Q&A: Screenwriter Beth Schacter on the Dance Between Art and Ambition

The 'Billions' and 'Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber' showrunner has a far-ranging conversation about art, craft, and trying to create something meaningful in Hollywood

Well, guys, I now understand what so many other people I know do: screenwriter Beth Schacter is fucking delightful. From the first question I hurled at her as part of our artist-on-artist conversation, she made me lean forward, laugh, and more than a few times give the “oh yeah, preach” slow nod. So, let me tell you a bit about the showrunner of “Billions” season 7 and co-showrunner of “Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber” before she and I dive into our chat.

Beth’s career as a filmmaker kicked off when she just went and wrote and directed her own independent film called Normal Adolescent Behavior (2007). She transitioned to television after this, where she wrote for a slew of series “Quantico”, “SEAL Team”, and “Soundtrack” before “Billions” creators David Levien and Brian Koppelman came a-knockin’ on her door. She joined the hit series’ writers’ room for Season 5 and 6 before being promoted to showrunner for Season 7. She jumped to “Super Pumped” after this, another series created by Levien and Koppelman. Beth co-ran the series about the rise and fall of Uber CEO Travis Kalanick with them.

Beth and I are about to have a wide-ranging conversation, to say the least. We’re going to get very philosophical about art as I like to do here — in between discussing her craft, her experiences on “Billions” and “Super Pumped”, and what Hollywood CEOs have in common with Greek gods. In particular, her thoughts on writing about the ultra-rich might help you reconsider your approach to any number of less-than-savory characters. Without further ado, let’s dive in...

COLE HADDON: Beth, I tend to get the most excited by art that provokes me in some way, that challenges me in unexpected ways, that gets me out of the comfort zone I’m trying to hide in as a terrified citizen of the 21st century. Can you tell me the last piece of art that rocked your understanding of yourself or humanity or the world in general in some way?

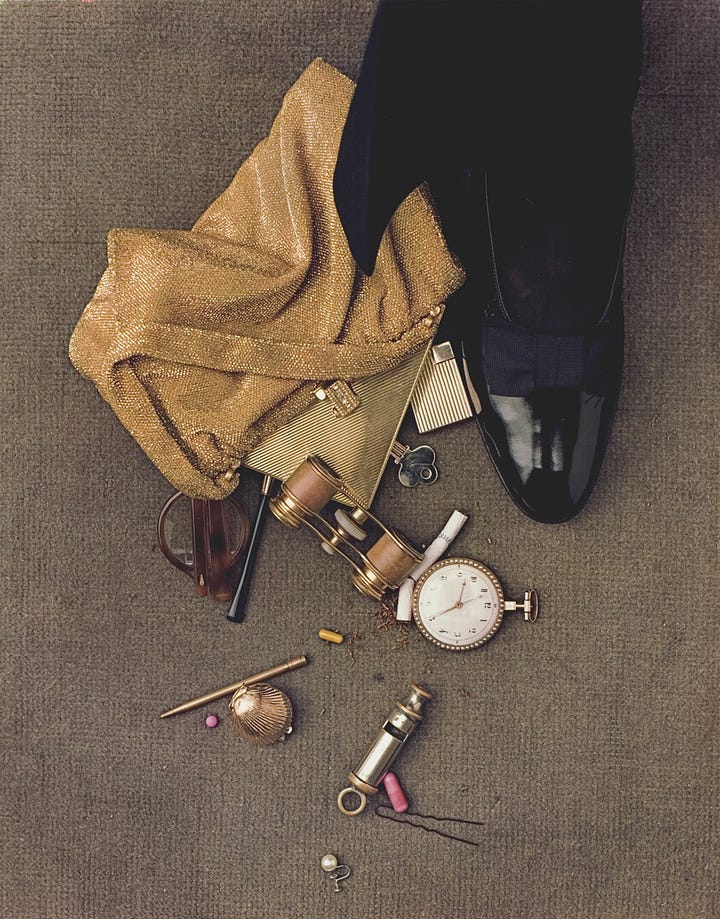

BETH SCHACTER: I absolutely can – it is Irving Penn’s photograph of a spilled purse that he did in 1947 called, helpfully, “Theater Accident”. It was a photograph for a magazine, to sell a whole bunch of products, and the picture is so modern – torn broken cigarette, a fuzzy pill. Just this beautifully framed vision of a woman’s bag spilled open as she rushes to get to the front of the line between acts. It was at the Met in their exhibit about advertising. I’ve become one of those New Yorkers who goes to the Met so often, I don’t feel like I have to see anything, so I end up seeing these smaller pieces.

