Q&A: Director Clay Kaytis on Nostalgia, the Holidays, and Finding Himself in His Work

The filmmaker behind THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES, A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS, and Peanuts holiday specials knows a thing or two about the narrative risks involved in mining our childhoods

When the news broke that Peter Billingsley intended to return to play Ralphie all growns’d up in a sequel to the beloved holiday film A CHRISTMAS STORY (1983), my reaction was a resigned shrug. Hollywood is going to Hollywood, after all, its only interest in profit - which all too often means monetizing our nostalgia. To be fair, that’s not wholly unlike what author Jean Shepherd had done when he wrote the novel that A CHRISTMAS STORY is based on, drawing upon his nostalgia for the innocence of his childhood and, of course, Red Ryder BB guns. It’s a film that has stood the test of time — four decades now — because it feels so true to so many of our experiences.

But here comes the twist: A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS (2022), the sequel in question, turns out to be a wonderful, moving film in its own right that both respects and distinguishes itself from its predecessor. Co-written by Clay Kaytis and Nick Schenk and directed by Clay, it somehow manages to recreate a bit of the magic of A CHRISTMAS STORY by wondering what would happen when little Ralphie finally became The Old Man himself and was faced with trying — in a lovely meta-spin — recreate a bit of the magic of his childhood for his own kids.

This isn’t Clay’s first time at the nostalgia rodeo, as I discovered as soon as I finished watching the film and looked up whoever the hell pulled off this Christmas miracle. He’d actually directed another holiday film my family enjoyed, THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES (2018), as well as THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE (2016; co-directed with Fergal Reilly) and some truly wonderful PEANUTS specials for Apple. Before this, he’d been an animator at Disney for nineteen years, during which he served as a Head Animator on numerous feature films.

My interest in asking Clay to join me for one of my artist-on-artist conversations was, I’ll admit, wholly self-serving. My parents both died over the past seven years, and similar losses precipitate both CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES and A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS. In particular, the CHRISTMAS STORY sequel had left me choking back tears at several points, as much because of the sense of loss that permeates its running time as my failure to adequately deal with my own grief. I wanted to chat with him about nostalgia, both in our lives and its appeal and peril when telling screen stories.

For screenwriters at any point in their creative journey, I encourage you to pay special attention to Clay’s discussion of how he tackled A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS by mining his own nostalgia (life) as much as possible rather than your nostalgia for the intellectual property in his lap.

COLE HADDON: I don’t discuss this often — in fact, I don’t even think I’ve ever brought it up to my wife — but from a very young age I thought I was going to animate films for Disney. This is a long time ago, of course. I can’t articulate what was really going on in my head at that time, but I can remember this need. It eventually evolved into comic books and cinema for me and now I’m left to imagine some other version of me out there in the multiverse doing what you did for nineteen years of your career. Can you pinpoint where in your life you started to imagine animation was going to become such a part of your life?

CLAY KAYTIS: I wish I had it all figured out when I was a kid, but it wasn’t until I was twenty years old that I ever seriously considered being an animator. Now, looking back, I can’t believe it took me that long to figure out. When I was a kid — and this was back in the days of VHS — we had all the Disney animated films at home in those plastic clamshell cases. My mom loved them and bought each release, so I had been watching them my whole life. But what I was really interested in was monster make-up and creature effects.

CH: Really?

CK: Oh, yeah. I loved AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON. Rick Baker’s werewolf was amazing, specifically the famous transformation scene, but I was more fascinated by his friend Jack’s mutilated face and neck. I’ll never forget those flappy bits of neck flesh when he moved around.

CH: You’re definitely speaking my language now.

CK: And CREEPSHOW was a treasure trove of make-up effects – the undead couple with the cake, the beast in that crate, Stephen King turning into a plant, cockroaches crawling out of that old man’s face. But my true love was the first movie I saw in the theatre – STAR WARS. I grew up reading the Star Wars Fan Club/Lucasfilm newsletter Bantha Tracks and magazines like Starlog, Fangoria, Cinefex, and, of course, Mad magazine.

“As corny as it sounds, I saw how they brought magic and happiness into people’s lives, and that really cemented my respect for the power and potential of Disney animation.”

CH: What changed for you?

CK: As much as I loved monster make-up, I didn’t know how to do it. I would buy mortician’s putty and fake blood at the local magic shop to create fake cuts on my arms and face, but that was about it. I was creative, but I didn’t draw very well, so when we got our first video camera, I would make stop-motion films with my STAR WARS toys. As far as animation went, in high school I loved “REN & STIMPY” and “BEAVIS AND BUTTHEAD”, and I vaguely remember having a weird crush on Ariel from THE LITTLE MERMAID.

CH: Maybe just a little weird.

CK: No, totally normal teenage behavior. I grew up in Orange, California, which is not far from Disneyland, where I had my first two jobs. The first job was selling popcorn and churros at those little carts. Through that, I saw how much the Disney brand, and especially those animated films and characters, meant to people. As corny as it sounds, I saw how they brought magic and happiness into people’s lives, and that really cemented my respect for the power and potential of Disney animation.

CH: What was the second job?

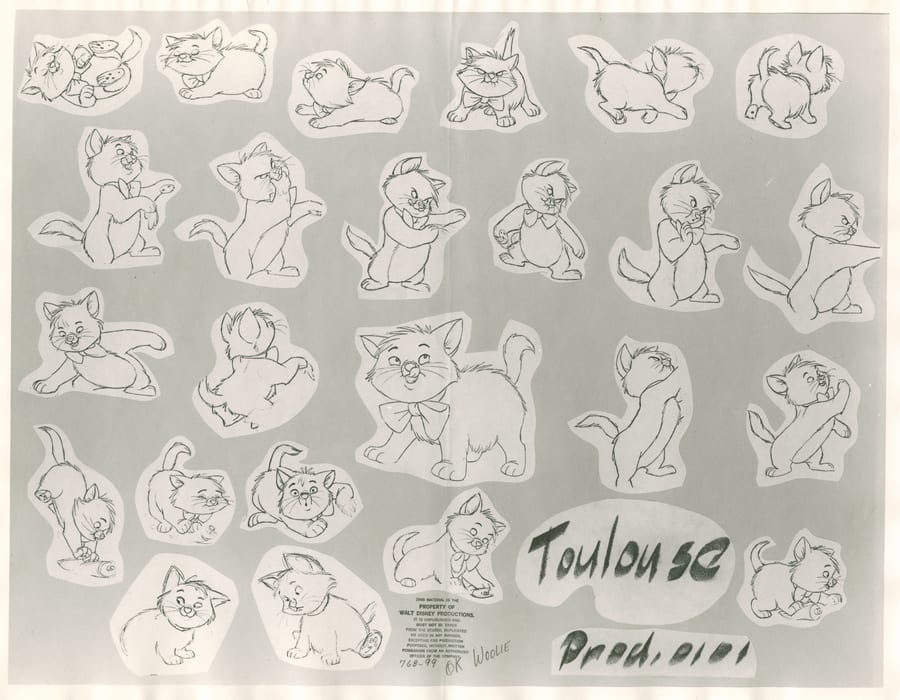

CK: In an art department that no longer exists. I got that job with a portfolio of tee-shirt designs I made for school clubs. They let me paint signs and I became the vinyl lettering-cutter expert. I clearly had an itch for animation because my favorite thing to do in that job was to spend my lunch hours turning through the pages of animated character model sheets they had as reference. I’d try to draw them, but it was hard, they never came out right, and I figured it wasn’t something I could ever do.

CH: So, how did you make the leap to animation, then?

CK: I went to college at USC as a Biological Sciences major. I still laugh about that. But when I took my first college chemistry course, I was so confused, I switched my major to Undeclared. I floated around college for a couple years, eventually switching to a Business major, and I was miserable. I had no idea what to do with my education or my life, and I was racking up insane student loans. My favorite class was in my first year — Introduction to Cinema — but I never applied to the film school because I was honestly too scared.

My mom knew I was miserable, too. While talking to the woman who ran the computer lab at my high school, my mom told her about my misery, as moms do, and the woman — I wish I knew who she was because that woman changed my life — said I might be interested in an animation class she knew about at a local high school. It was a night school course that adults could take, and maybe I’d like it. Somehow, this woman knew more about me than I did.

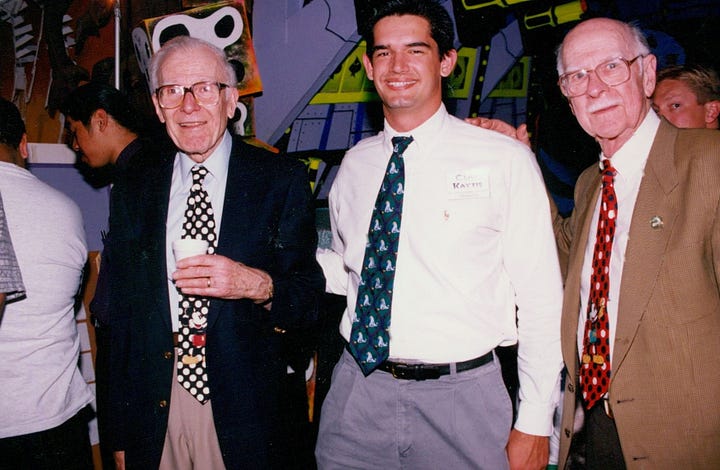

Long story short, I went to this animation class in the fall of 1993, paid my $25 fee, and nine months later, I was a college dropout and an intern at Walt Disney Feature Animation. I left Disney almost twenty years later in 2013.

CH: You mentioned earlier that you didn’t draw very well as a child and then described how difficult it still was when you were working your second job at Disney in a now-defunct art department. But a few years later, you were working in its feature animation department. I’m curious about how you describe this evolution and the work it required to master a craft that you make sound as if didn’t come naturally to you.

CK: “Master” is a word that I wouldn’t apply to myself. The great thing about this animation class was the teacher, Dave Master – his name was actually Master. He was so clear about how it works. He showed us a sample drawing portfolio, which has figure drawings, gesture drawings, and animal drawings. I was truly starting from zero. I went with two other students to every figure drawing class I could find and afford. There was one in a church basement — the models wore leotards — and ASIFA Hollywood, an animation organization, used to have figure drawing on Tuesday nights for five bucks, and then Art Center in Pasadena had workshops on Wednesdays for their students and we’d just walk in like we belonged there. I bought a zoo pass and drew animals every week. Gesture drawing can be done anywhere there are people. I still worked at Disneyland, so I could go in for free and draw tourists.

CK (cont’d): The other half of an animation portfolio is animation, so I was doing animation assignments for the class, all drawn on paper. After nine months I had enough drawings and animation to make a portfolio. It wasn’t good at all, but I had one. In the end, I was told that although other students had better work than mine, mine showed the most growth and that’s why I got a spot. If I could change one thing about my career, I would have started drawing when I was much younger. Starting at twenty, I was decades behind my peers, but I figured it out through pure willpower and sweat - but drawing has never become an easy or enjoyable thing for me.

CH: In 2016, you co-directed THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE with Fergal Reilly, which turned into a massive success and spawned a sequel. I’d like to ask about what followed, because you were finally in the big seat. You got to direct a feature animated film and it was a big hit. What motivated your decision to direct a live-action film as your follow-up rather than sticking with animation?

“I distinctly remember thinking, ‘I could comfortably direct animated films for the rest of my career, or I can try something I’ve never done before.”

CK: The years leading up to THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE were a period of tremendous growth in my creativity and confidence, and I mainly attribute that to taking jobs I was almost qualified for. In every case, I rose to the task, so I kept taking chances and putting myself out there. I supervised my first character, Rhino the hamster in BOLT. I became one of the three Heads of Animation on TANGLED. I pitched and oversaw the creation of the end credits for WRECK-IT RALPH. Then, when I directed THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE with Fergal, I realized that it was not much different from the work I had done in those previous roles - except it was far bigger, with much more responsibility for the final product. I don’t pretend that ANGRY BIRDS was easy or that we achieved some sort of perfection, but I distinctly remember thinking, “I could comfortably direct animated films for the rest of my career, or I can try something I’ve never done before – live-action.” I wanted to find out if I would fail or succeed.

CK (cont’d): It was like a switch was thrown in my brain and I had a new goal. I told my agent, who said it would be hard to make the change. The hard part was turning down work. I was offered a few animated films to direct, and I passed on them. It felt insane to turn down good work, but I was resolved, and stubborn. I think almost a year went by while I read scripts and took meetings, and then I read one called 12-24 by Matt Lieberman, and I knew it would make a great film. That turned into THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES.

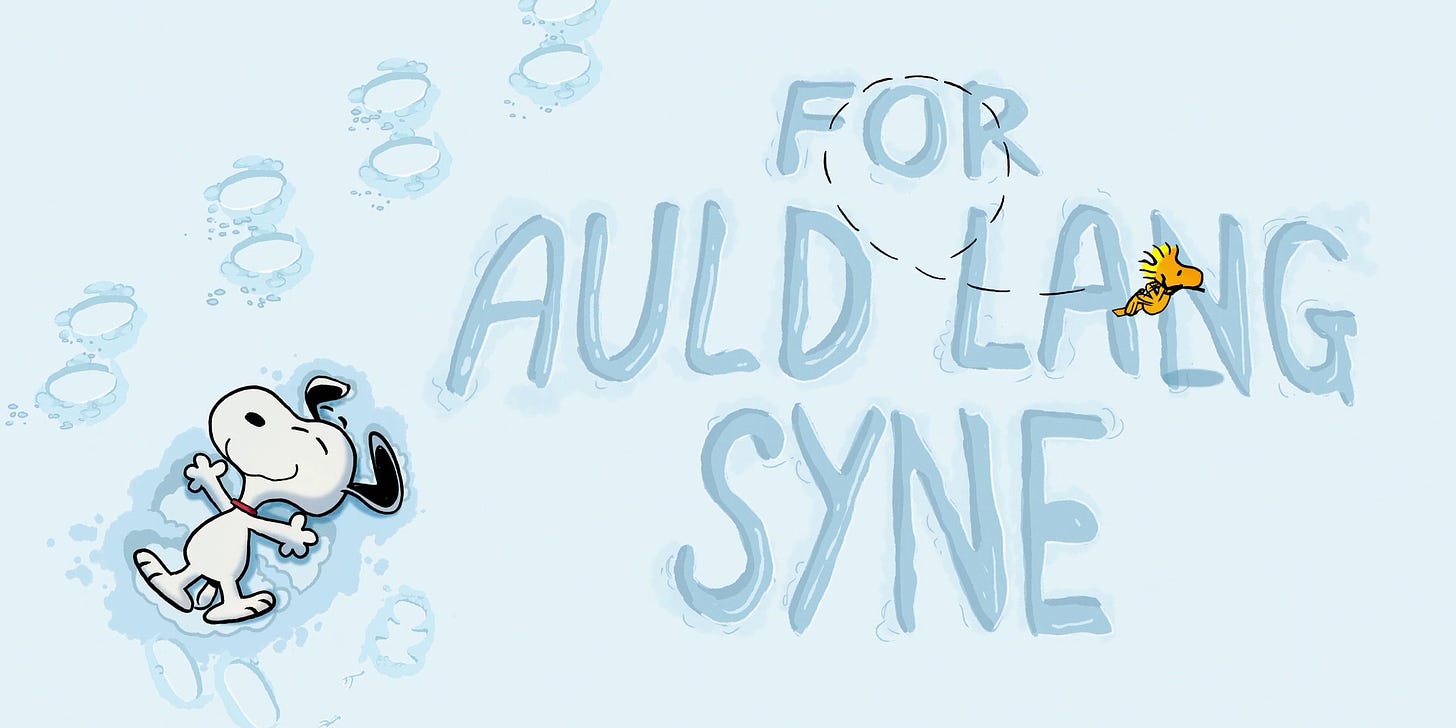

CH: One of the reasons I asked you to join me for this conversation is because of the role of nostalgia in so much of your work, whether intentional or not. It’s certainly reached a crescendo in the last few years with your two SNOOPY PRESENTS films — AULD LANG SYNE and TO MOM (AND DAD), WITH LOVE — and your live-action films THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES and A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS. Before we get more into this subject, at least regarding your art, I’m curious to hear if you would describe yourself as a nostalgic person?

CK: It depends on what you mean by nostalgia. There’s nostalgia for times gone by and there’s nostalgia for things. In either case, I wouldn’t say I’m as nostalgic as much as I’m a person who knows what I love. I think there’s a difference, but maybe I’m wrong. I have friends who can name every toy, animated show, actors in TV series. I’m not like that, except for a few things like STAR WARS, “THE MUPPETS”, or archaic video games. Something I did a few years ago — which I highly recommend — was to make a “mood board” of all my influences. It gave me some clarity when I was trying to figure out the types of films and entertainment I should be making. It’s the type of stuff I loved. I want to make films that kids will remember when they’re grown up.

CH: That’s such a great way to phrase it. I’m going to steal it, if you don’t mind.

CK: Steal away! I would imagine many creatives are led by that thought whether they realize it or not.

CH: So, what about “times gone by”? THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES is certainly steeped in it, as much as it is grief. The same can be said about A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS, which we’ll get more into in a moment. You’re not one of those people who long for what was at the holidays?

CK: “What was” at the holidays never really changes, does it? I hope not. It’s being with family, expectations, eating, fighting, laughing. Circumstances in life change that, might make it harder to get together, but holidays are a universal experience. And I’m not strictly talking about Christmas here. This applies to any times we remember spending with our families.

“It was more important to me to recreate that feeling than anything else.”

CH: You’re not wrong. My grandparents and parents are gone. My siblings and I are scattered to the wind. I miss what was more and more every holiday, but the yearly ritual of being with my wife and kids — my family now — has simply replaced that. Life goes on – but I still find it impossible to let go of what was.

CK: I know that scattered feeling all too well, and it makes us appreciate those times even more, doesn’t it?

CH: Absolutely. One of the dangers of working with stories steeped in nostalgia, as I described it — a subject I’m clearly fixated on in my personal life — is that the nostalgia can become the reason for the story rather than offering anything new to say. How have you managed to avoid that?

CK: Well, look at the PEANUTS specials I did. Growing up, I liked Snoopy — who doesn’t? — but I was never obsessed with PEANUTS. When I made mine, I focused on the memory of how those old PEANUTS specials made me feel as a kid. It was more important to me to recreate that feeling than anything else.

CK (cont’d): Because of that, I felt guided by intuition more than on any previous project. I defended what I felt were the right instinctual choices and I think those are the moments that touched the audience the most. I came out of those SNOOPY PRESENTS with more confidence than ever before. It was a creative shift for me to be less logical, although I will never lose that, and rely more on my heart. It sounds silly to say that out loud, but I’m learning that’s the key to real creativity.

I think what can happen to a franchise after decades of iteration is that the stakeholders lose sight of experiencing it for the first time, or they never had it because they are so close to it. I saw that happen to me at Disney. The more you know how the sausage is made, the less enjoyable it can be. And I don’t mean the work was unenjoyable, but being able to go to the movies and experience the latest Disney animated film for the first time was something I essentially gave up in making them. So, sometimes it takes an outsider to come in and say, “This is what this means to me.”

CH: What about A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS? As you know, I’m a huge fan of it. You and the whole team managed an impossible feat with it, as far as I’m concerned.

CK: Thanks, that’s so nice to hear. With A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS, it was almost the same, but I have such a love for the original film along with millions of other people, and I really didn’t want to screw it up. I do think A CHRISTMAS STORY is one of the greatest movies ever, and I had probably seen it over thirty times in my life. Doing the sequel started as more of a forensic exercise, carefully examining every element of the original to figure out why it is so brilliant. Peter Billingsley and I talked a lot about the fact that we were walking on hallowed ground. The nostalgia came into play in honoring Jean Shepherd’s voice, my memories of growing up in the seventies, and the feelings I’ve experienced through my Christmases.

CH: Can you talk about how you avoided missteps in this regard? It would’ve been so easy to slip into fan service, I supposed you could call it – something that feels good based on the original but rings false in the context of the sequel.

CK: Well, I am not a big fan of fan service. I think that has sort of poisoned the well in a lot of properties and taken the place of actual storytelling.

“It’s like the people making these things are asking themselves what would get a dopamine reaction instead of what existing elements could still be relevant to this new story.”

CH: I’m so glad to hear you say that. I find it infuriatingly lazy.

CK: It’s like the people making these things are asking themselves what would get a dopamine reaction instead of what existing elements could still be relevant to this new story. Peter and I talked a lot about playing offense and defense on this film, because we had to move it forward but not so far that it felt like it existed in a different world. Of course, we got the expected request to bring back the leg lamp, but we held firm. Plus, I would point out to them that The Old Man buried it in the backyard to the sound of “Taps”. So, no, it’s gone. But when we did put some Easter-eggy things in, we always tried to find a way for them to add to the story.

CH: I imagine a lot of your approach was determined by the fact that Ralphie is now the age — well, the same age-ish — of The Old Man in A CHRISTMAS STORY.

CK: Yes, this story is told from the perspective of Ralphie as an adult, so none of those things mean the same thing to him that they once did, for better or worse. It was fun to look at something as iconic as Higbee’s and show what it’s like from the parent’s point of view. Simply rehashing gags was not going to make the cut.

Even with so much established from the first film, I found that the more personal I made it, the easier it was to tell this story. My mom passed away when I was filming THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES and so much of my family’s first Christmas without her informed my decisions on A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS.

CH: I’m sorry to hear your mother is no longer with us, but I appreciate how that first Christmas without her influenced A CHRISTMAS STORY CHRISTMAS. I still remember my first Christmas without my mother, and it’s one of the reasons your film spoke to me so much.

“Even with so much established from the first film, I found that the more personal I made it, the easier it was to tell this story.”

CK: Yes, it’s never the same after that. This seems like a good place to tell this story that I’ve never really talked about. It goes with that idea of relying on my own experience and learning to trust my intuition.

CH: Okay, I’m intrigued.

CK: First, “spoiler alert” for readers – if you haven’t seen the movie, go watch it, then come back. Okay, When I was young, my mom bought a birthday present for my grandfather that she knew he would love, but he died before his birthday and never received the gift. This was something she regretted for the rest of her life. After that, she couldn’t hold onto gifts for more than a couple months. If, during the summer, she found something we’d like, she’d give it to us then and find something else to get us for Christmas.

This was one of those memories I knew I had to fit into the movie, with a little change, so I decided that The Old Man would save this terrible Christmas, even after his death, by giving everyone the perfect gift. The only problem was figuring out how that would work. I wrote one version where the kids find the gifts in the shed. No one really responded to that. Then I tried a version where the gifts were packed in the trunk of the car. Not much love for that one either. I was determined to make this work, so I wrote a third version where The Old Man had stashed the wrapped gifts in the basement. The trick was having a reason for someone to find them right before Christmas morning. So, I relied on some of that nostalgia we’re talking about. While Ralphie and his mom are sitting by the tree on Christmas Eve, I realized blowing the fuse was perfect. Mom fixes the fuse, finds the gifts, and voila - Christmas is saved. Even within that, there’s a line I wrote to justify why she’s going to fix the fuse. She says “No, I need to learn to do these things on my own,” which is such a painful truth that so many people have responded to.

CH: I’m one of them. I winced at that line.

CK: Whenever anyone tells me they cry watching the film, it’s at the moment when the family sees these gifts from The Old Man. I’m so proud of this for so many reasons. It’s unexpected, it’s organic to the story, it’s a nod to the original film in more than a few ways, it’s from one of my most personal memories and I knew it would connect with the audience, and I didn’t give up on it. It’s the single most rewarding experience I’ve had in trusting my instincts, and I honestly can’t wait to do that trick some more, so I can keep chasing that feeling. It’s so damn validating, and honestly addictive, to pull off something like that. Writing can be a truly magic experience sometimes.

Subscribe to Clay Kaytis’s Substack Frame By Frame.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

My debut novel PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: