Q&A: Ed Laroche Discusses His New Image Graphic Novel ALMIGHTY

The artist breaks down his post-apocalyptic tale, storytelling process, and the intersection of comic books, cinema, and music in his work

(This is a bonus feature available to both paid and free subscribers.)

I’ve been a fan of Ed Laroche for as long as I’ve known Ed Laroche, which is more than a decade now. The storyboard artist-by-day and graphic novelist-by-night and I struck up a friendship over long movie marathons in my living room — this was back when I lived in Los Angeles — drawn to each other as much by our love of cinema as artistic philosophies that overlapped by half. The half that didn’t has provided us no end of entertainment through lengthy debates about the nature of art in all its forms as well as the role of art criticism, none of which ever seem to get resolved.

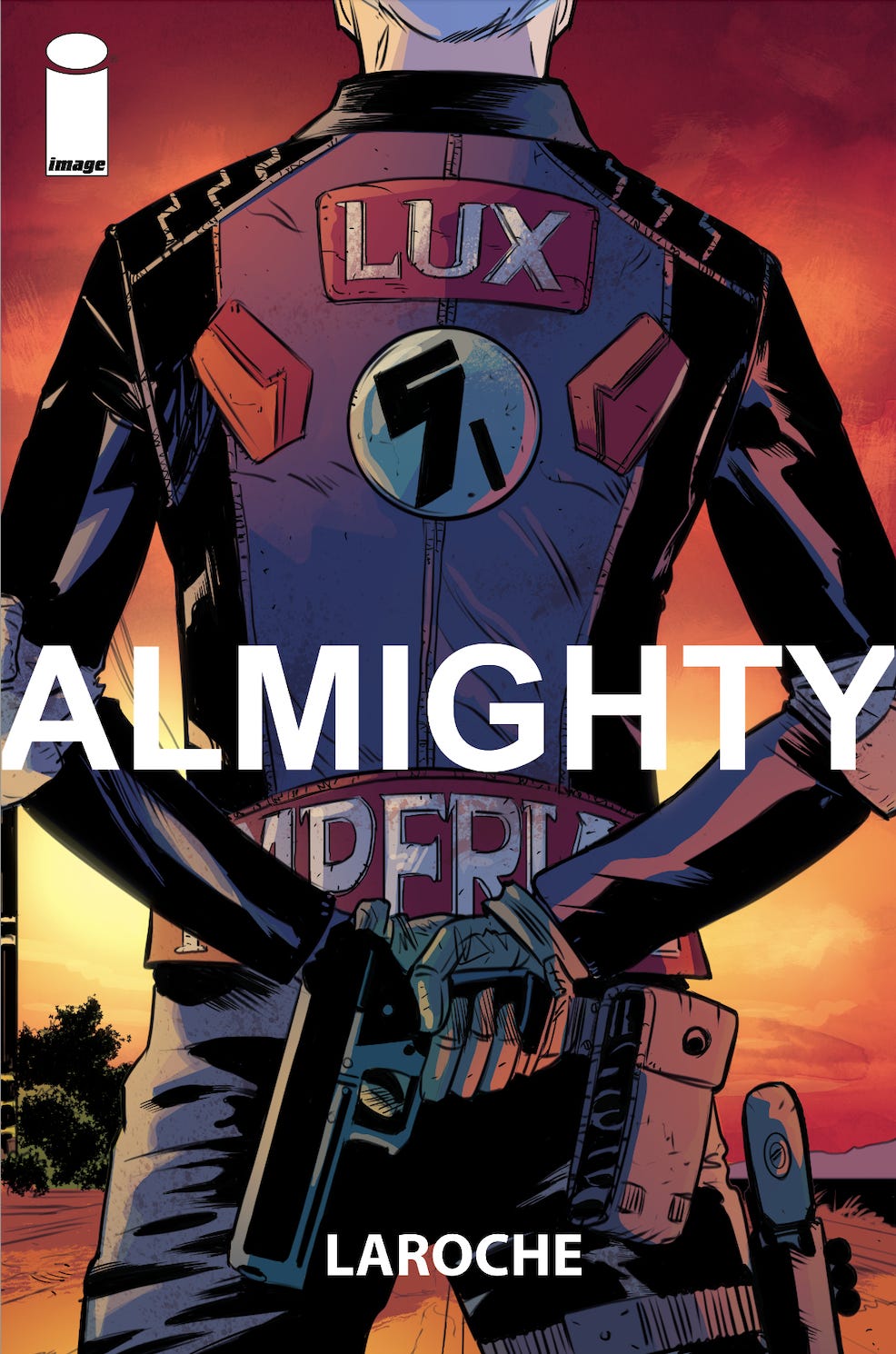

On September 13th, Laroche’s latest comic book series will be collected and released in a new trade paperback from Image Comics. ALMIGHTY is a harrowing tale of an abducted girl and the professional killer — a killer with unique abilities — who is hired to find her. It’s set against a post-apocalyptic backdrop populated by corrupt law enforcement, violent biker gangs, and environmental collapse. Like a lot of the work in this space, much of what I just described sounds familiar enough to many of us, but Laroche distinguishes his story through a cinematic style at times elegiac — suggesting a kind of horror-poetry — and, at others, action-packed and explosively violent. I’m excited to be able to talk with him about ALMIGHTY and our mutual passion for the arts.

COLE HADDON: So, I’ve read ALMIGHTY, and it’s excellent stuff, my friend. I mean that. The world-building is confident and, I think, incredibly patient in how it’s doled out. There’s a real sense of starting small, in an extreme close-up, and then slowly pulling out and out and out until you get the big picture. I really appreciated that.

ED LAROCHE: Yes, thank you. You’re highlighting something I really love about these types of genre stories, which is scale and the best way to depict it is to either start small and go big, or start big and go small depending on what kind of emotional beat you want to end on.

CH: I’ve already shared my own description of ALMIGHTY, but why don’t you tell me what it’s about in your own words?

EL: ALMIGHTY is a dystopian, science fiction/horror story set in the near-future where a young woman has been abducted by a motorcycle gang, and an ex-military contractor is hired to find her and bring her home. It’s heavily inspired by post-apocalyptic films and books like Yul Brynner’s THE ULTIMATE WARRIOR, James Axler’s DEATHLANDS series, and Tetsuo Hara and Buronson’s FIST OF THE NORTH STAR. Have you seen THE ULTIMATE WARRIOR?

CH: I know I have, but it’s been at least thirty years, probably closer to forty. Should I revisit?

EL: I think you’d love it, man. Max Von Sydow is great in it, as well.

CH: These are the times I miss living in Los Angeles, when I could just have you and the rest of our mutual friends over for an all-day marathon of seventies-era apocalyptic cinema. Then again, you don’t live there anymore either. But those were good days.

EL: Yeah, those were great times, and a very interesting group of movie lovers you were able to gather together. I miss it. I guess that’s L.A. for you, weirdly impermanent as the world shifts out around you. I’ve been back a few times since I got on the road. Same sites are there, same hiking trails, but the people we knew have moved on. The scene that was L.A. at the time does not exist anymore. I guess that’s fine, it makes those moments even more special.

CH: How do you feel ALMIGHTY contrasts with THE WARNING, which was your last book for Image? A ten-issue series I very much enjoyed.

EL: ALMIGHTY is different in the way that I’m telling the story, in that it’s not as complicated. It’s more straight forward with minimal expositional flashbacks. One of the things I learned from THE WARNING is that some folks have a tough time with flashbacks and jumps in time.

Funny thing is, I’m building an animatic of THE WARNING for a pitch to a screenwriter friend of mine who loved the book as it was coming out but took a break before finishing it, and, when he came back to it, he felt lost in the story. So, what I’ve done is I’ve broken it apart and assembled it in order. I’ve watched it several times as I tweak it, and so far it’s been a fascinating experiment.

CH: I’d be interested in seeing the end result of that experiment.

EL: I’ll send it to you when I’m done.

CH: Following up on what you just said about how some people reacted to THE WARNING, I’m curious to what degree do you take your readers into consideration as you work? How would you describe your relationship to them as you dream up and ultimately realize your graphic novels?

“What the audience needs is always part of the process, but how they get it is up to me, and that’s where the artistry of it all comes into play.”

EL: Great Question. What the audience needs is always part of the process, but how they get it is up to me, and that’s where the artistry of it all comes into play. At the same time, I am sensitive to the zeitgeist of it all. For instance, during the lockdown I was working on another book that, at the end of the day, I just didn’t think the audience would be there for, so I put it down and started working on something less ambiguous and more straight forward. Something simple and just straight up meat and potatoes.

CH: Let’s talk about your journey for a moment. We’ve had so many conversations about the arts over the years, but I don’t think I’ve ever asked you: when did you know you wanted to become an artist yourself? Was it a moment of clarity, or a journey getting to that understanding of yourself?

EL: Well, there have been different stages of what being an artist meant to me on the road to becoming one. At first it was a competition to be better than friends and family who were artists in their own right, and later it became a way to cope with the solitude of being an only child. It wasn’t until much later that I was able to see it as a lifestyle and a philosophy that would make it possible for me to identify myself as an artist.

CH: Where did you grow up?

EL: I was in born in Los Angeles, and grew up on the north side of Atwater closer to the Glendale border right next to the train tracks. It was known as Toonerville back then, and the south side of Atwater was called Frogtown. I went to Glenfeliz Elementary and then to Irving Junior High for a year before being sent off to a Christian military school in Long Beach called Southern California Military Academy.

CH: What kind of an impact did military school make on you?

EL: It was one of those things I hated as it happened, but in retrospect I came to appreciate parts of the experience. They had a motto at that school that’s stood the test of time: “Character before career”. I didn’t know what that meant the first time I read it, but it stuck with me, and so far I haven’t found it to be untrue.

CH: And after military school?

EL: After that, I went to John Marshall High School.

CH: Oh wow. That name makes me immediately start hearing GREASE songs.

EL: Yes, it’s famous for all the movies, TV shows, and music videos that have been shot there.

“I never thought about making a living as an artist because that’s not the type of thing a child of immigrants would be encouraged to pursue with the gift of being born American.”

CH: So, where did the arts fit into all this?

EL: I started drawing at a very young age —

CH: How young?

EL: Around eight — and I just kept at it, it was something I enjoyed doing, especially after I started to see improvements in my work. I never thought about making a living as an artist because that’s not the type of thing a child of immigrants would be encouraged to pursue with the gift of being born American.

CH: Can you tell readers where your family came from?

EL: My parents and the extended family fled the coup in Haiti, and for the most part settled on the East Coast. My mother, the youngest of twelve, had different ideas, and moved to Los Angeles.

CH: What I’ve always loved about your graphic novel work is how important tone is to both your art and the stories that go along with that art. Maybe atmosphere is a better word. Or vibe. I like vibe. You do it better than most artists I follow, and pacing is huge part of that because you seem to be operating in a comic book world wholly unique to you and your voice. That voice is as deeply informed by cinema as comic books, especially cinematography and editing in both art films and action films. When I read you, I often find myself thinking I’m reading a graphic novel from director Terrence Malick, frames as carefully constructed as his, languidly edited together to create a poetic visual tapestry pregnant with existential meaning — then, blam, the story explodes into a Michael Bay action sequence. Talk to me about how you developed this hybrid style.

EL: That’s an interesting question. I would have to say it came on organically, but at the same time there may be a part of me that is just inclined to perceive and transmit what you are talking about.

I know music has been a very important part of it, the forming of my approach, which at its core is musical and lyrical, and there have been many friends that have turned me on to different albums and musicians that have inspired me. For instance, my friend Marcus Ramirez — who was an amazing artist who got a scholarship to Otis/Parsons — introduced me to the music of Peter Gabriel, Kate Bush, and early U2. To him, music was a deeper thing, a spiritual expression. He also impressed upon me the importance of keeping a sketch book and how something like that could be used to explore ideas and jot down feelings, like a journal.

Sometimes we would park on a random street at night, huffing nitrous oxide from cans of whipped cream, listening to Peter Gabriel’s PASSION, letting the sound washed over us, which, in turn, would inspire many visions of fantastical stories and feelings.

Perhaps, more importantly, Marcus turned me onto Ron Fricke and his movie CHRONOS. The first time experiencing that was a seminal moment in the creation of my approach. We watched that more than a few times on LSD at one of the first IMAX screens in the world in the California Science Center.

“Music is one of the things I need to be able to control the conditions in which creation is possible.”

CH: You just made several references to music. I’ve always known it plays a big part in your creative process, but could you explain how that works for you? How does music shape your work in graphic novels?

EL: I listen to music everywhere I go whether I’m walking down the street, standing in line, or waiting at an airport — I’m always listening to my own personal soundtrack. Music is one of the things I need to be able to control the conditions in which creation is possible. In other words, it puts me in a creative mood. I listen to a lot of ambient music, so it’s a perfect fit.

CH: I’ve often struggled to explain my own use of music, the role it plays in my own process. I’m going to steal that next time someone asks me about it - “it allows me to control the conditions in which creation is possible.” Because that’s exactly it, I think.

EL: Absolutely. I think music is a great tool to bring on that meditative state that can lead to creation. I think for me, if I can just tap into music, something that inspires me, I can draw or contemplate about story anywhere I go.

CH: You’ve also worked extensively as a storyboard artist on a lot of big films. There’s a direct correlation between storyboarding and comic book panels, of course. What kind of an impact has this work had on your narrative and visual style?

EL: Working within the aspect ratio of a storyboard frame helps me focus on the visual narrative of the story I’m telling. It’s probably the one thing that sets my work apart from most comic books. Comics are about page layout and leading the eye, and I tend to do that with shot choices, solid mise en scene, and longer scenes that play out.

CH: Those longer scenes are certainly part of what I love so much about your graphic novels — and you’ve taken them to the next level in ALMIGHTY. Instead of cramming a scene into a page, you let it breathe and build like a film. One challenge I’ve sometimes found with illustrators is that, as brilliant as they are, I see story in terms of cinema. This means a kind of visual movement that is very different on screens than on the page, so I’m always pushing for a more “cinematic experience” — similar to what you were just describing. Unfortunately, I also write incredibly dense comic books, which really handicaps the ability to achieve that when you’re operating in, say, a four-issue series space and you’re telling a really big story. Your work, by contrast, puts a heavy emphasis on visual storytelling, sometimes more “silent film” than a traditionally scripted comic book story. Is that intentional on your part?

EL: Yes, I write it visually. My work in TV, animation, and movies gives me a pretty good feel of how long I want to stay in a sequence, and also how I want to cover it. That being said, sometimes I have to write out a scene before drawing it because there’s a bit of exposition and important emotional beats I have to follow, and I want to do it in such a way that it’s interesting for me and the reader.

When you work on your books or scripts, do you lay out scenes on flash cards and play with the order of when things happen in the story? Kind of a more structured Burroughs’s cut-up method of seeing what the story can do?

CH: With screenwriting, definitely. Flash cards and Word sort of work interchangeably for me, depending how big the story is and how I need to “see it”. I tend to work with overlapping outlines, one plot and one the emotional narrative. Then I mix things up as I work to find the right order. As for my first novel [PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD], that was completely different. It’s a mosaic story with many different characters across many time periods. I just wrote, kind of unleashed, all intuition. Later, it was very easy to rearrange them, to put the musical notes so to say, in the right order after I had written all the chapters and found out how they spoke to each other.

But let’s get back to you. Most comic book illustrators don’t write their own books. How naturally does that come to you and which part of the process do you hate most?

EL: I can’t really say I hate any part of the process. It’s just an endless fascination for me. Although I will say that I really love tweaking things after everything is pretty much done. Addressing things that bother me about the work is very satisfying.

CH: I don’t think I’ve ever read anything that you illustrated, but didn’t write. This has always given me the impression you’ve chosen to pursue an auteur take on comic books, bringing your own visions to life with as much creative control as possible. Am I imagining that?

