Q&A: Producer Ted Hope Wants a New Indie Revolution

From shaping the Nineties indie film movement to helping Amazon break into features, the producer has seen and done it all, he has despaired, and he is here to tell you there's hope...no, really

There has never been a bleaker, most soul-crushing time to aspire to make films or television series in Hollywood or most places around the world. The market has been warped and ruined by streamers (and Big Tech in general) and corporate mergers in myriad ways, amongst them the desolation of the theatrical experience, a tectonic and often career-destroying shift of wealth from artists to their employers, and the near-death of original stories. Everyone except those doing the profiteering agree a revolution is desperately needed, but it’s been close to four decades since the last one kicked off — America’s independent film movement of the late Eighties and Nineties — born of emerging artists and fledgling producers raised on Seventies and foreign cinema and, more importantly, a DIY and fuck-the-man-as-you-do punk aesthetic. The landscape is very different today, and I spend most days despairing for film/TV’s future because of that. But I’m not ready to give up yet - and neither is indie film producer Ted Hope.

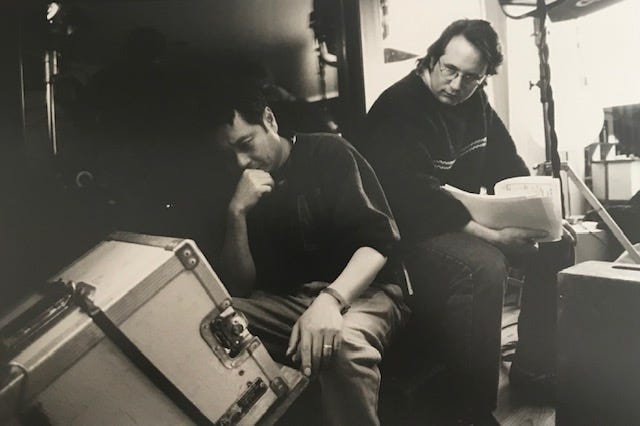

Ted was there at the start of the indie film movement so many of us grew up on and were inspired to become filmmakers because of. He and James Schamus co-founded Good Machine together, a production/sales company that had a hand in gifting numerous classic films of this era to the world including The Wedding Banquet (1993), The Brothers McMullen (1995), Happiness (1998), The Tao of Steve (2000), In the Bedroom (2001), and American Splendor (2003). The company had a hand in cementing the careers of writers/directors as varied as Todd Field, Michel Gondry, Nicole Holofcener, and Ang Lee. Good Machine was ultimately sold to Universal Pictures in 2002; it was then merged with USA Films and Universal Focus to form Focus Features. Since then, Ted has continued to produce; in total, his films have received twenty-five Oscar nominations and six wins. In 2015, he joined Amazon Studios as its Head of Production for Original Movies; in 2018, he became its Co-Head of Movies. Amazon was a valiant effort to resurrect the indie film spirit inside a streaming juggernaut, the results of which I’ll let him discuss himself. He left the company in 2020. Most recently, he produced Cassandro, the first narrative film from Oscar-winning documentarian Roger Ross Williams, and Invisible Nation, a documentary about Taiwan directed and also produced by Vanessa Hope (his wife).

As you might notice, Ted is not necessarily an artist himself — which might make him seem like an odd fit for my artist-on-artist conversation series — but I’ve recently decided to expand my arts chats to include important, daring, and confrontational thinkers on the arts. In Ted’s case, I certainly wanted to hear about his past and part in so many films I love, but I was maybe even more interested in his dissonant optimism for the future of film in particular. Here at Substack, his newsletter

is a constant font of…well, the title gives it away. Hope in the darkness. While I wanted to simply trust his arguments because I needed to believe them for my mental health, I am an inherently untrusting person. So, I asked Ted if I could dig into them from my own perspective, ask some direct questions others might not, and try to get to bottom of whether there really is hope for a renaissance of independent cinema in America.Ted is endlessly optimistic, and it’s contagious. But more importantly, he has the credentials to back up that optimism. So, read on as he and I reminisce about how much fun making independent films was in the Nineties was, how the indie film dream died, and what we’ll have to do to bring it back to life.

COLE HADDON: Ted, I’m going to start this conversation with a question about something that has absolutely nothing to do with lost hope, or hope in any form, or even the state of cinema and the arts – although maybe it will, let’s see. I just want to know your theory as to why The Myth of Fingerprints, a beautiful, painful independent film from Good Machine that has haunted my memory for nearly thirty years, has been consistently unavailable for years? I used to own it on VHS, and now I regret binning it when VCRs went the way of the dodo.

TED HOPE: I just checked and you can order a used DVD for $37 here in the States on Amazon, although it doesn’t look like it is available for streaming or VOD in the U.S. It’s funny because we made that film for Columbia-TriStar home video. That company — and their financial support — was responsible to a large degree for the late Eighties and early Nineties American Indie film scene. They funded so many films, but that was the only one we did with them. I think Myth was also the film where James Schamus and I both decided we should stop taking credit on the Good Machine films that we didn’t really work on.

CH: Why was that?

TH: We realized that although we had started the company, it was no longer just our show. We each took executive producer credit on that film, but thereafter only took individual personal credit when we were truly instrumental in either getting a specific film made or shaping it. Mary Jane Skalski was the producer at Good Machine who made Myth happen, and it was she who helped it become what it was, and certainly not me. Up until then, though, we were still thinking that it was “our company” and, thus, we were deserving of credit on the individual movies we made, as it was the company structure that allowed all of us to support that film. That is a mistake — over-emphasizing my or our — individual contributions to a film I made a couple of times in my career and needed to learn to recognize better when to give up the reins. Frankly, it bugs me, this current trend of crediting all the individuals at production, sales, distribution companies in the film’s credit. I think it is overreach. Those people have steady jobs and it is their responsibility to support those films. Personally, I think end credits should be reserved for those whose main focus was on that film.

But back to your initial point, although I certainly don’t miss the clutter that VHS and DVDs created, I really miss home video as a thing and think we all lost something big when we gave up discs and tapes for convenience. I loved seeing this past year that the Blu-rays of Oppenheimer sold out almost immediately.

CH: It’s such a small victory, but I whooped inside, too.

“I think any corporation that either funds or acquires a film should take on the contractual necessity of making sure the film can readily be available anytime anywhere and in the proper context.”

TH: Our love for any experience is enhanced when we have that something to hold onto. It doesn’t have to be either/or. It can be both/and. I have never thrown out my DVDs, but I did give away most of my VHSes. I had to learn the hard way, throwing out and replacing my vinyl several times over. Your desire to be able to access Myth also highlights how we filmmakers have yet to be trained or develop the Best Practices necessary for successful archiving, preservation, and future-proofing. It really should be part of every filmmaker’s toolkit. I think the global support organizations should take some responsibility and try to instill better practices into filmmakers. Applications for festivals should embed preservation strategies as a requirement.

CH: That’s a brilliant idea.

TH: Personally, I think any corporation that either funds or acquires a film should take on the contractual necessity of making sure the film can readily be available anytime anywhere and in the proper context. But that’s a much longer conversation. Yet, since you raised an issue that highlights a problem, isn’t it always our responsibility to offer a recommended course of action? If not, can we make it so?

CH: Indeed, but one of the challenges of that responsibility is that not all of us possess the expertise to offer such recommendations – which is one of the things I love most about your Substack and just reading you in general. It’s also one of the reasons I wanted you to join me for one of my conversations so much.

TH: Thanks, but I disagree.

CH: Really?

TH: Expertise in such things is overrated, and particularly in both art and commerce. We all know how we feel, be it from an artwork or business practices. We get a feeling if something is driven by passion or just to make another transaction. We know if it is set up just as a financial endeavor or if it is driven more to make a deeper more complex connection. There are business interests that don’t want us to voice dissatisfaction or irritation, but the willingness to resist the status quo and aim for something other than that is where a lot of great art is born. I just think everything progresses faster and towards an optimum result when we are all comfortable making suggestions – particularly when we are able to do it with humbleness and consideration. We don’t need to be right. I love to be proven wrong. I am always looking for the better way, and I suspect it is more often found by those that come as true innocents – true innocents who have learned to listen and observe.

CH: It’s an approach not dissimilar from what drove the explosion of independent film distribution in America, no? “True innocents” revolutionizing from that perspective rather than outdated ones. But I am surprised by the suggestion that some expertise — or maybe experience is the better word — to inform such recommendations. I’ve been surrounded by film/TV people for more than fifteen years now, on multiple continents in multiple markets, and I don’t think I’ve met more than a handful who can speak as intelligently and cogently about independent film, film distribution, or the like as you do. Frankly, you’re one of the few people who inspire anything like hope in me in this industry – though that’s a subject we’ll get into more later.

TH: Thanks for those kind words. I care. And I am fascinated. What we make is determined by how we make it and where we make it. All of it is intertwined. But it gets challenging when it seems like everyone is focused solely on their projects, and you can see how it brings it all down with it. We are so focused on production, on getting it made – but if we invested time in infrastructure and process, it would lift everything up. But I get it, too - I just want to get my movies made well, in a manner that rewards all fairly, and then released in a way that allows them to have the impact they deserve. In some way, our love for the making of films destroys their chances to really connect deeply with audiences.

“In some way, our love for the making of films destroys their chances to really connect deeply with audiences.”

TH (cont’d): I suspect that ninety percent of everyone who enters or ever entered this business did because they loved movies and in some way were changed deeply by them. But they start to forget at what altar they worship. We don’t have much of a social welfare net in the States. We don’t do much investment in the common good. We encourage competition over cooperation. We are raised to think someone should be on top or that someone is better than someone else. It is disgusting. But it gets under our skin. Most folks dream of family and home. It’s quite common to want those things and how the hell is anyone supposed to afford it – particularly if they went to college and accumulated debt. How can we expect them to prioritize the art, the aesthetics, the emotion or the mission? I worship at the altar of art. I find my engine in my devotion. My gasoline and my match. I appreciate your kind words, Cole, but I have been incredibly fortunate to luck into some good situations and avoid most of the bad ones. Seriously.

CH: Let’s properly start our chat by looking backward to contextualize where you — and cinema — are today. Can you talk about those early days at Good Machine, but, really, about the explosion of independent film that we now think of as Nineties Cinema? Who were you, what was it like to be there at ground zero, and how much fun was it? Please tell me it was fun.

TH: I had just started producing movies, having done two with Hal Hartley, and was getting the work-for-hire gigs as a script reader, assistant director, production manager, and line producer that gave me enough confidence to think that movies could be a career. Making movies was all I really wanted to do with myself. I was willing to sacrifice everything to make it happen. Most critically, though, I didn’t feel the existing models of a producing career that I could see were appropriate for me.

CH: What about them didn’t make sense to you?

TH: I didn’t want to partner with just one director. I wanted to learn in a different way and go deep in a different way – not just how to help one director excel at their work, but how to do something that was replicable for multiple filmmakers of all sorts. I had done some community organizing and political campaign work previously, and felt you needed to create a regular cadence of “success” in order to actually benefit from it. The industry needed to see you as a regular supplier who delivered a consistent quality.

I was always looking to find ways to make 1+1=3. I built lists of directors and producers whom I thought I could collaborate with. And the fortunate thing was that I wasn’t alone in such thoughts. Not even close! NYC in the Eighties and Nineties was flooded with folks like me who wanted to make a different sort of cinema, different from Hollywood, and informed by the art house “authored” cinema from the generations before us. The cultural events in America and New York also shaped us. Punk rock had delivered a DIY attitude that helped us all not wait around for permission or ever aim for perfection. The AIDS crisis made it clear once again, for everyone, that the government and society would ignore people’s needs if they could get away with it and that, of course, life was very fragile and easily lost. People were dying. People close to us – from our friend circles.

CH: In so many ways, what you’re really describing is a community.

TH: One hundred percent! There was both an urgency and a camaraderie that extended to everyone just by being there. I am also always looking for new ways that we — as communities of all sorts — can be brought together. That, of course, was where my initial enthusiasm for social media came from, even though it led to something completely different. It’s the thin little silver lining within every social crisis and movement, every war and act of oppression and prejudice. They require action, for people to say, "I am mad as hell and I am not going to take it anymore.” We are never alone, and we have to stand up and push for the things that matter to us. You start to search for new ways of doing things and in the case of cinema, technology was creating new ways to make, collaborate, and distribute work all over the place.

Back in the Nineties, I could make movies on the cheap, and they were needed, and people were hungry for new perspectives. Indie film support was just being built. Talk about a lack of transparency - in those days you couldn’t get your hand on a budget, a schedule, or anything that might help demystify the system we were in. As hard as that was, it was also unifying and gave us a mission. We were going to solve it together!

When I look at the legion of leaders that came out of Good Machine, I think it has a great deal to do with the fact that people felt they belonged, felt they and everyone around them — for the most part — were in it for the right reasons. They mattered, and they were part of something bigger than themselves. We made a lot of good films for sure, but we also gave a ton of folks the opportunity to show they could make a huge difference in the way things worked.

Fun, though? Yeah. It was always fun. I was working with people whom I admired and really enjoyed hanging out with. And I was doing what I loved. It was how I wanted to use my life and labor. I criticize myself now for being too accomplishment-based, but I still consider myself a hedonist at heart, albeit one who most loves to get great work done despite all the sacrifices it requires. Not everyone likes to be responsible. A producer is working for everyone involved in the movie you are making. Frankly, I think it even goes beyond that - we are working for everyone who consumes or generates culture of any kind. I feel I am serving everyone, and I know that not everyone finds that responsibility fun, but I have always. You want to build a tree fort? I want to plan it and build it and not wing it. You want to meet up at the park for a game of ball? I want to make sure enough kids show to make it fun.

I grew up in what was once a rural area, and it meant to have fun, you had to be organized. I learned how to make things happen, and it is generally pretty fun to do what you are really good at, and I got good at making things happen. I still find that fun. Although, I don’t think it is anywhere as close to as welcoming now as it was then. If you showed up to the party, you were invited in and given something good to do. Just pick up that guitar, kid, and sing. Jump around a lot. You are a fucking rock star! Boom.

CH: Before we move on, I find that many periods of my life are tethered to very specific moments. Touchstones. A place I inevitably shift back to through time, and which makes me smile, even makes me feel like home. Is there a specific moment from the Nineties that is that for you? Where in your mind, then and now, everything was as it should be?

TH: I so remember starting Good Machine and putting my soul into it. My girlfriend had left me and all I wanted to do was work. I had pitched the idea to two friends, and they both said yes. I eventually committed to James Schamus - and when we both got films into Sundance, he convinced he was the one that should go and I should stay behind and do the accounting. So, there I was working away late at night when Ang Lee walked in. Soon, and in the midst of a strike, we had three films going. We delivered those and soon launched Ang’s The Wedding Banquet in the heat of the summer with half the funds we needed. I can go on and on about that film and how it changed our company, but all of it was fun for me. I loved making it.

CH: It’s a brilliant film, so I’m glad to hear it.

TH: Really, all we did at that time was about the movies and not the money. The people who joined us were all inspiring. Everyone was in it for the right reasons and gave their all. The team has stayed close ever since.

I also remember getting to Cannes with Hal Hartley’s Simple Men. It was my first time. I didn’t quite understand what it meant, but I loved every moment of it. Even when one of the actor’s agents pushed me out of the car that drove us three blocks to the Palais. I loved it. I think it was the first time I wore a tuxedo. Getting totally drunk at Le Petit Majestic. Loved it. Playing catch with a Steak au Poivre with our DP, Mike Spiller, and spraining my ankle. James wheeled me home through airport security, and I’d never got through the airport with that kind of speed thanks to the wheelchair. I loved it all.

CH: I hope we get to do this one day in person, so I can ask you even more questions about the Nineties and everything you’re describing. It feels like such a fantasy compared to the industry I broke into in the aughts and the one that has evolved during the first two decades of this century. I’d love to ask about the decision to sell Good Machine in 2001, which feels inevitable in hindsight. Every indie was doing so. But I’d like to hear you reflect on your own part in that decision and how you feel about it today.

“They reduce our love to a transaction.”

TH: It was fun. Creating and building things together with others is always fun in my opinion – but there are those who hate that and don’t want it to be so. We create so much of our own pain and misery. But don’t get me wrong, making films is really hard work - yet we are generally then using our labor in service to something we love, so that can never be bad. That passion, though, is the pain in life - we collaborate with those who see the results as just another product or piece of the chain. They reduce our love to a transaction. That is never going to feel good. We think we are doing something that defines the essence of life, and they see it as a way to make a buck.

CH: It’s an exhausting reality of the business, but I will say, I appreciate how you describe this experience – “They reduce our love to a transaction.” That’s exactly it.

TH: I was speaking to a friend of mine who started an indie rock label around the same time that we started Good Machine. We were laughing at how both of our endeavors were the opposite of a career strategy. We each initially gave it two to five years at best. It was supposed to just be a fun adventure. Like most things, our goals changed along the way - we realized we could accomplish more than we anticipated.

The initial driver for Good Machine always remained the same – to make ambitiously authored work, while trying to find the best business model for such films. As I just mentioned, I can now look back and see how those two components are always creating friction between themselves. They can never be stable and yet business thrives on predictability and replicable processes. It is a delight when both sides align and that was the Nineties for American independent film. As we entered the aughts, the balance had shifted. U.S. distribution was the driver of international sales. To make that business work, it felt like you needed to have U.S. distribution in hand. Although it was possible to still go film to film and place each movie with the right U.S. distributor, that was a challenging process. Chasing the highest bidder sometimes was just not worth it - it brought too much friction with it. We realized after we had to distribute Todd Solondz’s Happiness ourselves that we needed to enter the distribution field somehow.

Meanwhile, I had some personal concerns with growing the company and the responsibilities that came with that. We were starting to have to chase upfront fees as the priority. I like to bet on myself, which can pay off well when you are right, but if others are dependent on you for their salary may not be the way to go. There’s a lot of risk to that game, and their jobs and welfare are on the line.

CH: This is all so fascinating. Please, keep talking.

TH: I came to realize that I most wanted an environment where I was free to say “yes” despite the realities of the world or the business needs of the company. If you are looking for reasons to sell, having your partners wanting a bigger sandbox while you want to get really small is a pretty good one. Having suitors is another one. We got asked to dance about eleven times in all I think - we had something good, folks wanted in on it, but they rarely valued it as well as we did. It wasn’t so much the money - but that was still key. We all wanted the chance to do what we did well, even better. We got to truly weigh how important autonomy was for each of us - and to me, that was virtually everything.

At this moment in time, I am thrilled I’ve gotten to do all I have professionally. I keep learning, testing myself, and discovering new things. All of us want to apply all we’ve learned in a manner that does that, but opportunity is rare. No one really comes a-knockin’, asking how they can help you put what you have to offer to work in a manner that is rewarding. You have to strategize what that is and how it can happen. You have to engineer your own serendipity. The circumstances are rarely going to be right, but when they are, you can’t blink. You have to leap, even if you forgot to pack a parachute. It almost requires you to have a whole suite of plans, well thought out, waiting for the right accumulation of factors to align in order to take real action.

“No one really comes a-knockin’, asking how they can help you put what you have to offer to work in a manner that is rewarding. You have to strategize what that is and how it can happen. You have to engineer your own serendipity.”

CH: When you look back, how do you emotionally process the demise of the indie film movement you helped shape? Myself, I think I had hoped back in the mid-aughts that you and your peers would…I don’t know…inherit Hollywood in some way. Be absorbed, sure, but take it over in the end. Maybe become “the man” in the process, but still shake things up like happened in the seventies. Obviously, that didn’t happen.

TH: [Laughter] I wish it was like that. It was in some ways, but yes, it is its own thing too. Many of the directors who are considered the top filmmakers today came from indie, be it the Nineties or the waves and ripples that followed. Producers and executives are another story. I think in some ways, it is a question of how content one is with doing what they do. Killer Films has two films in the Oscar race this year and they have never deviated from what they do so well. They try on new models. Toe dip. But they stay focused on getting the films they love made. Period. But they are really one of a kind.

CH: Those two — Christine Vachon and Pamela Koffler — are two of my favorite producers, if not my outright favorites. As you say, they’re really one of a kind.

TH: Most people are the frogs in the warm bath not knowing the world is increasing the flames. Change never occurs until the pain of the present outweighs the fear of the future – and a warm bath always feels soooo good, right? You then add to that the fact that the powers that be will never address building a better process or better product when everything is perceived as “good enough” and, as a result, none of the necessary operational improvements will be addressed that would keep the culture relevant for the new generations. They can make more money easier deploying their capital elsewhere. I think “indie” fell into this trap.

CH: How so?

TH: We did not agitate enough to push for what could have been our true moment and the culture and business leaders did not want us to. The door closed, but I think there are openings again. In the seventies, a cultural revolution was needed, but from the 2000’s to now, it seemed perfectly fine to enjoy the warm water to most in the field - or pool. I had the personal goal when I got hired at Amazon to establish what was referred to as “prestige” an irrevocable part of the studio’s identity. For all it mattered to me, it didn’t matter to most others there, and since I failed to persuade them, it was clear to me it was time to leave.

CH: Okay, let’s tackle the question I’ve most wanted to ask you. It’s 2024 and American cinema is…not in a great place. You might not agree with my verbiage here, but the sentiment is, I think accurate - the studios have fucked the business up, the streaming model is, for the most part, not producing the zeitgeist moments that movie theaters used to give us every weekend, and there is an overwhelming sense of dread everywhere I look within the industry about the future. I know we’ll inevitably talk about potential fixes, as you suggested is our responsibility earlier, but before we get into how things might turn around, what I want to know is this: being part of what you were in the Eighties and Nineties, the indie ventures this century…how do you not wake up every day and despair at the state of things?