will immensely enrich this conversation, I think.

COLE HADDON: You didn’t have a PDF of the shooting draft of the film for me to read, but I dug up one dated January 8th, 1995. The film was released just over a year later, so I have to assume this is pretty damn close to what director Ted Demme went into production with. But as I read the opening, I’m immediately struck by how structurally different it is. For example, Willie doesn’t make his grand entrance until eleven pages into it and we never see him in the big city, struggling as a musician as we do in the film. I’m curious, how did the opening’s final structure come about which, as I described earlier, is very much framed by Willie and almost plays like a long montage?

SCOTT ROSENBERG: Yeah, it's funny because I haven't seen the movie in forever, but it's also so long since I looked at that script. The one you sent me, I'm not sure if that was the exact one that I sold or if it was an early draft after that, but it didn't open with Willie. I totally forgot about that. It was, like, a late add I'm pretty sure once we were shooting. No, it was at the end of the schedule. No, it might actually be – so, this is the problem, this is maybe why subconsciously I've been avoiding you for so long. It was thirty years ago and I don't remember a lot. I mean, I kept a journal back then, but I am not where my journal is, so I couldn't even go excavate it. But I do wonder if that was a Harvey [Weinstein] move, you know what I mean? That after we tested it, Miramax was all like, “Well, we're meeting all these people we don't know, but not our protagonist.” It feels very studio notey to open with who is essentially the protagonist, so the audience has a way in.

CH: It does. As opposed to how you did it in the script—

SR: —which is you meet a whole bunch of people – “Willie's coming, Willie's coming!” – and then he doesn’t show up for twelve minutes. But it was really interesting looking at the script again.

CH: Maybe I should ask you about the origins of the screenplay. I know some, especially from what you’ve written on Facebook about it, but I always prefer to hear from the horse’s mouth.

SR: Honestly, I think that the story behind it is super simple in so far as it's sort of baked into my own bio. I’d finally got an agent and a few things going, but nothing great. And then my father got sick with cancer and died, and I wanted to deal with it. And then I wrote Things to Do with Denver When You’re Dead, and it exploded. It was just one of those scripts that everybody was reading it. The first thing I got off of it was Con Air, and they, in those days, Disney made you write a treatment before they would send you to script. So, I wrote this 25-page treatment, and I submitted it, and I went back to my home in Boston and a relationship that was ending after seven-and-a-half years. And I was seeing what was going on with all my buddies and everything else, too. And every single one of these characters in Beautiful Girls is based on one of my friends. It was this terrible, terrible winter, and the snowplows were going by, and I just was like, that was the thing I knew I had to write about.

CH: You were compelled.

SR: Yeah. I was so tired between Denver and Con Air. I was so tired of writing back in those days in general. It was crazy. We were throwing around the N word with Con Air and there were all these vile, disgusting, racist, angry men. And I was just feeling like I wanted to do something different. I genuinely was listening to the Counting Crows, a song, a line that I completely stole and put in the movie – “Mr. Jones” – where he says, “We all want something beautiful.”

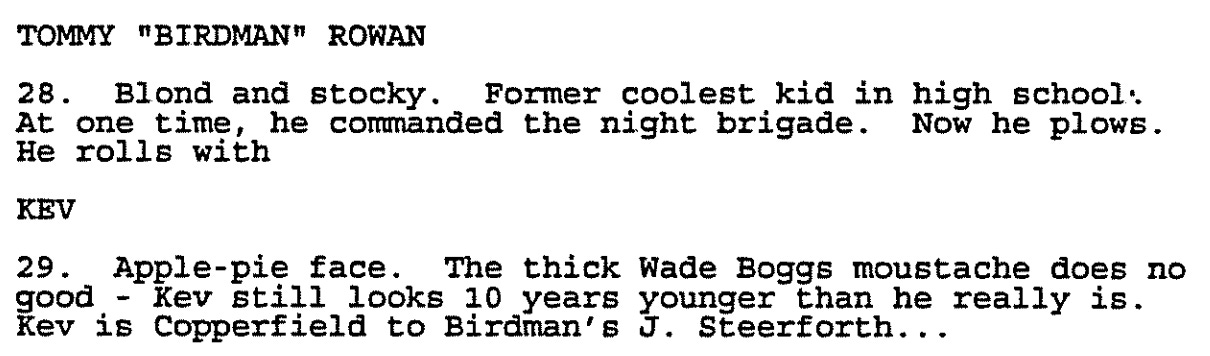

SR (cont’d): And I walked into the house I grew up in – my brother remembers it so clearly because our father had passed, my mother was living elsewhere, and it was this crazy, crazy snowy, snowy Friday. And I said to my brother, “I'm going to go in my room and I'm going to write a movie called Beautiful Girls, and it's going to be about guys.” And I closed the door and no joke, I came out a week later and the script was written. And so, I think to answer your question in a very sort of long-winded way – the economy of the script? God knows I'm not an economic economical writer. The economy sort of came from my absolute familiarity with who I was writing about. I mean, Birdman was literally Birdman.

Note to reader: In this scene from Beautiful Girls, Willie (Timothy Hutton) returns to his childhood home, which is now a sad place after the death of his mother. His brother (David Arquette) greets him.

SR (cont’d): It’s funny because you don't realize when you write a movie that the movie's going to get made. Certainly not then. And I remember – I’m jumping ahead here – but panicking when it came time to actually make it. Birdman and Mo were the only two real names.

I went to Teddy and Cary Woods, the producer, and I said, “Yo, I'm not comfortable with some names.” I never told them any it was real. “I was thinking Birdman and Mo. I think I can do better.” And they're like, why? “I just think I can do better.” So, I spent the weekend coming up with literally seventy alts for both names and handed them to them both. I mean, seventy fucking alts. And they both read them, and as expected they were like, “Nope, we like Birdman and Mo.”

CH: [Laughs] Amazing. It’s easy to watch the film and imagine how personal it must’ve been to the screenwriter, but this takes it to an extreme level.

SR: I knew exactly what I was writing, and I didn't feel the need to censor myself.

CH: Okay, so I have some forensics questions, similar to the one about Willie’s intro. What I’ll start with is, what fascinates me about reading the script – but also watching the film produced from it – is your writing was so fucking precise thirty years ago. For example, there's this class anxiety that's going on. These are working-class, salt-of-the-earth characters. But at the same time, the script and film are loaded with endless literary references. I mean, in the first two pages alone, there are references to Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy in your descriptions. Do you think you had such literary aspirations as you wrote? As in, did you have a tone, a book, an author or such your imagination was trying to vibrate at the same frequency as while working?

SR: It’s funny you mention it. Because when the movie came out, a lot of the reviews repeated the same form of criticism - how “the click-click-clicking you hear on the film’s soundtrack is Scott Rosenberg’s typewriter! Does he really think landscapers and 13-year-old girls talk like this?”

And I remember having a brief panic attack about it because it’s the way I always chose to write, putting improbable words and thoughts into unlikely mouths of characters. So, yes, I was kind of freaked out. And I called Jim Brooks — whom I was working with at the time — and I said, “This is what they are saying about how I write! Is that bad?”

CH: What did he say?

SR: He said, “Buddy, it’s not bad at all. It’s why we go to the movies! Does the cashier at your local movie theater look like Michelle Pfeiffer? Does the fireman look like Johnny Depp? Noooo. Do people talk like Billy Wilder has them talk? Noooo. Movies are about fantasy. Aspiration! Take it as a compliment.”

And I did - and never worried about it again. As far as any literary references in the stage direction, well, I just like to make the writing fun for both myself and the reader, so a few literary allusions, song lyric references, etc. are just to keep things lively. I just looked at the script and was reminded of the description of the Birdman. I said at one time he “commanded a night brigade” or something like that. that that's a line from a Springsteen song.

CH: “Growin’ Up”.

SR: I was very, very comfortable with – and I still am to this day – to write like that only in the stage direction.

CH: Here’s another one for you. When you introduce the Birdman, you describe him as driving a 1986 pick-up with an 8-foot plow. When you introduce Paul, he’s driving a 1984 pick-up and a 7.5-foot plow. In a relationship with a lot of rivalry baked into it, you establish that power dynamic through the age of their trucks and size of their plows. Do you think you were conscious of that? Because I’ve rarely seen a script so elegantly demonstrate so much in two quick details that might otherwise seem to have no relevance to the story.

SR: Oh, yeah, for sure. Specificity is so important, even if you're dealing with a minor subculture like this. When I wrote it, I literally called Birdie and said, “What kind of plow do you drive?” And I called my friend Scott, whose nickname was Dolly, who Paul was based on to a certain extent – the model fascination was me, not him – but he lived with Birdie. Again, I cannot stress to you how true life that was. The Rosie O’Donnell character didn't exist, the Uma Thurman character didn't exist, the Natalie Portman character didn't exist, and the Pruitt Taylor Vince character didn't exist. But as far as the guys go and Mo's wife – and the triangle that Birdman found himself in – that was all real.

CH: You put your friend’s affair in the script?

SR: That movie outed that relationship, and that ended poorly for everyone. It was a bit of a – yeah, we can come back to that later.

Note to reader: In this scene, one of the earliest in Beautiful Girls, the Birdman’s affair with his high school girlfriend is front and center:

CH: Given how autobiographical the script was for you – at least, emotionally speaking – why did you choose to make Willie a musician instead of a screenwriter?

SR: Just because writers are boring.

CH: [Laughs] Fair.

SR: But I still wanted him to be creative. I wanted him to do something creative. So, I swapped the piano in for the typewriter, you know what I mean? It was just that, I wanted him to have not found his footing, and he's kind of struggling. In real life, I was the only one of my friends who had done anything creative. Again, they were all really just very blue-collar guys. The mo guy was an accountant, but everybody else was, they were landscapers, they were cops, they were electricians. So, it was just that I wanted Willie to be just more introspective, more of a thinker, all that, because that's the guy that would be struggling with the question, “What do I do? What do I do in this relationship?”

The one part that kind of makes me cringe now is he's debating whether to take a real job or something. Isn't that the thing he's torn about? You're so much more familiar with it at this point. I wish I had a chance to read the script, but does he even say what it is?

CH: God, I think it’s in paper. It’s a sales job, though.

SR: Which is kind of corny in hindsight, but at the time, I think it was sort of just giving him one more thing that he's struggling with.

CH: Okay, so you’ve written this deeply personal script. What happened next?