Q&A: Gennifer Hutchison Talks Breaking In, Breaking Bad, and Keeping Things Grounded in Genre

From meth kings to LORD OF THE RINGS: THE RINGS OF POWER, the screenwriter has learned a thing or two about crafting character-driven stories within epic narratives

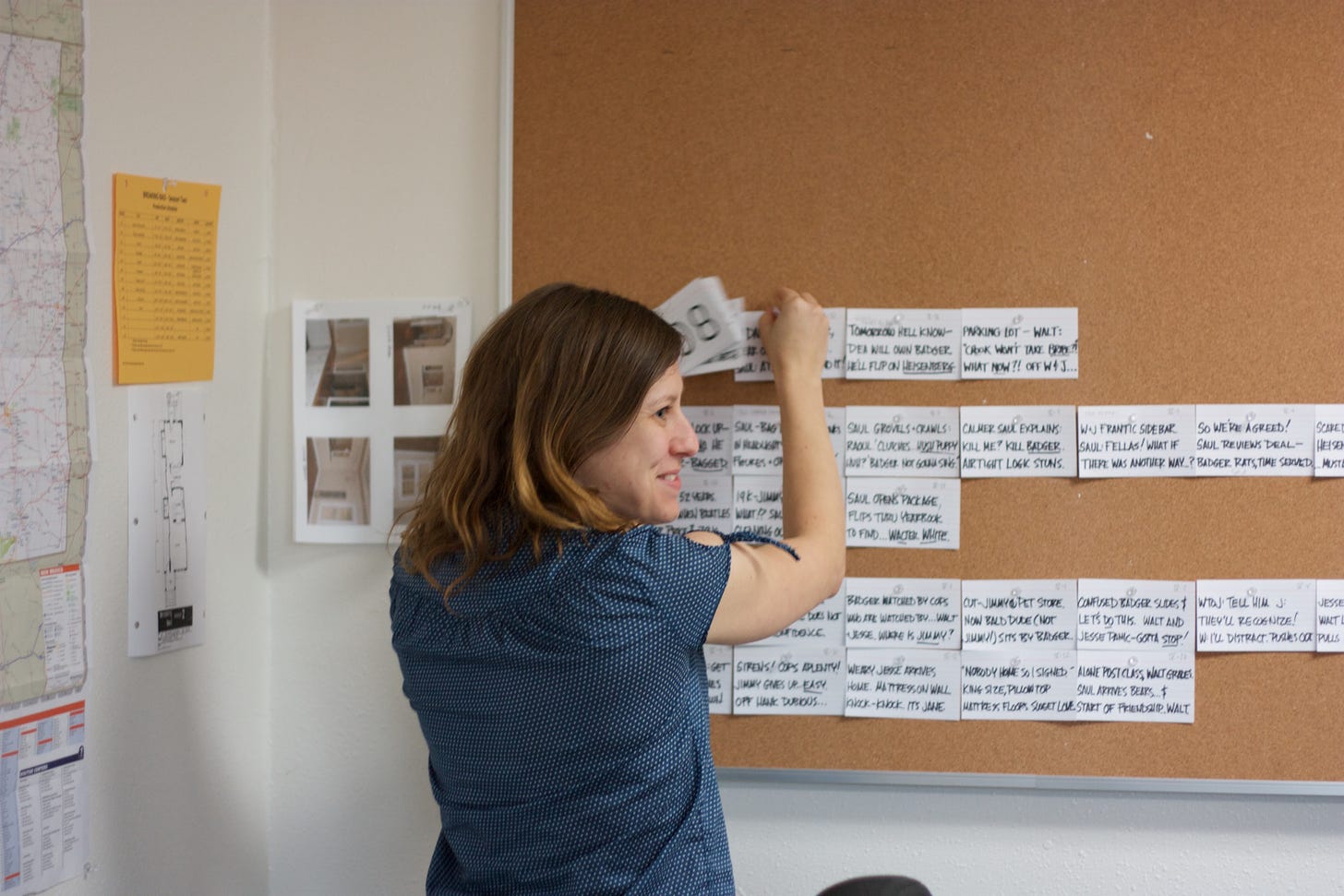

If you’ve never had the pleasure, let me introduce you to Gennifer Hutchison. The television writer got her biggest break after joining the writers’ room of “BREAKING BAD” as a writers’ assistant. She’d been doing the hard slog as an assistant for years by this point, but, while working in Vince Gilligan’s nascent crime universe, she was able to graduate to staff writer by the third season and, by the series’ conclusion, score her first Emmy nomination and win a Writers Guild of America writing award. When Gilligan and fellow “BREAKING BAD” writer Peter Gould decided to spin the series off, this time focusing on shady lawyer Saul Goodman in “BETTER CALL SAUL”, Gennifer joined the new old team. More Emmy and WGA Awards nods followed, but so did a huge title upgrade. By Season 3, she was named Executive Producer. Within a few years, she would go on to join one of the most expensive TV series in history, “THE LORD OF THE RINGS: RINGS OF POWER”, again as an EP.

That’s one hell of a fifteen-year run in Hollywood, as far as I’m concerned.

Now, the mistake here would be thinking these three series aren’t all cut from the same cloth - because they are. They’re all genre epics that work almost entirely because of the character-focused approach to their stories. By keeping the characters’ emotional journeys grounded, painfully human — full of grace and flaws and inexplicable contradictions — the extraordinary nature of each series becomes that much more convincing. This is one of the reasons why I wanted Gennifer to join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations, to help me — and, hopefully, you — better understand how to pull off such intimate stories within expansive narratives and worlds.

For aspiring and emerging screenwriters, I encourage you to pay specific attention to Gennifer’s honesty about the evolution of her writing and career. As you’ll see, one does not simply become a Lord of the Rings overnight. It takes a lot of fucking work.

COLE HADDON: Your professional writing career, up until this point, has been defined by working on and writing what I would call epics – whether we’re talking crime epics or fantasy epics. These are big worlds unfamiliar to most audiences at home when each of the series begins, I mean. But I’m curious if this would surprise, say, your sixteen-year-old self. How familiar would the writer you’ve become be to the one you imagined you would one day become?

GENNIFER HUTCHISON: I think my younger self would be surprised that I wrote for so many years on a crime show and a lawyer show, for sure. Those have never been preferred genres for me, and when I was coming up as an assistant, I always resisted spec’ing standard procedurals.

CH: What was your preference back then?

GH: When I first started leaning into screenwriting — as opposed to prose writing, which I’d been doing all my life — I was focused more on very personal, smaller character stories. I think that’s probably pretty common, though, for folks early in their journey. But I’ve always been a fan of genre — specifically sci-fi and fantasy — so I’ve always loved big worlds, and I pretty quickly started writing my own pilot and feature specs more in those genre realms.

CH: So, younger you would have loved playing around in the world of Middle Earth?

GH: Young me would one hundred percent be completely gobsmacked I’m writing for a LORD OF THE RINGS show. And surprised that I’m working in TV and not directing movies.

CH: I’m going to come back to that directing comment, as well as your prose writing, in a moment. But I want to stick with genre just a bit longer. What about genre excites you most as a storyteller?

GH: The thing that I love about genre is showing grounded characters dealing with those huge worlds and finding the universal emotional truths in those heightened settings. How do normal people deal with gigantic, world-shaking shit? For the shows I’ve written on, I very much always ground myself in the characters. I’m always leading from them so ultimately, I’m still writing those personal, smaller character stories - just in these big world contexts.

“The thing that I love about genre is showing grounded characters dealing with those huge worlds and finding the universal emotional truths in those heightened settings. How do normal people deal with gigantic, world-shaking shit?”

CH: This answer really speaks to me. One of my favorite things about working in genre of any kind is finding these incredibly small, deeply personal moments — often incredibly quiet ones — that only make sense when juxtaposed against all that scope. After all, our everyday world is huge, right? Not entirely dissimilar from, say, Middle Earth. We matter in the context of something so impossibly big and terrifying. When I find them, they can even become the whole reason for doing a project for me, to reveal that one little truth a so-called “grounded” story might not have been capable of.

GH: I love how you put that, and I think you really pinpointed a big part of what makes it special – that even though we’re “small,” we matter in this enormous world. It’s a beautiful way to pair the mundane and the majestic.

CH: Was there a moment in the first season of “RINGS OF POWER” that held that kind of gravitational power for you? That you knew, from the start, was your personal emotional core everything else would ultimately service in some way to move you in some way?

GH: There are so many characters and worlds within “RINGS OF POWER” that it’s difficult to point to one single moment. Overall, I would say that Nori and Poppy’s friendship was one of my biggest emotional touchstones and the first part of the show that I truly sunk into as we started breaking the first season. The sequence in Episode 2 when they pull the Stranger out of the crater and roll him in a wheelbarrow to a hiding spot really became the core of establishing a lot about who they each are, the surface dynamic of their relationship, and the very deep bond underneath it all. The original version was longer and established other aspects of their lives, and while the scenes were cut, I still held them in my head as truths about those characters. I went back to that friendship a lot when grounding myself in the story.

As we built the season, the other key emotional touchstone for me was the relationship between Galadriel and Halbrand. Because a huge deception is involved, I made sure I was always keyed into the pure core of their friendship. There’s truth behind the lie, and staying consistent and tracking that gave an extra depth to the story I loved and that drew me in.

“It’s a huge show with lots of characters, so when I got a bit untethered, I’d always go back to the central relationship for whatever storyline I was in.”

CH: There was so much to juggle, even when compared to something as big as the LORD OF THE RINGS feature trilogy, and only eight episodes to do it in. It was really a hell of a feat without dropping any balls.

GH: It’s a huge show with lots of characters, so when I got a bit untethered, I’d always go back to the central relationship for whatever storyline I was in. I got to establish Durin and Disa, as well, and their relationships with each other and Elrond are really fun and relatable on a core level.

Every one of those stories has at least one small exchange in a scene I wrote that encapsulates a fundamental truth about relationships – both their highly specific one and the universal truths of love and friendships. Being able to tell lots of stories about these complex, often ancient relationships was a big joy of the show for me.

CH: How do you know when you’ve allowed the genre — let’s say the spectacle of the genre, whether that’s magic or exotic murders — to trump those personal, smaller character stories? Is that an instinct you would say you just possessed, or a muscle you’ve honed over the years?

GH: I can usually tell when the story is overtaking the characters if characters start making decisions that seem truly for the sake of making a specific thing happen, as opposed to choices being the natural consequence of where they are emotionally. People make all sorts of terrible, contradictory decisions all the time, but there is always some emotional, internal consistency. Even if the reasoning is revealed later, a choice needs to make sense for the character.

I find the room starts to get really stuck in a break when we’re focused solely on plot needs that contradict character. Nothing quite fits and connective tissue starts to get sloppy. That’s usually the moment when I’d ask, “Where is the character’s head at?” That question, specifically, is one that I learned from Vince Gilligan. That said, I do think I have always had a very good instinct for character, so I feel it’s probably a combo of my gut and years of working with wonderful writers who ask the right questions.

“People make all sorts of terrible, contradictory decisions all the time, but there is always some emotional, internal consistency. Even if the reasoning is revealed later, a choice needs to make sense for the character.”

CH: Okay, stepping back. I’m curious about the raw material you started with as a storyteller. First, when did you first realize that might be what you were and, second, what kind of storyteller did you assume you’d become?

GH: I think I started focusing on writing stories in high school, but I’d always had a very active imagination and spent a lot of time as a kid building elaborate worlds in my head when I played games. I was a huge reader, so I assumed I’d be an author, but I never said that’s what I wanted to be when I grew up. Usually whatever I wanted to be was based on a movie I’d seen.

CH: Can you give me an example? I had this same problem myself, if we want to call it a problem.

GH: I saw STAR TREK IV and wanted to be a cetacean biologist. REGARDING HENRY made me want to be a physical therapist. Clearly, movies were hugely influential for me.

CH: What began to point you toward film or television rather than writing prose fiction?

GH: I’d always loved TV and movies, but in high school, I got very into independent film. It was the nineties indie film renaissance, and there was a single art house theatre in the next town over that I went to every single weekend with my best friend. I’d say that’s when I started seriously thinking about wanting to make movies. I assumed I’d focus on directing, even though, as I said, I’d always written. I briefly considered acting, but I’m way too self-conscious for it. In college, I really started considering that I wanted to be a screenwriter. The idea of writing for TV, as opposed to film, came later, after I started working in the industry.

CH: Can you remember the first screenplay you wrote? I presume it was a feature. I’d love to hear about it, both your memories of it and how you think about the attempt and your writing in retrospect given where you are today.

GH: In college, I took the single screenwriting class my school offered and wrote a half-hour drama pilot, very likely about myself and my friends. I remember nothing about the story, but I remember really enjoying writing it. It felt natural, particularly when writing dialogue. That was kind of the spark, like I’d found my medium.

What I would consider my first real screenplay was a feature. It was a modern retelling of THE WIZARD OF OZ, focused on two sisters running away from their abusive aunt after she gets custody of them when their mother dies. They end up unhoused in Los Angeles and meet three other lost souls who were my stand-ins for the Lion, Scarecrow, and Tinman. The Wizard was a Dr. Phil-type, and they try to get on his show so he can help them find a safe home. I haven’t thought about it in ages, but looking back, the idea still sounds fun, actually.

CH: It absolutely sounds fun. It sounds kind of amazing, honestly.

GH: Thank you! It may be time to revisit it. When I was writing the script, I remember taking way too long with it. I got very hung up on perfecting it, so it took me a while to get feedback. I was so nervous about it, and that hasn’t really changed. I still feel a bit ill giving people my work to read, anticipating the worst. I’m more confident in my writing ability now, though. It’s just the process hits all those perfectionistic triggers.

“I took the note, but executed it poorly. I’ve learned how to better analyze and integrate notes – how to answer the note in the way that works best for the story I’m trying to tell.”

GH (cont’d): From my memory, it was very character-focused, which I’m still very much about. I know I was trying to be very grounded in my dialogue and storytelling, though a friend who read it requested more magical elements. That threw me, and I took the note, but executed it poorly. I’ve learned how to better analyze and integrate notes – how to answer the note in the way that works best for the story I’m trying to tell. But that’s mainly about being confident in my voice and point of view.

I’m still very interested in finding new ways into classic stories and fairy tales, but I think I’m more sophisticated in how I approach those ideas. Or, at least I hope I am.

CH: I know you grew up in a military family, but does that mean one or both parents?

GH: My parents were both in the service when they met, but they both got out after I was born. My father later re-joined the Air Force, so it was just my dad from when I was about six through fifteen or so.

CH: My father took a similar route, except he started out in the army in Vietnam and re-upped as National Guard a few years later. Did you make sense to your parents as a child? What I mean is, did they understand this creative spark of yours?

GH: A lot of people I’ve talked to assume that military parents are conservative, both politically and philosophically. My parents are neither and both are creative people themselves – writing, art, music, crafting. I think my creative nature seemed natural to them. They’ve always been encouraging of my writing — my dad, unprompted, got me Final Draft when I graduated college — even when they’ve been very worried about the financial viability of my chosen career path.

CH: You started out as a writers’ assistant, which eventually led to your first job as a staff writer – which I believe was on “BREAKING BAD”, correct? How did you land in that room?

GH: I worked for Vince Gilligan as his assistant on the later seasons of the original “THE X-FILES” run when I was first starting out in Los Angeles. After it ended, we stayed in touch. In the many years between “THE X-FILES” and “BREAKING BAD”, I bounced between shows as an assistant before landing on the first season of “MAD MEN”, working as Matthew Weiner’s assistant.

Season 1 was wrapping up, and one of the AMC executives offhandedly mentioned they were doing a show with my old boss, Vince. I immediately reached out to him, not knowing anything about the show, and asked him to please hire me as an assistant. Vince is one of the most talented writers I’ve ever worked with, so I knew it was going to be great no matter what.

“Season 1 was wrapping up, and one of the AMC executives offhandedly mentioned they were doing a show with my old boss, Vince [Gilligan]. I immediately reached out to him, not knowing anything about the show”

GH (cont’d): He hired me right away as his assistant, but I ended up taking notes in the room because, at the time, the show did not have a traditional Writers’ Assistant. But as Vince’s assistant, I went to set with him in Albuquerque once production started, so I got to be in the thick of filming Season 1, which was awesome. That season was cut short by the 07-08 WGA Strike, and I was let go.

Once the strike ended, I met with Vince about coming back for Season 2 and pitched myself as the full-time Writers’ Assistant and told him I wanted to write on the show. I asked him what I needed to do to show I was ready. He asked to read samples and suggested I write any bonus content I could for the show. I ended up writing some webisodes and “Hank’s Blog” for the website, which he always found delightful.

GH (cont’d): When Season 3 was picked up, I asked him to staff me. He told me he would give me a freelance episode, and it if went well, he would promote me to Staff Writer. I wrote my first episode that season, and it was nominated for a WGA Award. He staffed me full-time in Season 4.

CH: For readers, I want to point out that episode was “I See You”, which was a hell of a way to make your debut in this business as a writer, Gennifer. It’s a phenomenal episode of TV.

GH: Thank you. I feel exceptionally lucky.

CH: So, tell me about your experience on “BREAKING BAD”, from your relatively rookie perspective. How quickly did it become obvious to you that something special was happening and you had somehow wound up part of it?

“I knew it was going to be special before I really knew anything about it. I can’t quite explain how good a Vince Gilligan script is … but once you read one, you know he’s a singularly talented writer.”

GH: I knew it was going to be special before I really knew anything about it. I can’t quite explain how good a Vince Gilligan script is — and I’d read many of his first drafts while working on “THE X-FILES” — but once you read one, you know he’s a singularly talented writer. I was excited for him to be making his own show with a decent amount of creative freedom. Once I read the script and saw the pilot and the incredible work on the screen from the cast and crew, it just confirmed it was going to be a great show.

But I didn’t realize it was going to be a phenomenon until right after Season 3 when it started streaming on Netflix. We went from being that unknown show on the channel that aired “MAD MEN” to “You work on BREAKING BAD?!” very quickly.

CH: I’m curious what “BREAKING BAD” taught you about yourself as a storyteller or person. I’m endlessly interested in our mistakes as writers, our erroneous assumptions about how story works or TV works or even our overconfidence about how much we know, and so on. In those mistakes, in how we grow because of them, there’s so much to learn from.

GH: When I started on “BREAKING BAD”, I’d been an assistant for nearly ten years. I’d missed some big opportunities because of cancellations or staffing changes or timing, and I was experiencing pretty serious burnout.

CH: After ten years, I can imagine.

GH: In retrospect – all those disappointing missed opportunities were at jobs where I met people and formed connections, and they all very weirdly and serendipitously led me to “BREAKING BAD”. I’m very grateful, even though those previous years were often very painful.

“All those disappointing missed opportunities were at jobs where I met people and formed connections, and they all very weirdly and serendipitously led me to BREAKING BAD.”

CH: As they say, the journey is the destination, but, Christ, the journey breaks so many of us or comes close to doing so. Sorry, you were telling me what “BREAKING BAD” taught you.

GH: I’d gotten very complacent as both an assistant and about my own writing. I was sabotaging myself in ways I didn’t realize at the time. Being on “BREAKING BAD”, a creatively inspiring show run by a kind and talented boss, was a good wake-up call for me to focus on really pushing to get over that first mountain to staff writer. “Making it” is about being ready for the luck to hit. I’d found the luck, but I’d done a lousy job being ready for it.

Once I was staffed, having been in rooms for a decade-plus already made that first day as the “rookie” staff writer way less intimidating. I knew how a room worked. I understood hierarchy and how to critique a pitch in a way that builds on the break instead of tearing it down.

GH (cont’d): The big thing I had to learn was confidence in my position as a writer. I was still very much in an assistant headspace. I had to push back on ideas in the room if I felt I had a better pitch. I had to assert myself on set creatively and be collaborative as opposed to just validating. That was challenging. I realized how good I’d gotten at managing up, but I had lost a lot of my own voice. So, I had to find it while also, you know, writing in someone else’s voice.

CH: Not always easy in the best of times.

“It also showed me that I needed to be braver in my storytelling, to lean into the ideas and plot or character moves that scared me.”

GH: Luckily, that voice was an amazing one, and working in that room made me much more rigorous in my storytelling than I’d ever been. I was always instinctually following my characters but “BREAKING BAD’ gave me the right questions to ask – the tangible aspects of building a character’s journey. It also showed me that I needed to be braver in my storytelling, to lean into the ideas and plot or character moves that scared me. When I wanted to play it safe or I’d get too internal, that room constantly reminded me to push past that.

CH: I’m curious how you would describe yourself as you arrived for Day 1 of the “BETTER CALL SAUL” writers’ room, then. Obviously, there were a lot of familiar players there. For example, what challenges did “SAUL” pose for you, as a writer, or as a person, that forced you to grow in new directions?

“I didn’t have any idea who Jimmy McGill was or why he was important. I think all of us likely struggled a bit with that.”

GH: Coming into “SAUL” was interesting because, with “BREAKING BAD”, the show was fully formed by the time I was writing for it. With “BETTER CALL SAUL”, even though we knew the character already — or thought we did — the show was still pretty nebulous when we started writing Season 1. [Co-creators] Vince [Gilligan] and Peter [Gould] had their pitch, but we really discovered the show itself together.

I learned to stop making assumptions about the limits of a character. One of the biggest challenges for me was wrapping my head around focusing on “Saul” as a full character and not just the supporting comic relief. I’d seen how great Bob Odenkirk was dramatically in the later seasons of “BREAKING BAD”, so I knew he could thrive in a deeply complex story, but I didn’t have any idea who Jimmy McGill was or why he was important. I think all of us likely struggled a bit with that.

GH (cont’d): I remember at a certain point, we all shifted from calling him Saul to calling him Jimmy, and that’s when I knew we were getting to the heart of the show and defining it as something special in its own right. Suddenly, I loved Jimmy and was deeply mournful about him becoming Saul. Luckily, we’d always planned it as a redemption story.

I also had a very strong connection to Kim’s character, more so than I’d had in the past, and I had to learn to balance my personal vision of her with the showrunners’ visions. Picking which fights were in service of making the show better and which were about me being “right” was a learning process.

“I had to learn to balance my personal vision of her with the showrunners’ visions. Picking which fights were in service of making the show better and which were about me being ‘right’ was a learning process.”

CH: You said the “BREAKING BAD” writers’ room taught you to lean into the ideas, the plot and the characters that scared you. Carrying that over to “BETTER CALL SAUL”, can you recall a moment on “BETTER CALL SAUL” that you had to do exactly that and what the results were?

GH: As a whole, I think the scariest part of telling that story was how different the stakes were than in “BREAKING BAD”. With the previous show, it was almost always life or death stakes. With “SAUL”, especially early on, the stakes are much more personal. They’re about Jimmy’s soul. They’re about Kim’s integrity. They’re about this deeply felt, loving relationship that is destroying the better parts of each of them…but that also leads them back to those better parts. Even though the existential stakes grew with each season of the show, I think just letting the stakes of Jimmy’s story often be personal and small and “mundane” in so many moments was nerve-wracking.

A more specific example would be the development of Chuck’s character. He was initially written to be a victim, but as the story progressed and we saw, particularly, how Michael McKean chose to so beautifully portray him, we realized that he was actually a villain. Leaning into that was a point of no return. It was very subtle and delicate, particularly with how his story ends.

CH: All good things must come to an end, including this conversation. I’d like to conclude by reflecting upon your journey, because you’ve very much worked your way up the ladder as we’ve discussed at length. Not a lot of aspiring writers, even those who are in the process of breaking in themselves, really understand the value of that. We’re a McDonald’s culture in so many ways. We want everything, including success, fast. But I find a lot of quick success doesn’t necessarily produce enduring careers. More often than not, it doesn’t even produce truly great work.

GH: I would not be the writer I am now, nor would I have had the career I have if I’d broken in earlier. Just having the benefit of years of practicing my writing has improved it tremendously. Life experience has focused me. Professionally, spending so much time around the process as an assistant was integral to helping my transition to being a staff writer. I would have made so many more mistakes without it. And if I’d sold a show before staffing, I have no doubt I would have crashed and burned. Or, even if I scraped by, I would have gone through very similar, or worse, pain to what I did experience – just on the back end.

“I think that TV writing is an apprenticeship craft, which inherently means time spent gradually ascending a ladder. My writing benefited in immeasurable ways because I learned from great writers.”

GH (cont’d): I’ve seen it happen to other writers, particularly around selling a show before they’ve ever staffed, and it’s always heartbreaking. People are selling shows more and more without having staffed, and even when the show is great, I still feel there’s a loss there.

I think that TV writing is an apprenticeship craft, which inherently means time spent gradually ascending a ladder. My writing benefited in immeasurable ways because I learned from great writers. Taking one’s time to learn and grow and be humbled is valuable, and it really hurts writers – and the business as a whole – that so much emphasis is put on being the prodigy.

That said, I don’t subscribe to the idea that suffering is necessary to reach one’s creative potential. It shouldn’t be as painful as it often is. No one should be physically and emotionally destroyed trying to make it in this career. It’s absurd. Obviously, our experiences shape us and play a huge role in whether we succeed or fail but mythologizing the struggle as integral to the result often seems like a way to normalize abusive or exploitative behavior.

I feel like I’ve been very introspective lately overall. It’s easy to wonder “what if?” But when I look back on my journey, while it was long and difficult, I can’t really see it any other way. I mean, I would happily lift out any of the parts working with terrible, abusive people, obviously. But as a whole, I’m so grateful I had the time and space to find my creative voice and actually be ready to successfully use it.

Find Gennifer Hutchison on Not-Twitter and Bluesky.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: