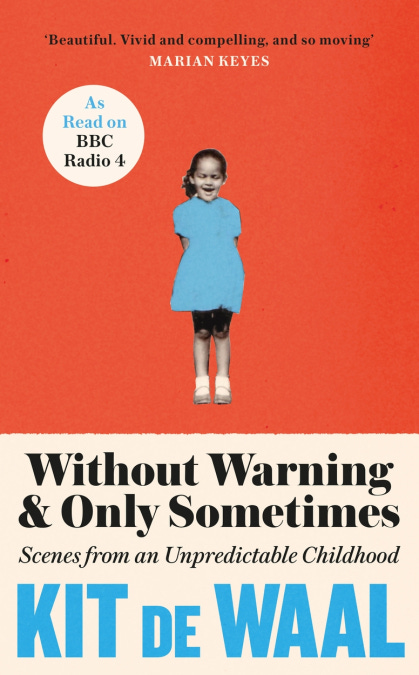

Q&A: Author Kit de Waal on Her Lifelong Love Affair with Classic Film

The acclaimed 'Without Warning & Only Sometimes' writer was indoctrinated into the Church of Cinema at a young age - a passion that continues to influence her work and life today

I couldn’t say what inspired me to pick up Kit de Waal’s memoir Without Warning & Only Sometimes: Scenes from an Unpredictable Childhood — I’m guessing one of the many glowing reviews that accompanied its 2022 release — but I will be forever grateful that I did. Her spectacular prose aside, I was gripped by the story of her childhood in 1960’s Birmingham, U.K. as one of five children born to an Irish mother and Caribbean father. Everything about her identity was mixed, from her race and cultural heritage, to being Irish in England, to growing up in a neighborhood where classes mixed freely but not without challenges. Then came the family’s conversion to Jehovah’s Witnesses, what she calls a cult today, and her escape into drugs and eventual salvation found in reading and writing. Pain and beauty mingle promiscuously through it all, you might say.

If it’s not clear yet, I adored this book, which made it such a thrill when, out of nowhere, Kit followed me on Twitter and we began to regularly tweet back and forth.

She had found me by way of a piece I had written on Top Gun: Maverick, which I assume appealed to her because she’s an obsessive cinephile like me. In particular, Kit lives for classic films, the ones that helped to define her childhood, as you’ll momentarily learn. In her parents’ home, cinema was all-important and its impact on her can be identified in how she writes and creates her own art today. When she agreed to join me for my artist-on-artist interview series — a series especially curious about the intersection between artistic mediums — it was immediately clear this passion for the moving image was going to be the central subject of our Q&A.

What you’re about to read is a conversation about cinema as a religious experience and the storyteller who evolved out of the spiritual escape it provided her (and provides her still). You might want to be ready to take notes because we talk about a lot of amazing films you should be familiar with yourself, if you aren’t already.

COLE HADDON: Let’s start at the beginning - before books and writing were a part of your life. Because you’re rather unique as an author, in that your foundational creative DNA were films and music through various people in your life. Can you tell me what your earliest memory of cinema is?

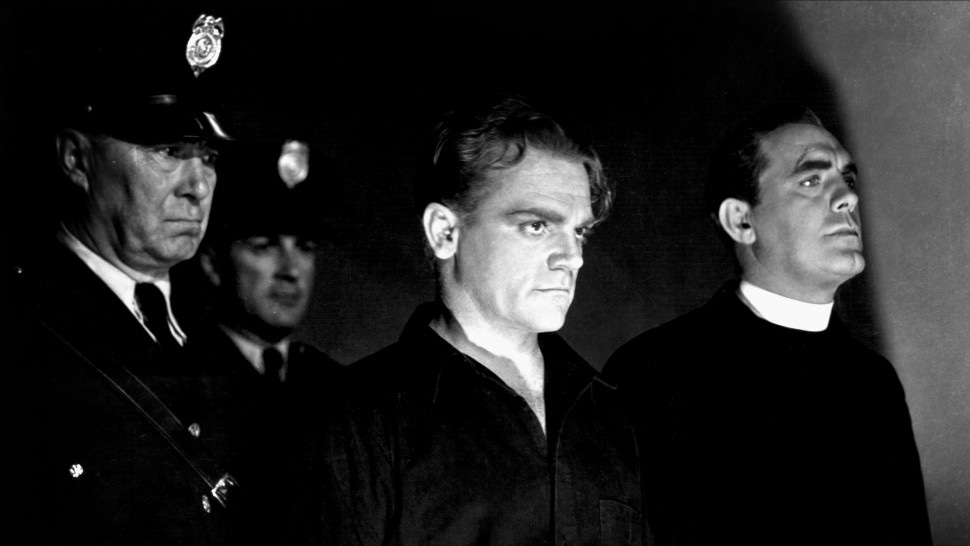

KIT DE WAAL: My earliest memory of cinema would be a black and white film, because we watched hundreds, but the one I’m thinking of particularly is one that starred Jimmy Cagney. My mother was obsessed with him because he looked like my grandfather – very much like him – and, of course, my father was obsessed with film, so if Jimmy Cagney was on, we would call out to one another wherever we were in the house. We would shove in, all of us, the whole family, seven of us wedged into a small sitting room, some on the floor, some on the sofa, my father on his own chair, which was sacrosanct. The curtains would be drawn and the door closed, the MGM Lion would roar and that was that. We were gone. Wherever the film took us, we went there – the huge skies of The Big Country, the sheer cliffs of The Guns of Navarone, the market of Casablanca, and the wide, bare beach of Ryan’s Daughter.

CH: What I find interesting here is how you could be describing going to church. You even used the word “sacrosanct”, which I know was about a chair — my father and grandfather both had their own — but you chose the word as part of a very detailed illustration of what it was like to engage with cinema in your childhood home.

If you think of the Holy Trinity, God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, you could say that…God the Holy Ghost was film, I suppose - a spiritual, intangible, wonderful thing, unreal and hard to explain.

KdW: If you think of the Holy Trinity, God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost, you could say that my father was God in our house, absolutely no doubt about that. The sort of God you don’t question, answer back, or defy. God the Holy Ghost was film, I suppose - a spiritual, intangible, wonderful thing, unreal and hard to explain. God the Son, that one is a mystery, maybe it was all of us, the collective of his children, a tribe.

CH: Did you recreate this experience at all with your children? Did they attend to the Church of the Moving Image like you did?

KdW: I made every attempt to take my children to the Church of Film, but they were never converted. I remember when my son was about eleven, I sat down to watch Jaws with him. “It was really frightening at the time,” I told him. “I dodged school to watch it, it won loads of awards. It’s great.” He was pretty much uninterested until the shark appeared, and then he laughed so hard he nearly passed out. He kept pointing at the screen and saying, “That? You were scared of that?” He took a picture of the screen with his phone and showed his friends.

CH: Christ, this does not give me hope for the future. My youngest son, who is only five, recently groused about being made to watch a black-and-white film, and I all but growled, “We love black-and-white films in this family!”

CH (cont’d): I want to return to James Cagney because he’s certainly an actor I don’t get to discuss enough these days. He’s such a strong man, so working class. There’s a reason why he ended up the face of the early gangster pics and such a hero for struggling ticket-buyers. Do you have a favorite film starring him?

Everyone thought he was a coward, the guards, the boys, the newspapermen, but we knew different. We knew he had done this one righteous thing. This had a profound effect on me.

KdW: There are many films I can think of, such as White Heat and Yankee Doodle Dandy, but the one that had the most impact on me was one where he played a bad guy opposite Pat O’Brien as a priest. The film was called Angels with Dirty Faces and Jimmy Cagney plays a gangster who is revered by some local kids who imitate him. When Jimmy is finally caught and in prison, the priest, his friend, asks Jimmy to go to the electric chair as a coward so that the boys don’t worship him and can go straight. He refuses.

The final scene is a masterpiece. Jimmy Cagney breaks down and begs for mercy. He cries, he fights, he begs, he pleads. Everyone thought he was a coward, the guards, the boys, the newspapermen, but we — we — knew different. We knew he had done this one righteous thing. This had a profound effect on me.

CH: Can you expand on that?

KdW: In that moment, I understood the nature of sacrifice and doing invisible good. I understood that this was the inevitable yet surprising ending that satisfies, and most of all, I understood the circularity of plot, the three acts, the development of character and the hero’s journey. Of course, I couldn’t have articulated one word of all that at the time, but I recall a slight movement inside of me, a shift, a growing up. The world – and storytelling – would never be the same again.

CH: Have you had any other experiences with art — in any medium — remotely as profound as what you just described?

KdW: I’ve had the same experience with music – obviously, who hasn’t? I remember hearing [Miles Davis’s] “Blue in Green” for the first time. My sister put on the LP as I walked into her living room, and I just stared at the disc going round and round while the sax and the piano and the double bass did a number on me. “Oh,” I thought. “I’m here. I’m hearing this thing and this is a moment in my life.”

CH: I honestly think it’s impossible to listen to “Blue in Green” and not have a moment. Is there a book that’s given you an experience like the one you just described or the cinematic ones you talked about?

Having been brought up hungry, I know what it is to look at food and want it and wonder what it tastes like. It’s desire of the very visceral sort, and for [Flaubert] to use it about love made me understand someone I had otherwise nothing in common with.

KdW: When I read Madame Bovary [by Gustave Flaubert]. One particular passage, where a man – a middle-aged doctor in a small village in France in 1890 – is looking through a window at a woman he can’t have, Flaubert says it was like a pauper looking at a banquet, and I felt the words strike my heart. Having been brought up hungry, I know what it is to look at food and want it and wonder what it tastes like. It’s desire of the very visceral sort, and for him to use it about love made me understand someone I had otherwise nothing in common with. I read it once, then again, then again.

It’s not every shift that you register, but then sometimes you are present in the very second, you’re really there in your own body and your own mind and your own time and space and there’s this sort of synchronicity with the universe or the spiritual world – whatever you want to call it. It surely must be the point of being alive, to register those moments and feel the world open up and expand.

CH: You didn’t come to literature until your twenties, so would it be fair to say that cinema is your foundational education in storytelling?

KdW: Yes, film is definitely where I learned about storytelling. There is nothing like inhabiting a film. I’d seen Brief Encounter maybe twice when I was a child and thought it was good. Then I watched it when I was in my twenties, a woman in possession of a couple of broken hearts. “Oh, now I see. Now I understand. Now I’m Celia Johnson, dizzy with desire, deceit, and denial. Now I’m waiting at the train station and pushing the real world behind me so I can be with him, be with him, be with him.” Here is storytelling at its absolute best, with every ingredient of the craft pulled taut, every character so on point and real, and for all its out-of-datedness, all its buttoned-up Englishness, it’s a masterpiece of how to tell a story, what to reveal, when and how to wring impossible tension out of the sound of a key in the door.

CH: It’s a brilliant film, isn’t it? David Lean is primarily remembered for his epics, but Brief Encounter is epic in its own way. There’s a scope to the emotional landscape that startles.

KdW: The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is another masterpiece of storytelling along with One-Eyed Jacks and Notorious. If I ever want to disappear, if I ever want to learn, if I ever want to remind myself of what I’m doing and why, then one of those films will do it every time.

Film, of course, has an advantage over reading in that you can condense a lifetime into ninety minutes.

CH: What impact do you think this has had on how you write fiction and memoir?

KdW: Film, of course, has an advantage over reading in that you can condense a lifetime into ninety minutes. In film, you can paint a visual picture and an audible picture at the same time. And then there are the thousand and one ways you can manipulate and influence the audience without them knowing it. I once did a short course on film noir online with a university in the US, Iowa I think. I signed up thinking, “This will be a piece of piss, but interesting nevertheless. I’ll have to be careful not to run ahead of the other students who might hate me for being so advanced.” First week, it’s pretty general, the iconic films and film stars, the directors and so forth. I’m riding high. Second week, the guy starts in on lighting. “Lighting?” I think.

CH: Uh-oh.

KdW: Oh yeah. He showed us the lighting in about five films, light slanting through shutters, light in a stairwell, light on a desk, overhead lanterns, streetlight, headlights, interrogation light. I was in over my head and out of my depth. Then we did staircases. Yeah, staircases. And on we went. It was absolutely wonderful.

These are things that film can show you invisibly and in literature you have to specify. Both are great mediums, one is not better than the other, in the same way that radio and television are entirely different and accomplish different if complementary things. So, now when I write, I do think “where is the light, where does it come in?” both in a literal and a figurative sense. I paint a scene, and then decide how much of it I can tell, what are the small details that will give the reader the whole picture.

CH: Tell me more about this.

KdW: Stephen King said it was like a diner with a ripped, red leatherette banquette. Do you need any more information to see the diner? No. And why don’t we need any more information, especially for us in the UK where there are no diners? It’s because of film. It’s because our diet of film has shown us that diner and we have chomped it down and it’s there in our guts so that this brief description tells us everything else that we saw in the film – the waitress, the black and white tiled floor, the wide windows and melamine tables, the counter with the chrome stools and the short order cook just out of sight, apple pie under a glass cover, a beige Chevy in the parking lot and one of the customers, just one, with a secret and a broken heart.

I think the reluctance of publishing to acknowledge film is because it’s a very condensed form of what a book is. It’s not worse, but it is condensed.

CH: I don’t recall this King observation — I’m guessing it’s in his On Writing book? — but this is an approach I take with my own fiction, and it’s one that requires the confidence to acknowledge the role cinema plays in popular culture and, consequently, our imaginations today. I mean, the opening chapter of my novel Psalms for the End of the World features the very diner you just described, and I used cinema to fill in all the blanks in people’s imaginations. I had a conversation about this with my own editor recently, about why filmmakers can baldly reference literature and fine art in their work — sometimes even bending form in acknowledgment of them — but the publishing world, especially critics, can feel such disdain toward the encroachment of cinema on all things literary.

KdW: I think the reluctance of publishing to acknowledge film is because it’s a very condensed form of what a book is. It’s not worse, but it is condensed. Also, in publishing and definitely in creative writing, so many students will reference films and scenes when they are discussing literature. A scene in a film is not necessarily a scene in a book. In a scene in a book, there can be flashback, interiority, feelings, history, and great swathes of information with very little action. In a film — unless it’s a French film — something better happen in every scene. Not so in a book.

There is such a lot of overlap and complimentary stuff in film and literature, so, so many books have made brilliant films, but rarely — if ever — has a brilliant film been made into a book. Books can cross the divide where films can’t. Maybe that accounts for the disdain.

CH: We’ve discussed elsewhere how challenging you find it to teach creative writing to students who don’t get any of your film references because you’re talking about Buster Keaton and Cary Grant and their cinematic knowledge goes no further back than Star Wars: A New Hope. Myself, I’d suggest STAR WARS is being generous. In 2007 when I first broke into screenwriting in Hollywood, I regularly met development executives who thought Toy Story was pretty much the birth of cinema. I’m not joking when I say my agents told me to stop referencing Lawrence of Arabia because I was making some execs feel stupid.

I literally said out loud, “What the actual fuck?” ‘Footloose’ is not a goddam classic movie. Neither is ‘An Officer and a Gentlemen’. Neither is ‘Pretty’ fucking ‘Woman’.

KdW: Oh, I am groaning. We all know TCM — Turner Classic Movies — right? Well, one day I turned it on and Footloose was starting. I literally said out loud, “What the actual fuck?” Footloose is not a goddam classic movie. Neither is An Officer and a Gentlemen. Neither is Pretty fucking Woman.

Okay, of course they are classic movies. To my kids, twenty-three and twenty-eight, they are prehistoric, but to me they are so recent as to be laughable examples of filmmaking. Yes, they are good, but they are in imitation of the great classic films and the great classic actors and storytelling tropes and for every Footloose, there is a West Side Story or a Singin' in the Rain. Not the same, I grant you, but please, give me a break with the thirty-year-old classics. Is this snobbery?

CH: Maybe?

KdW: Probably. As a screenwriter, I’ve been in a hundred development meetings or writers’ rooms and when you say Notorious, they think you’re talking about a rapper. When you say [Alfred] Hitchcock, someone will be very pleased with themselves and say, “Oh, yes, Psycho! It wasn’t that scary.” Yeah. Hitchcock is more than Psycho, and it is fucking scary, and that’s not the bloody point I was trying to make. It’s very tiring.

In literature and creative writing, the equivalent are some of the classics or great writers. There are great modern writers, of course, just as there are great filmmakers now. But anyone who wants to know how to tell stories — film or literature — can do no better than study or at least know and appreciate the people who did it first and did it well. Then you can make it your own.

CH: So, I’m curious. We’ve discussed a lot of films and music and books that are, like so much of art, fixed moments in time. Our relationship to them changes as we move away from their origins and our first discovery of them, as life essentially happens to us. But they’re these foundational pieces of us all the same, our DNA in some way. I don’t just mean you. I think this is very true of me, too, which is why I’ve enjoyed the evolution of our social media relationship. What are we to make of the dissonance between the art that informs how we experience the world and the world that’s actually around us? Does it ever leave you feeling dizzy or uneasy or even as if you’re escaping from the anxiety of the here and now for, say, the comforting glow of Cary Grant’s mischievous smile?

KdW: Oh, let me tell you about Cary Grant and Clark Gable and Gary Cooper and Bette Davis and Joan Fontaine and Edward G. Robinson and Robert Donat and Robert Colman and Richard Harris and Michael Horden and I could go on and on and on. There is more comfort in my watching any of those and many others than it is possible to explain.

Here is the contained world, black and white if at all possible, where there are certainties and ways of behavior, where Merle Oberon’s dressing gown has no creases although she’s just got out of bed, where there are hardly any cars on the street, where Burt Lancaster is in charge and has all the answers, where I know what Barbara Stanwyck will say and what Henry Fonda won’t.

I watch those films and those people because I want to know and remember a world that to me was simpler. Whether it really was or I thought it was is immaterial. There were three acts, there was a baddie and at least one goody. There were policemen and love affairs, broken hearts and journeys into darkness, and always at the end, after ninety minutes, I had been somewhere else. I watch those films now for exactly the same reason.

I watch those films and those people because I want to know and remember a world that to me was simpler. Whether it really was or I thought it was is immaterial.

CH: I think that’s exactly why I can’t stop returning to them, even though sometimes it feels like I’m escaping from the real world or, at least, the real problems of today.

KdW: Don’t get me wrong. Nostalgia is bullshit. While Key Largo was being made in the US, there was rampant racism and homophobia. Black people were lynched on front lawns. While Saturday Night Sunday Morning was being filmed in England, children were dying of malnutrition in northern towns and abortion was outlawed. Life is better and we are freer now in many, many ways, but the world felt safer and smaller, analog, containable. Two and two made four.

CH: I feel that.

KdW: I’m flummoxed by the world as it is now. I’m bombarded by information I don’t want, by tragedies I can’t fathom, by crises I can’t help.

CH: You sometimes feel like you’re drowning, and you just need a breath of fresh air.

KdW: I gave a talk recently where I spoke about the need to garden where you stand. Tend the little bit of land around you, literally if you like, but spiritually really. In other words, do the little bit of good to the small area around you, to the people around you, to the local issues that affect you and your community. This is not saying don’t bother with international considerations, with global wrongs, but when you are overwhelmed by the enormity of the problems in the world, it’s sometimes good to go small and go local. Bring your focus back to the garden you stand in and make it beautiful.

For me, film — classic film — is about retreating from the big issues and watching Joan Fontaine fall in love with Orson Welles.

CH: Beautiful, just beautiful answer. Thank you for that. I’m curious, where does your memoir Without Warning & Only Sometimes fit into this conversation? A memoir serves many purposes, of course, amongst them an attempt to contextualize and confront one’s own life. But that also inevitably means returning to periods where things may have made more sense, as dysfunctional as they may have been. You can understand them in hindsight or at least assign meaning to them, whereas you might have trouble understanding what’s happening outside your door right now.

The very act of choosing what life events to write about is an attempt at seeing the narrative, the route through from there to here.

KdW: When I wrote Without Warning & Only Sometimes, I deliberately did not assign meaning to anything. I wanted the reader to experience my bizarre childhood exactly as I experienced it, without any opportunity to contextualize events. Things just happened. As an adult, of course, I can now see the trajectory of my parents’ marriage, or of my own battles with mental health and my determination not to get away from the cult. At the time, however, there seemed to be no plan. And there was no one, not my parents, friends, or teachers, who said ‘This is what life is and this is where you are now.’

I was devoid of advice save for the savage doctrine of Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religion so devoid of joy and understanding that it’s a wonder there’s anyone left in it. I would also say that writing the memoir was, of course, my attempt at making sense of my life and my siblings’ lives. The very act of choosing what life events to write about is an attempt at seeing the narrative, the route through from there to here.

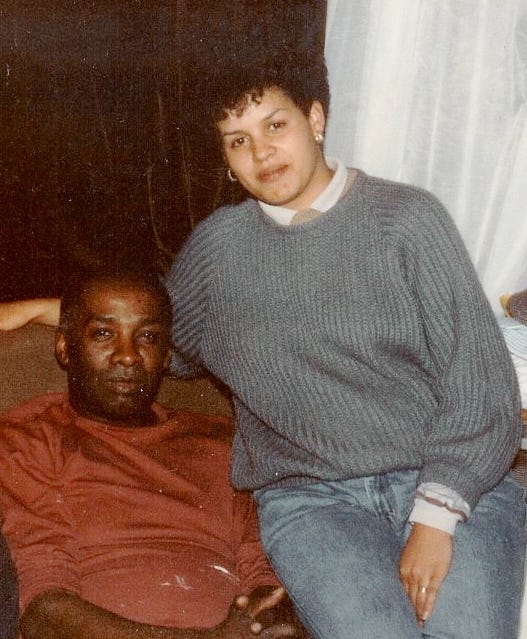

CH: Okay, we’re nearing the end of our conversation. I want to close with two final questions. The first involves your difficult – let’s just say complicated – childhood, which you explore in Without Warning & Only Sometimes and just described, in part, for me. If cinema was the communal language of your household, how do you think your father — God in the Chuch of Film you describe — how would he feel about your life as an author?

KdW: My father would be extremely proud of my accomplishments, but he would be slow to tell me. He would tell his friends at the bus depot and maybe tell my brothers and sisters, but his pride would take the form of questioning me about what I was doing so he could repeat it. He would never say, “You done good, Mandy.” Or, “Well done,” but I would know. We would all know.

[Note: Kit de Waal is a nom de plume; her name is Mandy Theresa O'Loughlin.]

CH: And your final question requires the use of a time machine. You can climb into the DeLorean with any film released after your father’s death, and travel back to any year of your childhood to sit down with your whole family again and watch this piece of the future together. When do you show up, what film do you bring with you, and why?

KdW: Great question. Undoubtedly, I would watch Hell or High Water. I am sitting with my father and I think he’s a fool. I am sitting with my mother; she’s ironing as she watches the telly, disillusioned with her husband and the world. I am with my brother and sisters, eldest one would be seventeen at that time and the youngest would be seven. We have eaten one of my father’s enormous Sunday dinners and we are sitting on top of one another in a fug of warmth and contentment experiencing something that is all but impossible to have now – and that is complete immersion in the moment. There is no pause. There is no rewind. There is no internet. There is no mobile phone. None of us are checking Twitter. No one has to be anywhere else, literally or figuratively.

KdW (cont’d): The film is about fatherhood in a way and the desire of a man to stop the disease of poverty and do one enormous thing, to put himself in jeopardy so that his children do not have his life. And maybe I can see my father differently for all his difficult ways, maybe the film can take some of the cynicism out of me and replace it with understanding and forgiveness.

We will be in the moment, in the wide vistas of Nowheresville, in the bank when it’s being robbed, in the one-meal restaurant and the motel bedroom. And we will be in at the kill, when Jeff Bridges shoots the man who killed his friend. The slap he makes on his leg at the moment he realizes he has avenged his friend — a man he scorns throughout the film — is another one of those moments when you’re inside of him, pleased with the shot, horrified by the act, mourning and celebrating all in one. And my father turns, and looks at us as if to say, “You see that?” Yes, we see it, Dad.

Hell or High Water, a modern Western, is told with great intelligence and emotional truth, no fat whatsoever, no attempt at great explanations. It makes the assumption – rightly – that the audience is with you, the audience is clever, the audience gets it. It’s much like Blue in Green really. The genius is in the unsaid.

I think those of us who watched these films as children are not very successful at passing on our love to our children and, inevitably, there will be fewer and fewer of us as we go on. But that’s life.

CH: Thank you for such a soulful, moving, and, frankly, magnificent conversation, Kit. It’s not every day that I get to discuss James Cagney, Miles Davis, and the existential nightmare of the modern world in the same conversation.

KdW: It’s been a joy to discuss classic film. I’m afraid we are a dying tribe. I think those of us who watched these films as children are not very successful at passing on our love to our children and, inevitably, there will be fewer and fewer of us as we go on. But that’s life. I never want to be one of those people who endlessly feel the world was better in the past. It was only ever different. I look at the tolerance, understanding, and expansiveness of the younger generation, so accepting of difference, so willing to move and flex with what comes along and I applaud them. They are the face of the future, of art, of music, of cinema, and of the many different forms of storytelling including social media. I struggle to embrace AI, but that is undoubtedly the future as well. I hope the next generation can learn how to harness it and use it for the good of the world. Thanks for the discussion, Cole.

You can learn more about Kit de Waal, Without Warning & Only Sometimes, and her other books and writings at her website.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world:

Another great and moving interview. I'm lucky that my parents have shared a love of so many classic films, a fair few of the ones mentioned here, with me.