Q&A: Screenwriter Jed Mercurio on 30 Years of Thrilling Audiences

The creator of smash hits 'Line of Duty' and 'Bodyguard' reflects on what he's learned from his many triumphs - and failures - in British television

There are few screenwriter’s names as big as Jed Mercurio’s in British television. For thirty years, he’s been turning out series that grab you by the scruff of the neck, lead you into worlds you thought you knew, and then shout, “There, you see the truth now - don’t look away!”

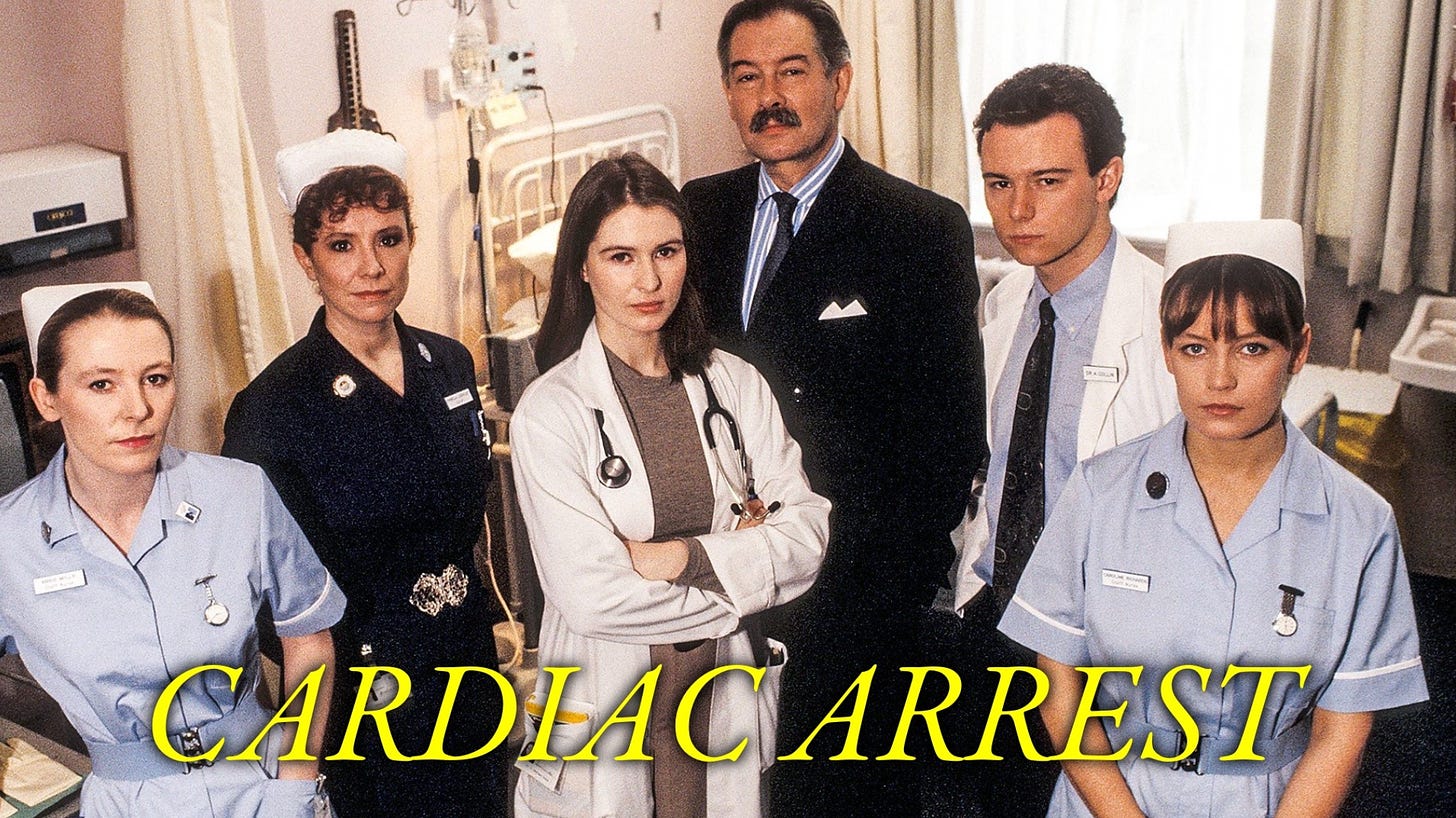

Jed’s journey as a screenwriter began, almost by accident, when he created “Cardiac Arrest” for the BBC in 1994. The series was inspired by his own career in medicine and revealed a darker side to the life of hospital doctors in the National Health Service (NHS), dispelling decades of popular myths perpetuated by gentler dramas and sitcoms. It was an instant success. Jed followed it up with other series less topical — and certainly less controversial — but it wasn’t until he adapted his debut novel, “Bodies”, that he scored his next serious hit. Again, he took on the ugly underbelly of the medical profession. Next time around, he set his sights on corruption in the Metropolitan Police with “Line of Duty”, and six seasons later, audiences are still clamoring for more of Anti-Corruption Unit 12. More recently, Jed created the global hit “Bodyguard”, which made the government’s anti-privacy pursuit of the war on terror the target of his ire.

All of these series are both wildly confronting and wildly entertaining, which is why I’ve chosen to focus on them and what has made them so successful during this artist-on-artist conversation with Jed. He has cracked the code of turning personal convictions into critically and commercially successful art. The two of us are about to go in-depth into the mechanical aspects of his craft, the philosophy behind his storytelling, and the background that underpins his intense work ethic. But with all of these triumphs, Jed also sees many failures, which we’ll discuss in detail. He’s learned a great deal from his three decades as a TV creator and showrunner, and I hope what I steer him toward talking about is helpful to you on your own creative journeys.

For screenwriters at all levels, I would focus on Jed’s story-first approach to creating his series, whether he sees his work as acts of protest, and how he has come to measure (or not measure) a series’ success.

COLE HADDON: Inspiration comes in all different forms for artists, but I want to start by asking where you look for it outside of your art. What I’m getting at is, what brings you joy — physically, spiritually, both — beyond the laptop screen and the wrangling of ideas and words into stories?

JED MERCURIO: Inspiration, for me, is a work process. That means, when I’m in that state of mind, I’m actively looking for ideas in the real world or in other art forms. It’s a conscious process. I have to decide to do it in the same way it’s an act of volition to sit down and write the next pages of a treatment or a script. Outside of that process, I play sport. I had to give up football a few years ago when wear and tear made it more about fear of injury than about fun and goals. Now, I play tennis and golf. I like being outdoors and doing something physical. I also like the technical challenge. There are things I can work on or think about in an effort to do better.

CH: Do you look for that same kind of technical challenge when it comes to your storytelling?

JM: I do regard writing as a technical process. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a writer who slavishly follows structure theory dogma. I’m pretty skeptical about script gurus who claim to have unlocked the secret structural code common to every hit movie. I don’t even think about structure in a formal sense, to be honest. But I do give careful consideration to the building blocks of storytelling by applying a calculated thought process to shaping the essential components like goals, jeopardy, mystery, etcetera.

Also, I’m a showrunner. On nearly all the scripts I write, I’m the creative leader of the project. In collaboration with a production team, it’s going to be my responsibility to realize the ambitions of the work, so when I’m writing, I’m also weighing the technical challenges of putting the action on screen. From experience, I know you have to break everything down into filmable components.

“I start with story. I need to know the subject, setting, and premise before I consider character design.”

CH: Let’s spend a moment on your use of the words “building blocks of storytelling”. In the U.K., there’s a religious obsession with the concept of “character first”. Everything’s “character-driven”, which is fair – character drives most great stories. But whereas you say you don’t slavishly follow structure theory, many seem to do so when it comes to characters and that can often be to the detriment of the storytelling itself – not to mention the audience’s experience.

So, let’s start there. Do you know every element of your characters worked out before you start writing, so that they drive the action wherever it goes? Or do you create character types and then pit them against your “technical” machinations to see how they react and ultimately, through that crucible, reveal who they really are to both you and the audience? Or, hell, some other approach altogether?

JM: I start with story. I need to know the subject, setting, and premise before I consider character design. The character must have attributes that render them suitable to serve as the protagonist and specific flaws that will be exposed the challenges they face. My process is a continuous feedback loop between the two - how does story shape character, how does character shape story? And in thrillers, you have to pay a lot of attention to the villain’s plan. Usually, that’s what gives forth the inciting incident that propels the whole story.

CH: You’ve described your writing as a technical process. You used the word “calculated”, as well. Your story and characters interact in a kind of mathematical ballet as you develop, it sounds like. Once you start writing the script, is there much room left for surprise at that point? And by surprise, I mean for you, not the audience.

JM: I constantly encounter unforeseen problems. Naturally, these come as surprises, as I’ve generally tried my best to do a decent job of the storyline!

Sometimes I reach a point of sniffing out the character’s decisions as unbelievable. Often it’s all about making sure a character has a healthy level of skepticism about the intentions of the people around them. They stubbornly resist being led through the door beyond which the next chunk of plot lies. Another fairly frequent discovery is that a section of the script is nowhere near as interesting as it appeared in outline form. I feel the tension deflating scene by scene. I need to figure out a new event to give the story a kick up the bum.

CH: Alfred Hitchcock was one of the great titans of the moving image. Almost every film he made was both deeply personal and engineered to manipulate his audiences. As he first called it – cinematic. So many of your TV series seem, at least to me, to be as carefully engineered, which I hope you receive as the compliment I intend it. You tell these great stories, filled with twists and turns that constantly titillate and shock and surprise and keep audiences on the edge of their seats. Where does your audience fit into your creative process? How conscious are you of them as you construct your quieter, more emotionally thrilling stories and, of course, your bigger rollercoaster rides?

JM: My perception of the audience has changed over the years.

CH: How so?

“I imagine the audience watches their favorite TV show the way I did as a teenager and still do now - with their full attention, absorbing every plot nuance and nugget of subtext.”

JM: At the start of my career, I was pushing back against executives who characterized television viewers as inattentive. One executive cautioned me against making my plot too complicated as I had to remember most viewers aren’t even concentrating on the program – “It’s playing in the background while they’re doing their ironing”. Another claimed that the mainstream audience couldn’t remember anything that had happened in a previous episode of a series. I’ve disregarded those cynical misperceptions my whole career. I imagine the audience watches their favorite TV show the way I did as a teenager and still do now - with their full attention, absorbing every plot nuance and nugget of subtext. For most of my career, that idealism led to broadcasters positioning my work away from the primetime mass audience. After “Cardiac Arrest”, pretty much everything I did aired in niche slots until “Line of Duty” made the jump from BBC2 to BBC1 in its fourth season.

JM (cont’d): Technology has played a big part in TV executives coming round to my way of thinking. Streaming enables viewers to go back and replay scenes they don’t grasp first time around and binge-watch episodes so that serial storylines and Easter eggs land clearly.

Another important development in recent years is the breadth of audience research. We know far more about how people watch TV. I can look at data that tells me whether viewers stuck with an episode the whole way through or drifted away, I can see what proportion of the viewership tunes in for the next installment, and so forth. The psychological/emotional experience of watching remains subjective and therefore stubbornly refractory to measurement, but the viewing figures themselves are cold, hard facts. When you have a show that’s watched by millions of people, you also get a pretty chunky sample size, which massively improves statistical reliability. You know whether you’re broadly getting it right or broadly getting it wrong.

Of course, none of the above is available to me when I’m writing the script. I only know I’ve succeeded or failed when it’s too late for me to do anything about it. They say in medicine that experience is the quality you’ve gained just after you most needed it. In scriptwriting, I can only weigh years of experience of what has worked and what has failed to guide me, and, even then, I don’t know for sure, because a show changes over time, as does the viewership and their viewing habits. I wish I had a sample size of millions to guide me on how effective a twist is when I write it!

Instead, I rely on a sample size of about half a dozen people who work on the show as producers, directors and script editors, who give me their honest feedback. I’ve been fortunate to work with some excellent collaborators and my work wouldn’t have been nearly as successful without them. Occasionally, I’ve rejected their consensus and plowed on regardless.

“In scriptwriting, I can only weigh years of experience of what has worked and what has failed to guide me, and, even then, I don’t know for sure, because a show changes over time, as does the viewership and their viewing habits.”

CH: I just compared your storytelling, in a manner, to Hitchcock. But I’m curious what storytellers, in any medium, you count as influences on your style and creative imagination?

JM: I take any comparison to Hitchcock as a huge compliment, however unjustified!

The biggest influence on my writing is still the TV I watched growing up. I want to recreate the kind of plot or character beat that still lives with me forty-odd years after I first experienced it. “Star Trek” and “Hill Street Blues”, basically. The best line of dialogue ever written is, “Beam us up.” It sounds like what they actually would say. I was privileged to work with Steven Bochco on a couple of pilots - sadly not picked up to series.

CH: I’ve heard wonderful things about the man.

JM: He remains to me the archetype of the showrunner - smart, funny, self-effacing, collaborative. He always wanted us to do one more pass on the script. He always wanted to talk through a plot point one more time. He was always looking to achieve the best result possible, and he knew the only way was through hard work. One of my lasting memories is the two of us sitting in the lobby at HBO waiting for a meeting and chewing the fat about “Hill Street Blues”. Me going full fan boy about minor characters in the show and Steven laughing when he started to remember characters and jokes he’d forgotten. The police stations in “Line of Duty” are named after ones featured, but usually never seen, in “Hill Street Blues”.

CH: I hadn’t realized that.

JM: When we shot Season 4, I texted him a photo of Polk Avenue Station and he replied, “It exists at last!”

CH: Returning in a roundabout way to the subject of inspiration, your life as a hospital doctor inspired your first foray into television, “Cardiac Arrest”, which I’m a great enough admirer of that I own it as a box set. But when I read about its origins, so often the language others use fixates on how you answered an ad for a medical adviser for a TV series and ended up creating a medical TV series of your own – with no previous ambitions of writing. I want to dig into that because something about this smacks of professional mythology, the kind that builds up around artists. What was your relationship to writing and storytelling in general before “Cardiac Arrest”?