Q&A: Screenwriter Sarah Phelps on Why She Writes (the Really Long Answer)

In a sweeping interview, the acclaimed British writer discusses her Agatha Christie adaptations, 'unlikeable' female characters, and working through a brain injury to finish her latest series

“Well, she’s fucking brilliant, isn’t she?”

This was just one of the many responses I received from British screenwriters when I shared the news with them that I was currently engaged in one of my artist-on-artist conversations with Sarah Phelps. Her name elicits this kind of (often curse-laden) enthusiasm because she is one of the most respected and celebrated screenwriters working in U.K. TV and, by the estimation of myself and many others, the world.

Amongst Sarah’s many accomplishments are “Great Expectations” (2011), a now iconic quintet of Agatha Christie adaptations (2015 to 2020), “Dublin Murders” (2019), "A Very British Scandal" (2021), and, most recently, the horrifying, heartbreaking, achingly beautiful "The Sixth Commandment" (2023). There is a darkness to much of her work, in that it scratches and claws its way under the belly of British society, exposes its grotesquerie, and lays it bare for all to see with, variously, delight, gothic thrills, and divine wrath - or maybe we should call it a screenwriter’s wrath. This said, I find it equally intrigued by such mercilessness as it is mercy.

This is easily the most comprehensive artist-on-artist conversation I’ve ever had for this series, digging into and dissecting her work on her Christie quintet, "A Very British Scandal", and "The Sixth Commandment", in particular. Because of that and the fact that many of the series we discuss are not necessarily widely known outside of the U.K. and U.K.-adjacent territories, I’ve taken the unusual step, for this Substack at least, of breaking our chat down into sections. Most come with introductions to set up what’s about to be discussed for the Sarah Phelps neophytes who want to learn from her work, craft, and experiences. And trust me, there is so very much to learn here. Enjoy!

BEGINNINGS

COLE HADDON: Sarah, I’m going to skip trying to express just how excited I am to get to talk to you about your work and just say I am. I want to start off by trying to wrap my head around how you work because you’re easily one of the most prolific writers I can think of. I don’t mean you’ve written many successful projects or anything like that, rather how many episodes of television you’ve actually written over the past two decades. I did the math here, and there was a stretch from 2002 to 2016 that you were writing an average of just over ten episodes of TV a year. These were produced episodes, which I only point out because I’m confident there was other development in there that never saw the light of day. That is an almost super-human pace, made all the more impressive by how you constantly shifted between genres. Can you talk about this first part of your career and what it taught you about your craft and yourself?

SARAH PHELPS: Thanks for inviting me to this. So, okay…yeah, I wrote many, many episodes of TV early on in my career. My first actual writing gig was working for the BBC World Service soap, the small but truly mighty “Westway” and from that I got invited to do the shadow scheme on the BBC soap "Eastenders", a show I adore, have watched religiously and passionately. I just…hit the ground running and, by the time I’d written my second episode for them, I was asked to come and storyline and then, it was just all guns blazing. At the same time, I was writing “No Angeles” for Channel 4 in the U.K., a comedy-drama about four nurses in Leeds, created by Toby Whithouse - who subsequently created “Being Human”, another fantastic show I wrote on. And at the same time, I was also working on development projects and writing guest episodes of other shows with varying degrees of success. Some I got sacked from, which was annoying but gave me great anecdotes. Some I walked away from because we weren’t the right fit and I should have trusted my gut from the start.

CH: I’ve never had a problem with writing at a racehorse’s clip, but what you’re describing really is staggering.

SP: If I’m honest, I don’t think I ever thought about how much I was doing, just that I was always doing it because I loved it so much and was so deeply invested in all the stories and the characters. Plus, there was some familial chaos going on and it was a bit, “Fuck, if the hardest thing I’ve got to do today is write an episode of “Eastenders”, then I’m laughing. Sometimes, I’d look up from my desk and think how much my life had changed. I never imagined for a second this would be my life, you know, and now it was - and I hadn’t had time to notice it. Then there would be a production issue or a new deadline and I just cracked on with what needed to happen next.

CH: Is there a part of you that regrets not being able to appreciate it more because of how much you were working? I can’t help but hear a screenwriter’s version of “Cat’s in the Cradle” playing in the background.

SP: But what would appreciating it look like? I stretch out on a sumptuous chaise longue and call for my opium pipe? I just wanted more more more. Greedy, you see. And I was so stunned to be doing this that I just wanted to do everything. Also, there’s a fair dollop of the dread imposter syndrome, that if you take your foot off the pedal for even a moment, someone will sidle up to you, put a heavy hand on your shoulder, and mutter, “Yeah, good try, now fuck off.”

“There’s a fair dollop of the dread imposter syndrome, that if you take your foot off the pedal for even a moment, someone will sidle up to you, put a heavy hand on your shoulder, and mutter, ‘Yeah, good try, now fuck off.’”

CH: I’ve had about thirty conversations with screenwriters in the past year now, all part of this series, and you’re the first to acknowledge how so many of us spend the first part of our career trying to outrace the imminent discovery that we are frauds despite how common I know it is amongst writers of any ilk. I think it’s vital to emerging writers to understand that even award-winning writers such as yourself — people they might admire, want to emulate, and so on — experience that terror.

SP: It never goes away. Never. It’s always prowling, licking its chops. Every new script. Every new project. Sometimes, when the terror is particularly ravenous, every single damn word.

CH: I had asked what this stretch of your career taught you about writing or even yourself.

SP: What did it teach me? Oh god, I don’t know. That I’m obsessive, for sure. I think, that I have to have a feeling for the story, an immediate visceral feeling for where the heart of the story is, and then you fight for it. And when I say fight, you have to fight for it in your first draft. Or I do. Go to war with myself to make sure the first draft is as complete as possible. If the first draft is half-baked, then too many conflicting voices come in with how it could be fixed and I just can’t work like that. I know screenwriting is collaborative, yadda yadda, and of course it is, but I have to own the world of the first draft and understand it, why the characters are doing what they’re doing, what the world smells like, how low the ceilings are, has the milk gone off, who owns the house the character lives in, can they make the rent this week, what is the terrible thing that wakes them up at 4 am covered in sweat? All of that, I have to know it and own it, all the deep, deep stuff. The who and the why and the when. The tiny abrasions, the grit, the racing heart, and the banging blood. The collaborative stuff comes later for me. I have to make sure that the people I’m working with and for can see it and believe it through my eyes, then we’re all heading in the same direction together. Christ, I sound like a little dictator. Obsessive and dictatorial. Fantastic personality traits.

CH: When my son left reception — this was in Camberwell — his teacher similarly and observed, “Well, someone has to run big corporations.” I think she meant to suggest he might be a sociopath, but all I thought was, “Orrrrr he’ll make a great screenwriter.”

SP: I have questions for that Camberwell teacher. It’s reception class for fuck’s sake - chill your tits!

CH: [Laughter]. Christ, you’re delightful.

“If the first draft is half-baked, then too many conflicting voices come in with how it could be fixed and I just can’t work like that.”

CH (cont’d): Can you tell me about your childhood? Did the arts play much of a part in it?

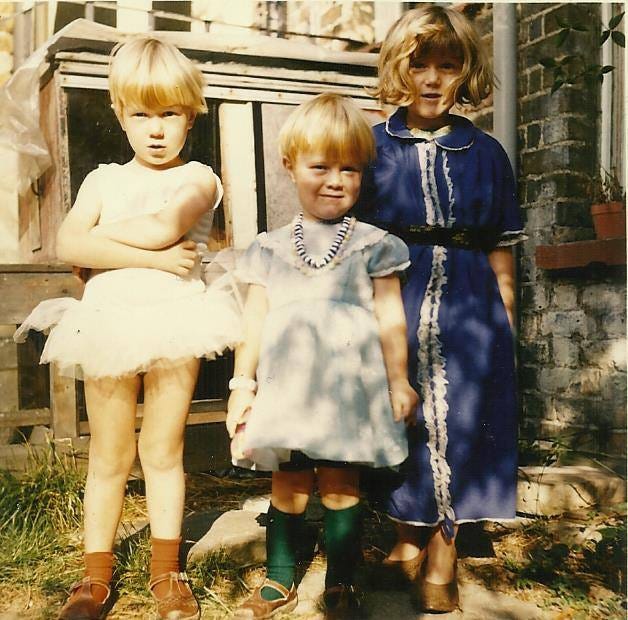

SP: Yeah, the arts were really vital. I’m the eldest of four, I’ve got three brothers, but we’re all born very close together. My youngest brother is exactly five years, five weeks, and five days younger than me. In all the family photos when we’re kids, my mum and dad have this 1,000-yard stare from the sheer chaos of all these feral children. And, god, we were feral. But we were so lucky, my brothers and me, because we grew up in a house full of books and art and history and music. My dad was a scenic artist for film and TV. Sometimes his work was painting huge areas of sky or parquet flooring and sometimes it was painting Beatrix Potter characters or Tudor-style portraits. I remember once, he had to paint a pastiche in the style of an Italian master for a drama about an art theft. We watched the drama, and there was my dad’s painting and a deranged villain slashed it with a butcher’s knife. My dad sighed and said, “Six weeks of my life - six bloody weeks!”

CH: I’m sure you’ve also had that same reaction once or twice while watching what’s been done to your work onscreen.

SP: Genuinely, I’ve only had that experience twice so far. The absolute gut punch of looking at what’s on-screen and thinking, “What in fuck has happened?” In one of these experiences, which was like having my skin flayed off, the first block director emailed me an apology for not treating the original material better and allowing it to be taken in another direction - but he was under a lot of pressure from execs blah blah blah. Well, fuck him, he’s a grown-up, should’ve stood his ground and fought. Anyway. I’m totally over it, it doesn’t claw my soul with shame and I’m not curdled with bitterness over it. At all.

CH: [Laughter] At all, of course. I created a ten-episode TV series that Sky aired. I still haven’t been able to bring myself to watch more than a few episodes of it – so I am incredibly envious of how much better your work has fared overall.

SP: I’m really sorry, it’s the shittiest of feelings. I was so overwhelmed with shame when I saw the work. Shame and fury. I still feel belches of the shame of being powerless to influence decisions made by people I’d been dumb enough to trust. Also, I bet they’re not feeling any shame.Ugh. But it is hideous. That’s nearly ten years ago now, but my brilliant friend Tony Jordan – creator of “Hustle” and “Dickensian” and many others – said “You’ve got to bounce off the ropes and come back swinging.” Dukes up, Cole. Dukes up.

“I still feel belches of the shame of being powerless to influence decisions made by people I’d been dumb enough to trust.”

CH: I’m still fighting the good fight. Sorry, I’ve distracted you. We were discussing your childhood.

SP: We were encouraged to draw and paint. My dad taught us the basics of perspective and things like, but let us get on with it. We painted on the walls and radiators, too, which didn’t go down quite so well but there we are. And reading. I was obsessed with books, had my own library card. I was allowed to spend time on my own just reading without being told to do something else. Just having my face in a book was a completely valid way of spending the day. And I’d read anything and everything. Someone I knew when I was living in Florence, working my way through the entire works of Mazo de la Roche while being covered in infected mosquito bites, told me I lived too much in my head. Yeah, probably but it’s the books that saved me really. The books and the horses.

CH: Is there a novel — or, really, book of any kind — that defines these memories of your childhood when you think about it?

SP: Oh god, loads. Penelope Lively, Rumer Godden, Patricia Leitch, Monica Dickens, Barry Hines, Laura Ingalls Wilder — and those books are wild! — and two books my mum had had in her childhood as a pony mad girl, as I was and still am, Silver Snaffles and The Wednesday Pony by Primrose Cummings. Everyone’s shitty about pony books, but I learned the word “execrable” from Silver Snaffles so. The Endless Steppe by Esther Hautzig, Summer of My German Soldier - my god, what a brilliant book by Bette Green. If I had to pin down one novel from childhood, it would be Fireweed by Jill Paton Walsh and The Greenage Summer by Rumer Godden, both outstanding - romantic and strange and lost and heartbreaking. Just brilliant. That’s two novels, sorry.

CH: Tell me about your mother.

SP: My mum was a teacher — history and politics — so there was always conversation about what we saw in the news, about how to read, how to interrogate language. I did very badly at secondary school, couldn’t stand it and ended up being turfed out, but at home, I was always able to retreat into reading or art. They loved comedy too, Mum and Dad, wordplay and bad puns and silliness as well punchier dramas and films. They were both, my mum and dad, in flight from the expectations of their class and family and the arts and education, for them, represented freedom and defiance, I suppose. Yes, defiance, definitely. So, yes, the entire spectrum of the arts. How important it is to be curious about the world and people and look closely, read and think closely - and how important it is to laugh. Me and my brothers are so very lucky to have had that upbringing.

“I didn’t have any idea I could get so worked up about what should be on Miss Havisham’s dressing table or how an ‘Eastenders’ character would talk about Jesus.”

CH: Earlier, you described this immediate, visceral feeling you have to have for where the heart of your stories are, especially with regard to first drafts. “I have to know it and own it,” you said, “all the deep, deep stuff.” You mentioned wanting to even know where the tiny abrasions and grit are. Your father’s career would’ve been focused on conveying such profound detail, to create something believable, something that felt true for audiences at home. Your mother taught you how to read, interrogate language, look and think closely. Am I imagining how straight this line seems from your parents to how you write and tell stories today?

SP: Yeah, must be. Though to be honest, I didn’t know I could be quite so furious about tiny details until I started writing. I mean, I was always furious about something, but I didn’t have any idea I could get so worked up about what should be on Miss Havisham’s dressing table or how an “Eastenders” character would talk about Jesus.

CH: So now, every time a producer struggles with you acting like a dictator — your joke — we know who to blame.

SP: Nah, my flaws are my own. I’m not making my poor parents shoulder the responsibilities of my character. And I think there’s only been two times I’ve butted heads with producers and execs. Mostly I want to work well and happily with people because they’ve got skills and talents that I will never possess and I want them to be happy in their work, but I have to be certain of the work I’ve given them, if you see what I mean. I’ve been called “difficult” in the past, but that’s said about women a lot.

CH: Especially in the film and TV business.

SP: It’s interesting when other women in this industry call you difficult, though. Like, really? Really? Nice gatekeeping you got there.

“Most of the time, even if I’m kicking against “notes” and “ideas”, there’s a big part of my brain that’s already working to find solutions to the questions.”

CH: You mentioned the “collaborative stuff” comes later for you, after your first draft…but that doesn’t exactly imply it comes naturally for you.

SP: I don’t know. I like talking about the work with people, but I get frustrated quickly, which is much more to do with me being hyper-aware of my own failings. I also find it really hard to spend a long time in rooms having meetings. That’s just a thing that’s always been there. Why I was not much good at school and jumped out of windows and whatever. And most of the time, even if I’m kicking against “notes” and “ideas”, there’s a big part of my brain that’s already working to find solutions to the questions, if you see what I mean. So, my angry mouth can be raging about some note being bullshit, but my mind is already chatting away, saying, “Yeah, but what if it happened like this? What if you put that there and moved this over here? What if?”

CH: Yes, I relate. I often wish producers just accepted many writers’ need to be allowed to honestly react — to have an authentic reaction I mean — before getting on with it.

SP: I think this also comes from working on a soap for so long when the turnaround has to be so fast, you’re aware that no one really has the answer, they just have the question and it’s up to you, the writer, to find the answer in the script, the story, the character, the dialogue or even the POV. It’s up to you to say, “What if?”

THE CHRISTIE QUINTET

Between 2015 and 2020, the BBC released five limited series adapted from Agatha Christie novels and short stories by Sarah Phelps. These proved controversial to some Christie devotees because of perceived liberties they took with aspects of the author’s work, but I found them each to be revelations. My gateway drug in this regard was “The ABC Murders” (2018), which was the first series of any kind my wife and I were able to focus on following the birth of our second son. The Hercule Poirot mystery, which delved into the iconic detective’s secret origins, kept me on the edge of my seat the whole time - as much because of the narrative as how I, a screenwriter, delighted at the decisions Sarah had made with the story. I quickly worked my way through the other adaptations already released, including “And Then There Were None”, “The Witness for the Prosecution”, and “Ordeal by Innocence.” A final adaptation, “The Pale Horse”, brought Sarah’s exploration of Christie to an end in 2020…or did it?

CH: I know you’ve talked about this a lot over the years, so I’m sorry to flog a dead horse here, but I have to ask about your Agatha Christie adaptations - which are so infuriatingly good. You wrote five of them over half a decade or so, which were huge successes at home and abroad. Hell, earlier this year Deadline even referred to a new Christie adaptation as the first in the “post-Sarah Phelps era”. Is it true you had never read one of her murder mysteries before you were approached to adapt And Then There Were None?

SP: Yeah, that’s completely true. They’d just never appealed to me. They weren’t on the bookshelves at home and when I went to stay with grandparents, they didn’t have any Christie either. They had every single James Bond novel, which is how I read the entire [Ian] Fleming oeuvre by the age of, what, ten? But there was no Christie and what I had seen of her and heard of her, or rather, the “world” of Christie didn’t appeal. Cosy Sunday night fare. I thought I knew who she was and what her books were. I was an idiot.

CH: What about Christie ultimately spoke to you as a storyteller?

SP: I was so surprised by And Then There Were None. Surprised and shocked by how remorselessly cruel it was, the occasional gallows humor, the mercilessness of it. It made me think of The Oresteia - you know, action begets action, you can squirm and wriggle and beg for forgiveness, but there’s no mitigation, just the unblinking eye of fate or God. No one can see you or hear you, no one is going to come to your rescue. No one. What you did, who you are, brought you here and this is the very end of your life. And it is going to be terrible. And they know what’s going to happen to them. Monstrous! It also struck me as being so subversive.

CH: How so?

SP: And Then There Were None was published in the summer of 1939, just before we went to war again after the war in which Christie served had reduced Europe to a charnel house. And here on this bleached rock are all the figures from Establishment Britain. The judge, the butler, the secretary, the playboy, the devout spinster, the doctor, the policeman, etcetera. They could all be the figures in some ludic bit of drawing room fun if you want to read the book just as a locked room mystery, but they are also the people who are supposed to be our compatriots, our neighbors, the people we can rely on in time of national conflict and war. They are also products of World War I. But underneath their respectable carapace, they’re all murderers, soused in blood and violence and yet, there’s no red mark of Cain on their brow, they haven’t been materially or existentially changed by their crime, they’ve just carried on living their solid Establishment life. And then you start to unpeel them, all the duplicity and the malice, the sexual jealousy, the indifference, the self-interest…and you see them. To me, it was Christie saying, “This is who your neighbors are, this is what authority is, this is what your countrymen do when they think they can get away with it. This is what the judge does in the dark.” I thought that was a stunning, astonishing thing to write about in 1939. Agatha, I thought, you sly bitch.

“I had this thought that you could write a quintet about England, from the end of World War I to the 1960s - and write about who we are and why we are, how we come to be here, right now, in the 21st century through the medium of murder mystery.”

CH: Okay, you’ve closed the book. She did her job and hooked you to such a degree you felt compelled to turn her work into a TV series. This was a defining adaptation for you, in that it led to a series of them. How did you decide to approach Christie from the perspective of the 21st century?

SP: While I was working on “And Then There Were None”, Britain was going into the EU referendum, one of the most catastrophic acts of self-harm ever and the language around the referendum was hideous. Nationalism, patriotism, borders, foreigners, otherness, who’s loyal, who is a traitor, what should happen to the traitors. It was vile, ugly, racist, and, as I was writing, I had this thought that you could write a quintet about England, from the end of World War I to the 1960s - and write about who we are and why we are, how we come to be here, right now, in the 21st century through the medium of murder mystery. Write the language of national identity, about history, about war, class, sex, poverty, wealth, about motherhood and servitude, about damage, about who gets killed, who kills and why. What killed the victim? Not just the weapon, but what condition, what atmosphere, what dynamic, both domestic and national, created the volatile dangerous environment where a person has their life ripped from them? So, anyway, I pitched it and…it happened.

SP: To this day I still haven’t read everything she’s written. I wanted to carry on being shocked by her and with that lunatically prolific output, there’s going to be repetitions and tropes and I didn’t want to be bored by the tropes, I wanted to be shocked by her. Her hiddenness, how cloaked she is, as a writer. There’s a real conflict with Christie, I think, between the book she wants to write and the book she knows her readers want to read. Especially post-And Then There Were None and later in her career. She gives little clues, little things that don’t fit, tonally or thematically, little throw-away details. And those are the clues I followed in my adaptations. The “what’s that doing there?” clues. I don’t know if any of this makes sense.

CH: It is, I think. But why don’t you give me an example?