EL: I have done two comics I didn’t write, but you are right in saying that I have an auteur take on comics. Comic book storytelling is personal for me. It’s my opportunity to emulate one of my favorite directors — John Carpenter. Carpenter’s work has inspired me for quite some time, and the amount of control that I perceived he had on those movies made a lot of sense to me. Carpenter and Prince had the same approach, and they both made it seem very normal that you would try to do it all if you could.

“John Carpenter and Prince had the same approach, and they both made it seem very normal that you would try to do it all if you could.”

CH: I love that you just put John Carpenter and Prince in the same sentence.

EL: Well, they have a lot in common weirdly enough at least in my mind. Maybe it was a reflection of times they were coming up in, this need to be an auteur creative.

CH: Bringing it back to ALMIGHTY - where did the idea originate and why did you, as an artist, feel compelled to tell this story?

EL: I was originally going to do another story called BLAU. I had been working that out for many years, but by the time I felt that I was ready to do it, BLAU had become too precious to me, and the creating of it became stiff. I thought maybe I should do another story connected to BLAU, where I could figure out a bunch of things without getting wrapped up in whether I was doing the BLAU idea justice. So, ALMIGHTY was a testing ground that would allow me to find how I wanted to tell the story so for instance I discovered while redrawing the first nine pages of ALMIGHTY nine times that instead of the traditional comic book layout it would be better if I formatted the pages as a series of storyboards from page to page.

CH: It’s an idea — ALMIGHTY — it’s an idea you’ve been kicking around for a while, if I remember correctly. I mean, one you’ve been developing for a long time.

EL: Since 2007, before you and I even met. In this case, I self-published it in 2008, in fact.

CH: But you couldn’t let it go. Is that common for you, to work on ideas for a decade or more? And when do you know the idea is ready?

EL: Yeah, it is because when I was younger I didn’t know how to draw all I had was my imagination, and now that I’m older and have developed as an artist, I can go back and tap into it and flesh out something completely original and not heavily derived from the current times.

“There’s another part of it … a Black man has been here first, a Black man of Haitian descent first generation born in the US has been here. Now, come and see what he has wrought.”

CH: Thinking about how long you’ve been working on ALMIGHTY, that means it precedes a lot of the post-apocalyptic cinema and TV that’s come out since you first brought it up — MAD MAX: FURY ROAD, for example, and “THE LAST OF US” most recently. As an artist, I can sometimes shy away from a space that already feels in the zeitgeist, so to say. I second-guess myself, because there’s a part of me, the part that learned how to sell ideas in Hollywood, that worries about comparisons. But I know you pushed through that yourself. What is it about ALMIGHTY that compelled you to keep working on it?

EL: First, let me say I love FURY ROAD and THE LAST OF US games. I just played LAST OF US two a few months ago, and I can honestly say it was the best video game I’ve ever played. Now, I haven’t watched the series yet but people are frothing at the mouth at how great it is, and I can’t wait to see it, but I have to get through this Russian show on Netflix I’m really engrossed in called “BETTER THAN US”. It’s a great show, and it’s tapping into zeitgeist of automation and humans being replaced by artificial intelligence. That being said, putting out a redux of ALMIGHTY is just me saying, “Hey, I was here first, I’ve got the receipts, and the reviews to prove it.” Not saying they are carbon copies of my work. All I’m saying is, if I was in a general meeting with the studio that made those, they would say, “We already got something like that.” Also, there’s another part of it, something that doesn’t really sit in the front my artistic expressions or the way I move through life, but something important and poignant nonetheless — a Black man has been here first, a Black man of Haitian descent first generation born in the US has been here. Now, come and see what he has wrought.

CH: Thanks for the conversation, brother. It’s been too long since we went deep into craft and process like this. Hopefully the next time is in person.

You can learn more about Ed Laroche and his work at his website. You can read more about ALMIGHTY here or find it at your local U.S. comic book shop (in the U.K., I suggest Forbidden Planet).

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: