Q&A: Author Louis Bayard Is Stuck in the Past

The novelist behind 'The Pale Blue Eye' and, more recently, 'The Wildes' discusses the evolution of his writing career, Hollywood adaptations of his work, and why he prefers history to the present

“I think you’re going to love it, man,” the producer Anthony Mastromauro told me right before he mailed me a copy of the novel Mr. Timothy. This was back in 2008, when I was still living in Hollywood. “It’s set in Victorian England, it’s bloody, it’s funny, it’s Dickens — kind of — and it’s set at Christmas!”

This is how I discovered the author Louis Bayard.

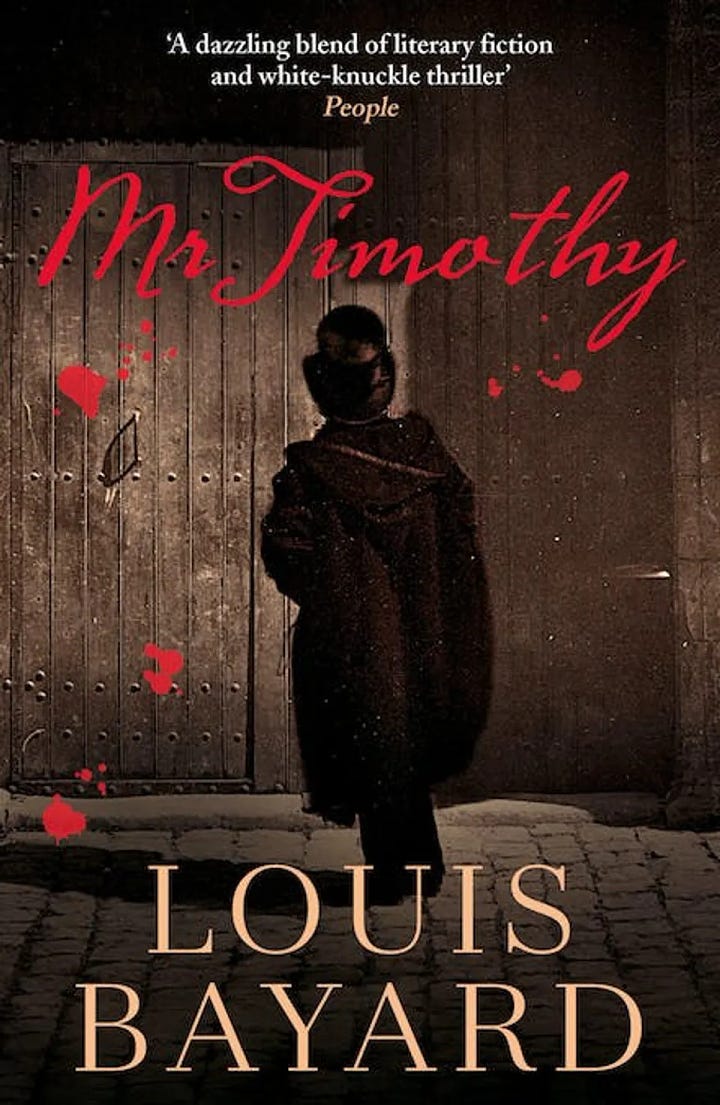

Mr. Timothy, published in 2003, is about Charles Dickens’s Tiny Tim all grown up and condemned to rediscover his own decency during an especially violent Christmas season, not dissimilar from what had happened to his now-benevolent “Uncle” Scrooge many years earlier. A gothic mystery plays out that, while very clearly R-rated — prostitutes, sex trafficking, girls imprisoned in coffins — makes for one hell of a life-affirming Christmas story.

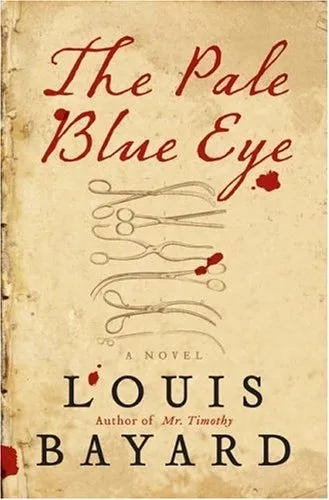

Anthony was not wrong. I tore through Mr. Timothy, loving every page of it. He and I quickly determined to adapt the novel as a feature film, a mission that has unfortunately dragged on for more than a decade now. Louis’s follow-up, The Pale Blue Eye (2006) — this time pairing a fictional detective with the real-life Edgar Allan Poe to solve a series of grisly murders at a military academy — has been more successful in making the leap to the big screen (though the journey was almost as long). A couple of Decembers ago, it debuted on Netflix, written and directed by Scott Cooper and starring Christian Bale and Harry Melling, where it was an immediate hit. I’m far from surprised. The mix of mystery, horror, and history and/or literary history that define Louis’s earliest novels — or, rather, his early historical novels that followed a pivot in his career — is wildly entertaining.

Given the success of The Pale Blue Eye adaptation and his latest novel Jackie & Me (2022) and, most recently, The Wildes: A Novel in Five Acts (2024) — both of which couldn’t be further from the bloody tales Louis spun in the Aughts — I thought it would be a good time to have one of my artist-on-artist conversations with him.

COLE HADDON: You like to take readers back in time in your novels, Louis. Take me back in time in your own life, but hopefully with less bloodshed than I’m accustomed to from your work. What was the first piece of art — story, image, song, whatever — that you can remember igniting your imagination?

LOUIS BAYARD: Knowing how much this ages me…my earliest movie memory is of watching True Grit (1969) in a theater. Specifically, the moment where Mattie is accidentally dragged into a rattlesnake pit. This really got my attention, not just because I’m terrified of snakes, but because of the astounding speed with which it happened. One second, she’s above ground; the next, she’s below. I reacted the way you would to a magic trick. How did they do that? I think that was one of my first inklings of what a storyteller can do.

By the way, because I’m an idiot, I waited another four decades to read Charles Portis’s novel — which is pure genius and which has one of the best fictional voices I’ve ever read.

CH: Can you also recall when you became conscious of the fact that you might want to spend your life telling stories?

LB: I remember regaling my classmates in 5th grade with stories about Brian Walker up the street. He was my friend Kevin’s littlest brother, and I can’t say why I chose him, unless it was just that I didn’t know him very well and nobody else in class knew him at all. But I began to improvise these increasingly wild tales about him. I remember how gratifying it was to hear my classmates laugh, to have the gift of their attention. One of the more intelligent classmates made inquiries into the real Brian, and learned that none of it was true, and confronted me on the playground. I thought I was done for, but my friend Hugh, bless him forever, thrust out his head like a turtle and bellowed, “They’re good stories!” So, there you are. It’s Hugh’s fault.

CH: You’ve published numerous books at this point in your writing career. You’ve received more than a little critical acclaim. And not quite two years ago, a film adaptation of one of your most popular novels, The Pale Blue Eye, dropped on Netflix, starring Christian Bale and a host of other great, sometimes legendary actors starring. Juxtapose who you are as a writer today with that young playground storyteller, with all his dreams and ambitions soon to follow. What do you think that kid would make of the career you forged for yourself or even the success of The Pale Blue Eye?

LB: I should admit that little kid had a certain amount of misplaced ambition. He idolized Twain and Dickens, and thought he wouldn’t mind being like them, having no real idea of what that entailed. But he was also mad for old movies — the older the better — so the thought of somehow spawning a movie would probably have seemed out of reach because, to him, movies were the golden road. I see, too, that my ambition can’t be divided necessarily from my parents’ ambitions for me, and so the fact that neither parent is around to see all this creates a little space of sadness. There is also the curious displacement of being congratulated for your success when the book in question — The Pale Blue Eye — was written more than fifteen years ago. All that said, it’s a wonderful experience to have one’s work sent out into the world, and I’m grateful, and I wish other authors could know it.

CH: You referenced your parents’ expectations. Mr. Timothy is about a child failing, or maybe I should say striving to live up to his parents’ expectations. Is there a question here I should be asking?

LB: [Laughs] Great expectations! The thing is both my parents wanted to be writers, and each of them wrote at least one book. My mom’s was a humor book about being an Army wife. She stowed it away deep in a desk drawer, and, as far as I know, never looked at it again. My dad’s was a novel about his Vietnam experiences — he was stationed there during the war — and he worked on it for something like thirty years, off and on, and then tossed it in a fire. Pretty dramatic, huh? So I was always conscious that I was doing what my parents had wanted to do themselves and conscious, too, that, by succeeding at it, I was in some ways leaving them behind. But kids are supposed to leave their parents behind, right? I would love to eat my kids’ dust.

CH: Spoken like a parent who loves his kids.

I’m curious about a moment in time that strikes me as a pivot point in your creative life, though I’ll let you describe this in your own words. Your first two books are very different than every book that you’ve published since then, at least from where I sit. How would you describe what you were attempting as an author at this nascent point in your career? Then, if you can, walk me through the personal decision to make such a dramatic swing from it to historical fiction. In particular, the dark, brooding, and bloody reinvention of the world of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. Because Mr. Timothy feels like the far side of the creative planet from where you began.

LB: Well, the first two books, long out of print, were drawn very much from my own gay D.C. world. What changed was me deciding — and here’s where the ambition comes in — that I could rise out of the plane of my own life and write about people and places I’d never experienced. Which is to say, I guess, embracing the whole disreputable promise of fiction.

CH: What you just suggested is that you found that writing from your lived experience wasn’t necessarily as exciting to you as the promise of writing fiction very much removed from your life. It’s a complicated, nuanced question, and one I don’t want to get carried away by here, but I do have to ask now: what do you make of the argument that authors shouldn’t write outside their lived experience?

LB: Oh, I think it’s bullshit. And so deeply limiting. I mean, I think some of our lived experience inevitably filters into our work, both consciously and unconsciously — I think all my books are pretty clearly the products of a gay writer — but surely the great joy of doing what we do is imagining our way into other worlds. For me, it’s not “write what you know,” it’s “write what you want to know.”

CH: As you know, I’m a great fan of Mr. Timothy. What was that like for you, adapting, or rather reimagining such a beloved character as Tiny Tim in this novel?

LB: Dickens, as I’ve said, was my favorite writer growing up, and Tiny Tim was my least favorite Dickens character, and the idea that I could pay homage to the first and turn the latter into someone I actually liked was peculiarly energizing. I couldn’t wait to dig in, and I couldn’t wait to avail myself of that Victorian English lexicon and color, to really explore language in a way I’d never felt free to do before. When I glance back at that book now, I think: oh, he’s having fun. And I was. And, at the same time, hoping in a rather naïve way that readers would, too.

CH: Did it scare you at all, the ambition of writing not only culturally and geographically removed from your life in early Aughts D.C., but also temporally?

LB: It did at first because I didn’t know what I was doing — I never do, really — and I was intimidated by the amount of research it would entail. But the research wound up being the easy part. If anything, the challenge was stopping the research — because there’s always more to learn — and just writing the damn thing.

CH: You didn’t stop with Mr. Timothy, of course. You decided to write more of what I personally call “gothic noir”. In fact, that’s how I still pitch Mr. Timothy when I discuss it with producers, as gothic noir or, interchangeably, Victorian noir. It feels like the pivot I just asked about probably set you on a new path, so I’m curious where your head was at once it became clear readers would probably want more of this kind of material from you. Was there any apprehension? And how did this moment in time lead to The Pale Blue Eye?

LB: First of all, thank you for the pitching. Everyone should be pitched by someone like you.

CH: You’re kind, Louis.

LB: Second, there was no apprehension. The decision to pivot came from the marketplace and the publisher. Mr. Timothy got a certain amount of positive attention, so I was encouraged to go back to the same graveyard, and I was glad to go there. I mean, it was better than being told to get lost. Honestly, if Mr. Timothy had flopped, I’m not sure I would have gone on being Mr. Gothic Noir or Mr. Historical, but that’s how it rolled.

CH: Let’s chat for a moment about The Pale Blue Eye adaptation. It was a decade or so in development, which isn’t unheard of, but is probably longer than most adaptations take to get off the ground. Everything takes forever in Hollywood, but this certainly took its time. How often did you think about it during this stretch, and how did you react when you were finally told the film was greenlit?