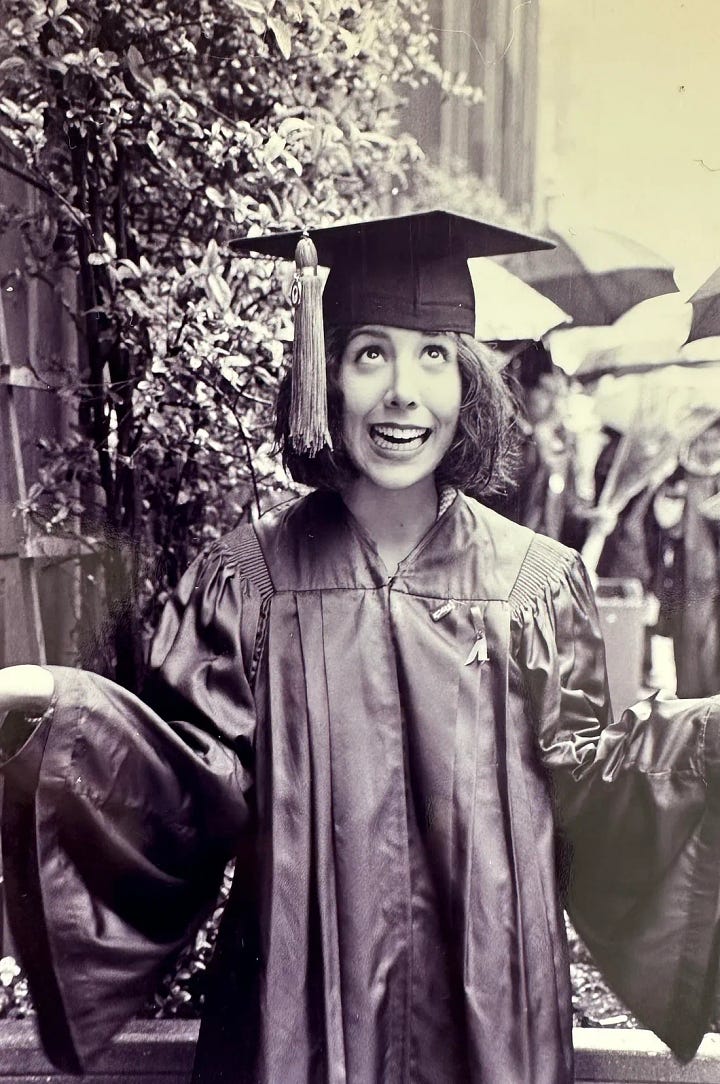

Q&A: Dailyn Rodriguez on the Challenges She Had to Overcome to Become a Successful TV Showrunner

'THE LINCOLN LAWYER' is back, so I asked its showrunner to chart her journey from daughter of a member of the Cuban Mafia to TV’s biggest job

When I started my artist interview series, it wasn’t just to spend a lot of time talking shop with artist friends. I also wanted to get to know people I had previously only admired through their work. This was the case with TV showrunner Dailyn Rodriguez when she agreed to take our passing Twitter relationship to the next level by opening up to me about her life and career.

Usually when someone agrees to do this with me, it doesn’t include reminiscences about their mafia dad, but it turns out Dailyn’s childhood would make for television as thrilling as what she has put on screens in the past few years as showrunner of the fourth and fifth seasons of “QUEEN OF THE SOUTH” and the second season of “THE LINCOLN LAWYER” (our July 6th).

In our conversation, she and I discuss her early life in Washington Heights, her work and style as a showrunner, and the challenges Hollywood’s systemic racism and sexism posed for her career ambitions.

COLE HADDON: Let’s travel back in time, metaphorically speaking. Are you ready?

DAILYN RODRIGUEZ: Oh boy! I hope you’re ready.

CH: You grew up in Washington Heights. Tell me what that feels like in your memories.

DR: It feels like the beginning of summer. I’ll try to explain…

I have so many memories of it being hot and humid and kids opening up fire hydrants in the middle of the street. The best part of growing up there was the freedom I had as a kid. Getting a slice and an Italian ice at the local pizzeria after school. I loved the energy of being in Manhattan. Honking cars. People yelling up from the street to open windows, looking for their friends to come down and hang out. Dominican, Cuban, and Puerto Rican men playing dominos on the street. [The] green lint sticking between my toes from the wool socks I had to wear with my Catholic School uniform. I got to take break dancing in gym class. And every Sunday my whole family, including my extended family, would go to this great Chino/Latino restaurant called La Perla Oriental. We’d get fried rice and fried plantains — perfect Cuban and Chinese mix.

CH: You’re making a strong case for growing up in Washington Heights. So, what was the worst part of growing up there?

DR: The worst part of living in the Heights in the early eighties was when the neighborhood took a turn for the worse. Crime skyrocketed. The Bronx was burning. Also, Cole, you may have found this in your research — my father was in the Cuban mafia. Members of the Lucchese crime family were at my sister’s Quinceañera.

I had a bodyguard, named Fidel, who would show up every morning and walk me to St. Elizabeth’s. My Dad was shot. Luckily, he survived. My cousin was murdered.

CH: That doesn’t sound at all — you know — insane.

DR: Oh, it was absolutely insane. I mean, my sister was almost kidnapped walking home from school. So, my mom stopped walking me to school. Instead, I had a bodyguard, named Fidel, who would show up every morning and walk me to St. Elizabeth’s. My Dad was shot. Luckily, he survived. My cousin was murdered. My sister’s best friend’s parents had a flower shop and were held up at gunpoint. Her mom was killed. So, the last few years in the Heights weren’t the greatest.

CH: I take it back. Wow, that is…kind of a TV series I want to see you write now.

DR: I might be going out to pitch something about this world. We shall see.

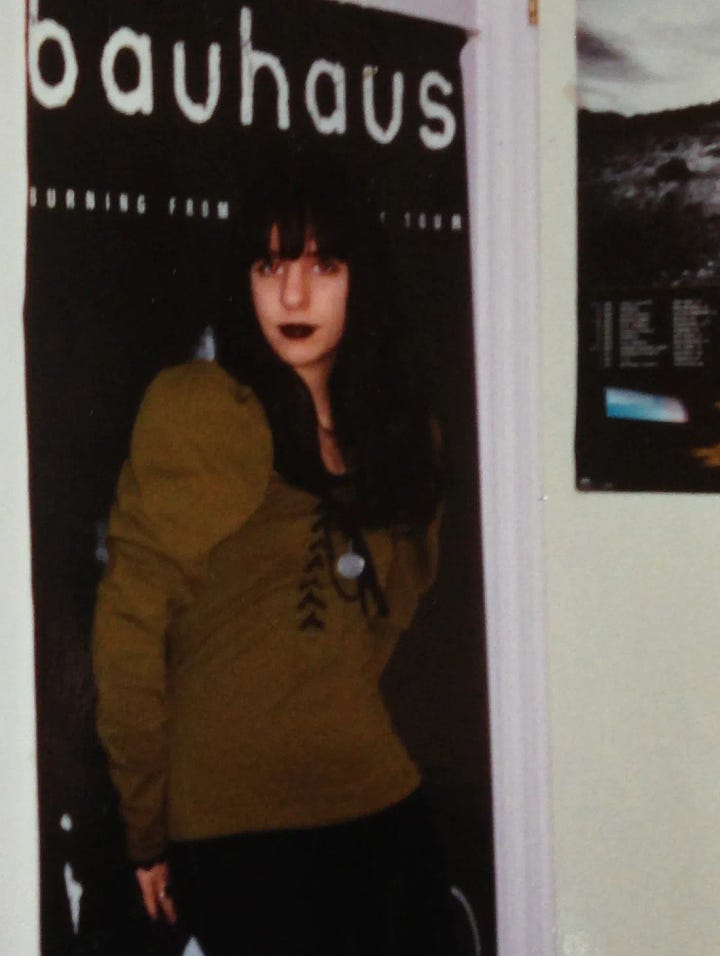

CH: What was your relationship to the arts at this time? What was the popular culture you were primarily exposed to, that shaped your early creative identity?

DR: I watched a lot of TV. I basically learned English from “SESAME STREET” and “THE ELECTRIC COMPANY”. My mother was having a hard time because my father left us when I was five, so she would plop me in front of the TV all the time. The series that really spoke to me were urban Black sitcoms like “WHAT’S HAPPENING?”, “GOOD TIMES”, “SANFORD AND SON”. Any urban series, actually. There was also a sitcom on PBS called “QUE PASA, USA?” It was bilingual and created to help new Latino immigrants learn English. That was the first time I saw a family like mine on TV. When we I was nine, we moved to New Jersey, and I started to learn about theatre and plays. I was Juliet in our 6th grade play. I got the theatre bug then and all through high school.

CH: Was theatre what took you to NYU and Tisch then, or did you already have your eyes set on Hollywood and film/TV at that point?

DR: I had a drama teacher in high school who really become a mentor to me. He started an actor/playwright workshop and an original one act play festival. I wrote four one acts in high school, and ended up a winning a competition with Baker’s Plays out of Boston (Baker’s was bought by Samuel French, and they were just bought by Concord). When I was seventeen, they published all my plays in my own collection. I’ve had productions in a bunch of high schools all over the world — it’s pretty cool. I was writing plays, but I was also acting. I applied to Tisch Drama for early admission. I got in and, after a semester, I transferred to the Dramatic Writing department. I realized that I wasn’t meant to be an actor. I missed being around writers.

CH: Hollywood classism is something that’s always frustrated me, how nobody talks about how most of the people who make it as screenwriters, directors, producers and execs, agents — I could go on — come from so much privilege. Were there many Dailyn Rodriguezes around you at college, from their own Washington Heights, with mafia dads or the equivalent? Basically, were you able to live openly as yourself, or did you try to adjust, mask some of that background to stand out less?

I spent my high school years hiding what my Dad did for a living from most of my friends. But once I left for college and then for Hollywood, I decided it was only useful to me to be honest about my background.

DR: I’m pretty certain I was the only Latina in my program at NYU. If there was another Latina or Latino, I never had a Dramatic Writing class with them. I don’t hide my background at all. It’s what makes me who I am. I spent my high school years hiding what my Dad did for a living from most of my friends. But once I left for college and then for Hollywood, I decided it was only useful to me to be honest about my background. As you can imagine, Cole, I give good meeting because of this mafia history.

CH: Oh, trust me, I am jealous. Reps will tell you to try to hook executives with one interesting thing about you, something they won’t be able to forget. Yours is one of the best “hooks” I’ve ever heard.

DR: Yeah, it stops people in their tracks. Sometimes, I wonder if they believe me. But you can google my dad, it’s true. I also have a really dark sense of humor about my childhood, and I think that puts most people at ease with the violence and trauma.

What’s the one interesting thing about you, Cole, that you use to hook people in a meeting?

CH: Oh, I’m a fictitious person. When I was twenty-nine, I manufactured a resumé that claimed I was a successful film and music journalist. I also made up a new last name — Haddon is a nom de plume. Both got me a ton of work, and within a year I was writing for more than twenty papers around the States. This came with a lot of anecdotes about fraternizing with notable artists that featured details like, “And that’s when the cocaine delivery guy showed up!” These days, I’m just the asshole who moved overseas, away from Hollywood at the height of his career, so I get to answer lots of questions about what it’s like to put my happiness over my professional success.

DR: [Laughter] First of all, you’ve got to do what you‘ve got to do. I’ve heard stories of actors pretending to be their own managers to get auditions. Also, are you an asshole…or a genius?

CH: Probably both. So, how did you find Hollywood compared to Washington Heights and NYU? I’m always curious how artists find their footing in L.A., especially when they come from such different cities and communities. My first year was especially jarring. I lived in Echo Lake. The hipsters there just seemed so silly to me. Later, when I broke into the business, I found it all performative; everyone seemed to be playing badly written parts in scripts to me. It wasn’t until I realized I had to remove people from their offices and business lunches that I could learn who the real them were.

DR: When I first moved to LA, I had issues with how passive-aggressive people can be. Coming from New York, I am very direct. So, I think sometimes I may have rubbed people the wrong way. I just don’t like to bullshit, and I don’t have time for bullshit.

That being said, I’ve made wonderful friendships and creative partnerships. You just have to search for your tribe out here. I’m part of this wonderful group of Latina writers who are activists for Latin representation in Hollywood and that’s been really galvanizing. We have a lot of work to do to achieve adequate representation.

CH: There’s such a stark difference between being a staff writer and a writer-producer, but especially a showrunner on a TV series. That no-bullshit life approach can really bite you in the ass in those collaborative environments, and certainly when you have to start navigating the world of studio, network, and streaming overlords who pay the bills. Can you talk about the difference between Dailyn the Staff Writer and Dailyn the Team Leader? Tell me what came naturally and what you had to force yourself to evolve into so you could succeed.

DR: If I can go back in time and talk to Dailyn the Staff Writer, I would tell her to chill the fuck out. I would say that her entire job is to help the showrunner, to make his or her job easier. If you turned in an outline and three days later you’ve had no response from the showrunner, and then they walk past you in the hallway and don’t make eye contact, it probably has nothing to do with you or your outline. It’s probably because they’re worried about twenty million things more important than you.

That being said, as a showrunner I try really hard to communicate with my staff. I like to let everyone know where I am in the process with their material, so they can feel more at ease. I’m very aware of my staff’s egos and their feelings because I still remember feeling so nervous and lost, hoping I was doing a good job and constantly thinking I’d get fired for something minor.

Now that I’m a showrunner, I start every first day in the writers’ room with a speech about this. I tell everyone that we all need to leave our egos outside the room, that their main job is to help me stay on schedule, keep the trains running on time and on the track. Don’t derail the work. I try to let my staff have creative freedom when we are breaking a season arc, but at some point, as the team leader I have to make decisions and that’s just the role of a benevolent dictator. That’s what I consider myself. A benevolent dictator.

This is the best way I’ve found to explain the job: a showrunner is the Chief Creative Officer (CCO) of a multimillion-dollar company. I am the boss of all the creative departments.

CH: For readers who aren’t entirely aware of what a showrunner does and others outside of the States who might have a fantasy version of it in their heads, how would you describe the role of a U.S. showrunner?

DR: This is the best way I’ve found to explain the job: a showrunner is the Chief Creative Officer (CCO) of a multimillion-dollar company. I am the boss of all the creative departments. I oversee all creative decisions in the company, and I use the money given to me by the studio overlords to make it all happen on time and on budget. It’s mostly a creative job, but it also involves technical and monetary responsibilities and everything I do has to be okayed by the studio and the network or streamer. I still have bosses above me.

CH: One of the aspects of being a showrunner that has consistently deterred me from coveting the title is how so much of the job is about being an administrator. Most of the time, I just want to sit in my boxers and write whatever inspires me that day and the prospect of doing the opposite for a season is just too much for me. That said, all my showrunner friends love their jobs and seem creatively tortured when they’re not on a show doing it. What do you get from the experience that gets you excited when you wake up every day?

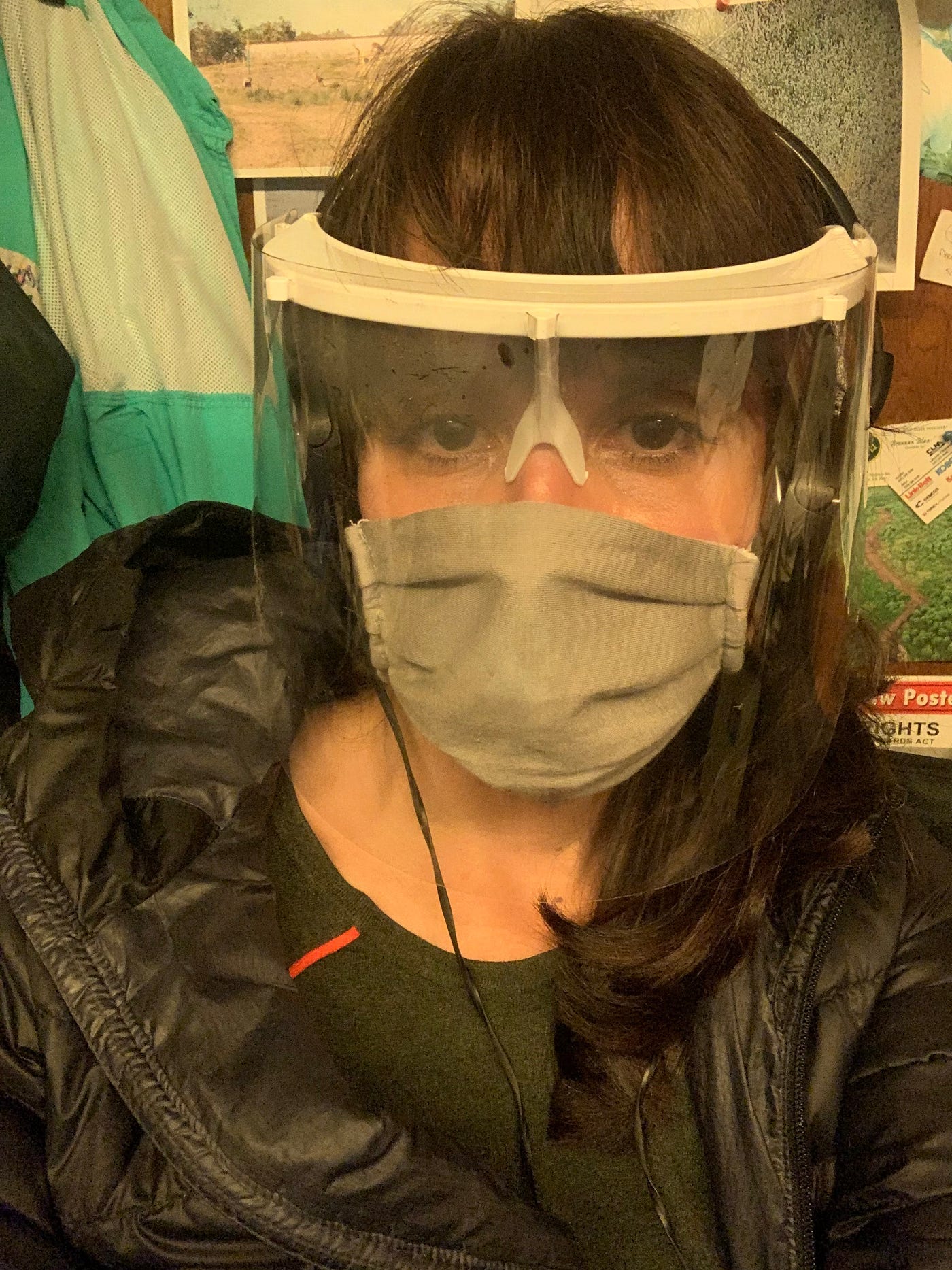

DR: I love collaboration. I’m an extrovert, and I don’t like sitting in my office by myself with my thoughts for long periods. I like throwing ideas around with other people. I’m also not a control freak about the script. I really enjoy seeing what the department heads come up with that may enhance the script or change it in a way that is surprising and interesting. I love when an actor comes up with something a little cleverer than what was on the page. Or a director looks at a scene and brings something to it visually that I didn’t even imagine. Don’t get me wrong, this job is fucking hard. It can consume you if you let it. But I delegate and let people take charge in their respective roles. Also, I don’t really need to interrupt my dinner to look at wardrobe. It can wait a minute. It’s about work-life balance, and I feel like I’m good at that. It probably has to do with how late in my career I became as showrunner. Being a woman and Latina, it took me a little longer than the average writer. Seventeen years, to be exact.

CH: Can you unpack that last statement for anyone who hasn’t landed in Hollywood yet, or have, but have their heads shoved up their own asses? I know it’s a big question, but how have your creative ambitions in the film/TV business been complicated because of your gender and non-white identity?

DR: I broke into TV writing through the Walt Disney Studio TV writing fellowship, which was amazing. However, there is a contingent of people in the business who see the writers who come out of “diversity” fellowships and programs as “less than”. You get a little stink on you. On top of that, it’s pretty common for “diverse” or “minority” — I hate both of these words — writers to get stuck repeating staff writer position for multiple years.

Just so people understand, a staff writer is an entry level position in a writers’ room. If you are made to repeat this level, it means that you don’t get paid for any scripts you write — this is a terrible provision in the WGA’s contract with the studios and every time negotiations come up the Guild tries to do away with it. So, it’s a low-paying position, and “minority” or “POC” writers are more often hired as staff writers. And if they constantly repeat this level, they don’t move up the ladder in the room, and their income stagnates as do their careers. So, I repeated staff writer three times and the second level, story editor, twice.

CH: Fuck me.

DR: I was constantly the only Latin person or one of two Latin people on a series. I started to feel like I was being tokenized by my agents at the time. I was only being put up for Latin shows. I haven’t even started to talk about hearing things from my representation like, “Sorry, but they already hired their diverse writer on that show.” Or, “They already hired a woman.” Basically, admitting that one woman was enough or one diverse writer was enough for a writing staff.

Anyway, I went up the ladder slowly, and I finally became a showrunner because the showrunner on “QUEEN OF THE SOUTH” wanted to leave, and I was the natural successor. However, as a woman who hadn’t done the job before, but had seventeen years of TV experience, I was asked to take on a co-showrunner. How do you like that story, Cole?

CH: What infuriates me is how it’s just a variant of dozens of other similar stories I’ve heard from people of color and women of any kind.

CH (cont’d): Okay, last question. How present is that little girl from Washington Heights — the Latina looking for herself on screens, the burgeoning storyteller surrounded by energy and life and violence — how present is she in the writers’ room every day, when you sit down at your laptop to type, when you consider what stories to tell and how to tell them?

DR: After this period in my career when I felt like a token, I left my agency and signed on with new reps. I told those reps that I really wanted them to put me on the “whitest” show on TV — and they got me an interview on the reboot of “BEVERLY HILLS, 90210". I got that job, then every subsequent job after that one had little-to-no Latin characters or storylines, until I wrote on “THE NIGHT SHIFT” on ABC. And then, I started to see all these pilots being greenlit with Latin casts, and most of those stories were being written by white men. I didn’t like that other people were telling those stories, and I was mad at myself that I had given up on them. I realized that I wanted to write about my community, my ethnicity, my family, my culture. So, I told my agent that I wanted to develop in the Latin space, and since then I’ve sold and written five pilots set in a predominantly Latinx/e world — and I’ve written on two shows with Latin leads.

I can’t ignore that, ultimately, when I look at the page, the Cuban New York/New Jersey Mafia kid is always going to come out somehow.

I realized that I was ignoring my voice. I was allowing a few bad experiences in Hollywood to dictate what I was writing and the kinds of series I wanted to pursue. I’m a writer, and I can write a lot of different stories. Medical shows, cops, shows, teens, etcetera, etcetera. I’ve proven that already. But I can’t ignore that, ultimately, when I look at the page, the Cuban New York/New Jersey Mafia kid is always going to come out somehow.

DR (cont’d): One last anecdote. There was someone in the industry that shit-talked about me to a showrunner. Apparently, this person thought I was “difficult” in the room. I was a little shocked because I’ve always thought of myself as a team player. But, I am also aware that I don’t like bullshit and I’m pretty direct. Remember, what I said about passive-aggressive people in L.A.? Anyway, my agent called me one day because it appeared that I was starting to get a little bit of a reputation because of this person. My agent asked, “I’m trying to fix this problem. What should I say about you when I pitch you to showrunners?” And I said, “I don’t suffer fools. I’m a direct person. Tell them I’m from New York, and if they don’t like any of those traits, then I’m not the writer for them.”

I’ve got to be true to myself. If I don’t present my authentic self to the world, then how will I be authentic on the page?

Season 2 of “THE LINCOLN LAWYER” will premiere on Netflix on July 6th, 2023. You can find Dailyn Rodriguez on Twitter.

If this article added anything to your life, please consider buying me a coffee so I can keep this newsletter free for everyone.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Enjoyed this interview to the moon! Dailyn is my hero.