Q&A: Filmmaker Tony Ayres on the Secret of His Success

The screenwriter, director, and producer looks back on his career and how he became one of the leading voices in Australian TV by living up to his Chinese sign

My first stretch living in Australia as an adult was in the early part of this century, and while here — ostensibly to study, but mostly to explore my mother’s country — I consumed as much homegrown cinema as I could. This is how I first encountered Tony Ayres’s name as the director of Walking on Water (2002), a small drama film I’m pretty sure I caught at a local festival - though my memory for such things is dicey these days. Fifteen years later, in December 2019, I sat down with him for tea at Dean Street Townhouse in London’s Soho; we’d been “set up” by our mutual U.K. agent, Cathy King, who thought we should know each other. I found him warm, generous, and thoughtful; I liked him immediately.

In the nearly two decades in between these two experiences, Tony had evolved into one of Australia’s most successful TV creators, showrunners, and producers. Selfishly, I hoped we’d hit it off as we sipped our tea because, while I was living and working in the U.K. at the time, I was very keen to break into the Aussie film/TV industry, too. I had secret aspirations of eventually moving there.

Our professional meeting was a different kind of successful, though. Rather than walking away from it with a potential collaboration based on one of the ideas I’d been developing, I’d instead made a friend. Or at least a relationship with someone whom I could reach out to for a very specific kind of advice, which I eventually needed a lot of when, in 2021, my family decided to permanently settle in Australia. Tony has since continued to be a reliable source of counsel when called upon, a rare gift in any country and industry.

I’m truly thrilled my mate agree to join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations.

Now, if you live outside of Australia, you might not know Tony’s name as well as I did, but I suspect you’ve seen his work cross your screen on more than one occasion as you patrol streaming platforms’ offerings. As the country’s TV has become more and more internationally popular, his work has spread around the globe including the series he’s created or co-created and showran like “Nowhere Boys” (2013), “Glitch” (2015), “Stateless” (2020), “Fires” (2021), and “Clickbait” (2021). Tony next showruns “The Survivors”, an adaptation of the Jane Harper novel, which premieres on Netflix next year.

He’s also directed numerous episodes of TV, as well as two other feature films — Cut Snake in 2014, but, more germane to the conversation we’ll be having today, The Home Song Stories seven years earlier. The Home Song Stories (2007) is a film not widely available to international audiences, but please, take my word for it, it’s an exquisite, heartbreaking, beautifully inspiring piece of autofictional storytelling. You’ll find a link to the trailer within the article. There’s a lot to learn from Tony’s relationship with this film and its story and his reflections on it seventeen years later.

What you’re about to read is a sprawling conversation with one of the most dominant voices in the Australian TV market — though, maybe I should explain what that means. Two years ago, I worked with producers who asked him for advice about a project I had with them; they began a subsequent conversation with me by saying things like, “But Tony said…” This was repeated several times, in fact — “But Tony said…” Because if Tony says it, it must be right, or at least when it comes to his local market. That said, his wisdom can be applied anywhere people dream of becoming screenwriters, struggle to bring something authentic to our screens, and wrestle with success and compromises and obligations that can come with it. There is so much that screenwriters — and directors — at all levels of their creative journeys will learn from this conversation. Now, let’s dive in…

COLE HADDON: Tony, I’m very excited to have this conversation with you for many reasons. To kick things off, I wanted to ask about identity and your relationship to the moving image. I can explain that better, if you give me a moment. You’re an immigrant from Macau, an Australian of color, and queer. You grew up during the last decade of the White Australia policy, were orphaned as a young teenager, and found a footing in a film/TV industry at a time when so many of the labels that could be applied to you were likely seen as negatives to many. It’s an extraordinary backstory – at times, I’ve thought you sound more like a character in a piece of literary fiction rather than someone I know – and so, to bring it back to the moving image, I’d like to ask if there’s a film or TV series that has made you feel seen in your life? That seemed to be speaking directly to you - that is, if such a story even exists.

TONY AYRES: I think the thing that we always have to be careful of is assuming that that audience members cannot imagine something other than what they literally look like. I think that certainly if you come from a non-white racial background, you learn how to do that very quickly if you're in a Western country. Maybe if you're not in a Western country, like if I was raised in China, it would be more unfamiliar to me, but the first things I saw were people on screen who were not me – and that did not stop me from being affected and moved by those stories.

CH: I ask these first questions to provoke interesting answers, and sometimes I get lucky and someone blows up conventional or popular or whatever-you-want-to-call-it arguments. Thank you for not disappointing. Please, continue.

TA: There were certain films that kind of triggered a different kind of recognition for me, a more familiar kind of recognition. Like My Beautiful Launderette did that when I saw it for the first time because it was a love story between a brown person and a white person. And at that stage in my life, I'd never seen that before. I was in a mixed-race relationship, so that triggered a different kind of familiarity. But I watched Brideshead Revisited and I was deeply moved by that. I was profoundly affected by movies like Ken Russell's Women in Love, The Graduate – a lot of Mike Nichols's work. Robert Altman's work, too. They were probably the stories that most deeply affected me.

I also feel like I always related to narratives about outsiders, and I think that in terms of conscious identity, I always felt like I was an outsider. Weirdly, even though I'm one of the most inside people I know, I still feel like an outsider. It's like how your class of origin can so deeply impact upon your personality. It's like rich people who still pack their lunches or things like that. To this day, my emotional wiring connects me to outsider stories.

CH: Tell me more about that.

TA: Those were the stories that deeply influenced me when I was younger. But I was lucky because I got to have an education. I went to university, and I moved from my underclass world into a very middle-class world. I met my partner Michael when I was seventeen years old. I transitioned from one class to another, and that sort of transition gave me the opportunity to forge a life for myself, which would've been completely unthinkable even from the age of sixteen down. The kind of life I live now was absolutely impossible. My aspiration back then was to be a bank teller.

CH: Really?

TA: That seemed to be the highest aspiration for what I could do with my life. And because it involved security and money – and they were things that I'd never had. Even becoming an artist or becoming a dramatist or a storyteller, they were completely outside the limits of my imagination until I got to university and started mixing with all these other people. Then I ended up going to art school on a whim — really, it was nothing more than that.

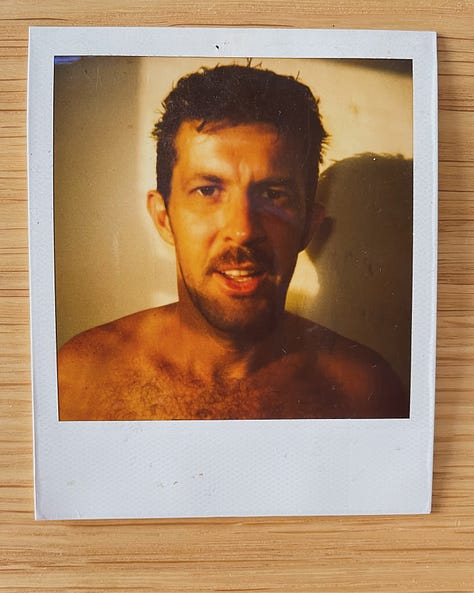

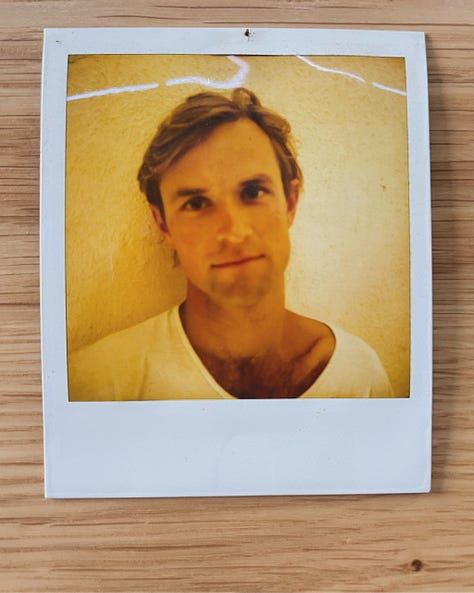

CH: Now that you’ve at least alluded to how you found your way into the world of art, this might be a good place to pivot to what inspired this conversation in the first place. As I mentioned when I first emailed, I’d been meaning to reach out to you for a while about having one of these chats. But I found myself especially motivated to do so by a series of Facebook posts you shared over several months this year after you found a bunch of old Polaroids from a six-year stretch you lived in Bondi from 1989 to 1995. Each Polaroid was a portrait of someone who passed through your house.

CH (cont’d): I wish there were a word in English for being nostalgic for something you never experienced yourself, but this series of pics from you made me feel that. I lived in Bondi almost a decade later and, for a blip in time, contemplated staying. I think maybe I saw the artist life I missed out on in all the faces you shared. Anyway, the point of all this preamble is, the Polaroids you shared felt reflective. As they overlap with the period in which you began to establish yourself in the Australian arts world, I wonder if you could tell me how you remember this period in your life. How do you remember yourself at this point in your story, and what were you trying to accomplish in your life?

TA: Okay, so when I moved house recently, I found this box of Polaroids from when [my partner] Michael and I lived in Bondi in the mid-nineties. I took a photograph of everyone who came into our apartment to visit, and I put it up on a pinup board, and it was just like a record of our social time in Sydney. We'd moved up from Melbourne. I had gone up to go to AFTRS, the Australian Film Television and Radio School, to do a postgraduate diploma in screenwriting. Michael followed me soon after to work at the Arts Law Centre; he was a lawyer at the time. And I guess those days when I came up to Sydney, they were a pivotal moment for me because I wasn't sure whether I would stay in the screen industry or not.

TA (cont’d): I had gone to VCA [Victorian College of Arts] a few years earlier, but before that I had done a degree in Visual Arts and done an undergraduate degree majoring in Philosophy and Literature. And so, I could have gone in several directions, including academia. It was only when I went to AFTRS and met a woman called Barbara Masel, who was teaching there at the time, that I finally realized that what I wanted to do was screenwriting. I'd been kicking the tires up until then, I think, and I was certainly unsure of whether I had the ability to do it. Weirdly, the most profound thing that happened to me was Barbara said, “Oh, you can write.” Honestly, up until then, I really didn't know whether I could or not. It was something that I really wanted to do. I'd written short stories since I was a teenager all through university, but I'd never had anything published. I barely showed anyone.

CH: So, I assume it was all very personal for you?

TA: Yeah, it was very personal for me. Writing was a way of processing thoughts and feelings that I was having, which I didn't understand or which troubled me. It was a sort of form of self-therapy me. So, to think that I could do it full-time as a living was both a dream and a nightmare – wanting it so much that it was scary to even try. I guess that's a long way of saying that that point in my life was really when I just went all in for it and just gave it a red hot go.

CH: What did that mean for you?

TA: I mean, I was hustling. I was writing press releases for an SBS educational video show called “English at Work”. I was working part-time as an usher at a cinema. I was just doing everything that I could possibly do. And I did some documentaries. I made some short films for SBS with Annette Shun Wah and Debbie Lee in for a show they had called “Eat Carpet”, which was an extraordinary arty late-night time slot, which barely anyone watched, but they commissioned these wacky works – and I got to make three things for them, which was brilliant. I was kind of finding myself and because Michael and I were newcomers to Sydney. We were sort of creating a social family for ourselves, as well. It was an idyllic time, but it was also a tough time because you are laying the foundations for a career you're trying to work out.

CH: How did you fit in with your peers at this period in your life?

TA: I think I was different from a lot of my peers at film school and the young writers around me insofar as I knew what I wanted to say. Back in those days, a lot of the work I was most interested in was identity-based work around my own experiences. There wasn't much competition within the same field, say. A lot of the white writers who were my peers were always being beaten by someone else who was also telling their story, or they were trying to work out what story they wanted to tell and what was their unique perspective on it. That wasn't so difficult for me because my perspective was unusual. I came from being gay and Chinese and from an immigrant background, and so my kinds of stories were exceptional back then. I never had to worry about anyone else doing my story.

CH: What did you have to worry about, then?

TA: What I had to do to convince people that my story was worth telling. And I think that back then, it was struggle.

CH: What was that like, to love something so much that maybe didn’t love you as much back? Did that impact your creativity, how you worked, your mental health, any of these things? Even how hard you worked?