BS (cont’d): Oh, and I also saw this incredible Swiss painting called Isle of the Dead by Arnold Böcklin. It was a commissioned painting by a widow and Böcklin painted this coffin into the painting being ferried to the Underworld. When he delivered the painting, he said “You will be able to dream yourself into the world of dark shadows.” I’m just finishing Clancy Martin’s “How Not to Kill Yourself” and the idea of dreaming yourself into the Underworld hits hard. I’m not morbid, but I am really thinking a lot lately about how we talk about grief and death. And that painting was so shattering. It’s in one of the Degas hallways, and I think I passed it a bunch.

CH: I know Isle of the Dead in particular very, very well. In fact, I’m developing a project related to it right now. It speaks to me for all the reasons you just described. Most of my family is dead at this point and I recently became the eldest member of it about twenty years earlier than my father did, which is…surreal. I’m only forty-eight. Needless to say, grief and death and how we talk about it – how we treat it as a culture, in our art – is endlessly on my mind.

BS: Oh wow, do I understand this – I lost my mom when I was younger, before I was really a writer for a living and I think a lot about how it feels when you don’t really “become” before they leave. Like, it doesn’t count in some sort of way? Which I know isn’t real, I know it isn’t true, but it feels real? And I think a lot about the sadness of wanting to close your eyes and be taken to the island of the dead. How grief can make you want to visit a land you’re not meant for yet. And I do believe – truly as cheesy as it may sound – that part of what we do as writers is build little bridges to lands we aren’t meant for yet. The land of death included. And maybe that is the best we can do.

CH: I think you’re right, which is probably part of the broader mission statement of artists, which I’ve always thought is to help people understand what’s happening to them. Not that we have the answers, but maybe we have the right questions. I’ve never articulated it this way before, but I suppose it’s a form of emotional mirroring.

BS: I like that idea… like maybe art is a version of sitting with someone and actively listening. It also reminds me that people bring what they bring to your work which is what makes it relevant to them.

CH: One of the things I oddly take comfort from in Böcklin’s painting is that it was a commission, and yet it feels so deeply personal. He’d suffered a lot of loss in his own life – kids – so, I can only assume he infused the work with some of his own loss. A lot of fine art history is like this, of course, but I do think it’s a reminder that, despite how often it feels otherwise, we can still make personal, very authored art in exchange for a paycheck. Or, at least that’s what I tell myself to help me sleep at night.

BS: Yes! It is also a version of other paintings – the widow saw an earlier version in Böcklin’s studio. He added the boat. To connect with her grief. It is a rewrite, a reimagining. I find that so inspiring that he can think about someone else’s pain and also talk about his own pain. Isn’t that the greatest part of walking that “money for art” line - that you can find something new as you tell a story you didn’t mean to tell?

CH: Indeed. So, let’s talk back story. I don’t know nearly enough about who you were before your life as a filmmaker, with the exception that graduated from Columbia with an MFA in screenwriting. Where did you grow up and when did it first dawn on you that “Yeah, I want to tell stories for the rest of my life”?

BS: Ah, okay, the biography part of this. I grew up in Ohio, Connecticut and New York. I was a horse girl. I didn’t know I wanted to tell stories for a long time. I was pretty lost, and I was also a total coward, so even when it occurred to me that I was practically leaping out of my seat to be up “there” in the theatre, it didn’t occur to me that it meant anything. I figured I would be a producer. Or an agent.

CH: I’d love to hear more about what being a “total coward” meant in this context. I’m from Detroit myself, and I think I was hobbled by fear, too. It took me a long time to accept that someone from a working-class family, first kid in his family to even get a college degree, could do more than talk about how he wanted to work in the arts.

BS: I think it is so easy to think that there’s nothing you can offer – nothing that you can add to the conversation. I mean, the people who were doing it when I even let myself imagine being an artist – who were making Reality Bites and “My So-Called Life” and Say Anything – how do you even imagine yourself standing in a room and saying, “Umm, I have something to add”? It is a ridiculous notion. And I can’t imagine if I was from a non-academic family. As it is, my highly educated family thinks I’m faking this whole career. There’s really no amount of press that can undo the “you work in the arts.”

I think we like to talk about fear and cowardice as a personality flaw. But I think they are gifts. Nothing is brave if nothing causes you fear.

CH: Ooh, I like that.

BS: Eduardo Machado taught playwriting when I was in grad school, and he told his students to “write things that you are afraid your parents will read/see.” Fear, shame, cowardice – they are the necessary states of being to inspire bravery and strength. Don’t run from them.

CH: I think I struggled for a long time before I fully embraced this creative philosophy. How are you doing revealing yourself on the page? Do you feel you’ve been able to sufficiently overcome that urge to run away?

BS: I’m disgustingly good at revealing myself. I would say I’m better at it in my writing than in therapy sometimes. Not me exactly, but what I write has to scratch that part of my brain that needs scratching. For me, the revealing is the answer to the fear – if I show myself, or just a little of my truth, somehow that makes me brave. And when I say it out loud, it makes no sense – how can something scary make you braver?

My first movie – Normal Adolescent Behavior – was about me and my friends. But it was also an adaptation of Spring Awakening. And it was also about how I saw my own sexuality. I was everyone in that story. And none of that happened, and yet all of it was real. Sometimes, it’s just a little Easter Egg of a thing – giving your characters a name or an anecdote. My favorite is when I get those moments in places they absolutely don’t belong. There’s a beat in Season 1 of “SEAL Team” – a show that is not at all reflective of my experience! – that is just something that happened to me. But to tell people what it is, well it sort of ruins the magic trick.

CH: What I find interesting about your answer here, besides the general content, is the language you’ve chosen to use. It sounds almost shamanistic, or maybe just ritualistic – a writerly practice that, through symbols – words – summons a version of you that you’re trying to bring into being. Counterintuitive, I know, because we’re talking about revealing ourselves, but maybe this will make sense to you. I’ve heard many storytellers, in various mediums, say some version of “I write to find out who I am,” but my experience is that writing also creates who you are. The act of creation is two-way, I suppose I’m saying. Does any of that ring true for you?

BS: I haven’t thought of it like that. I guess I understand it – but would clarify to say that I write to wrap my arms around who I am, what I think, how I want to move through the world. Some of it is wish fulfillment – that monologue you say in the shower that comes out perfect, that gets the point across in the way you never could in real life. It is such a small detail, but in Norah Ephron’s script for You’ve Got Mail, Meg Ryan’s character complains that she never knows the most cutting line to say at the exact right time. Until she meets Tom Hanks, and then suddenly she’s Dorothy Parker. For me, writing is a little bit of that transformation – you can say the right thing at the right time, to the right person. And then you can control their response.

So, to answer the original question, writing is how I exert control over the world, in a way that makes me feel some satisfaction that is denied all of us in real life.

CH: Getting back to your backstory. So, what happened after you decided a life in the arts – as a producer, agent, a non-artist I guess you’d say – what happened next? I guess what I’m most curious about is, how did that road lead to you becoming an artist yourself?

BS: I went to Columbia, to be a director after working on some indies, and I wrote a script my first year – about the relationship between Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady – and the wonderful Lewis Cole told me that I was a writer and that, if I worked with him, I could be a writer for a living. Sometimes cowardice needs to be met with mentorship. I guess that is what I needed. Lewis – and Katherine Dieckmann – really made me believe I had talent.

And even then, I wanted to be an indie filmmaker. Maybe a little part of me still does. I wrote and directed my 2nd-year feature and sold it to New Line, which sounds like an amazing origin story—

CH: It does.

BS: —but it would be five years until I had a paying career as a TV writer – the strike, the death of films, and the expansion of TV took a minute.

CH: That mustn’t have been easy.

BS: Those were five tough years – I wasn’t a neophyte, I had made a movie. But I also couldn’t get a job. I went back to the theater and wrote a one-act that I directed with a bunch of friends and that got me a TV agent, and even then it was a year before I was a staff writer. And I got hired four months pregnant.

I guess all of this is to say, I have never said out loud that I want to tell stories the rest of my life and maybe that is because I feel insanely lucky to do this job. I love it a lot and I fear if I tell that career how much I want it, it might get annoyed and disappear. That sounded crazy. Oh well.

CH: It doesn’t, don’t worry. So much of the arts feels like there are fickle Greek gods presiding over our fates. We’re all trapped in an incredibly unexciting drama about artists who have to live with the constant fear that their dreams – and the lives they built with them – could be ruined for reasons beyond their control. Also, as I said all that, I now realize Hollywood CEOs are the Greek gods in this analogy.

BS: I love that. Also, weirdly I just read this hilarious tweet or thread or insta – don’t ask –that said that women would wear less clothing if men stopped catcalling. This was obviously a Greek curse – you can see naked women if you can keep your mouth shut. And someone always ruins it. Which is an analogue for our business as well – execs could get all the awards they want if they would just let artists make art, but they can’t help themselves. So, yeah, they are Greek Gods. But maybe they are also the victims of their own hubris. And we’re half-naked women? Like, I like my analogies, but this one is off the rails.

CH: [Laughs] I feel like we’re on to something here with this!