Welcome to the debut episode of the 5AM Story Talk podcast — a place to talk about stories in all their forms, the craft that goes into them, and the role that art plays in our lives. In the weeks, months, and maybe even years to come, I'm going to be joined by filmmakers, authors, comic book creators, and some other surprise guests to discuss their secret origins, their work and craft, and — and this is what really sets this podcast apart from what else I’m doing here at Substack — a seminal piece of art from their lives that they believe you can learn something from.

Upcoming guests in this audio series include, amongst a line-up already ten names deep, John August (screenwriter, Big Fish), Joe Barton (creator, “Black Doves”), Meg LeFauve (screenwriter, both Inside Outs), Hart Hanson (creator, “Bones”), and Derek Kolstad (screenwriter, the first three John Wicks).

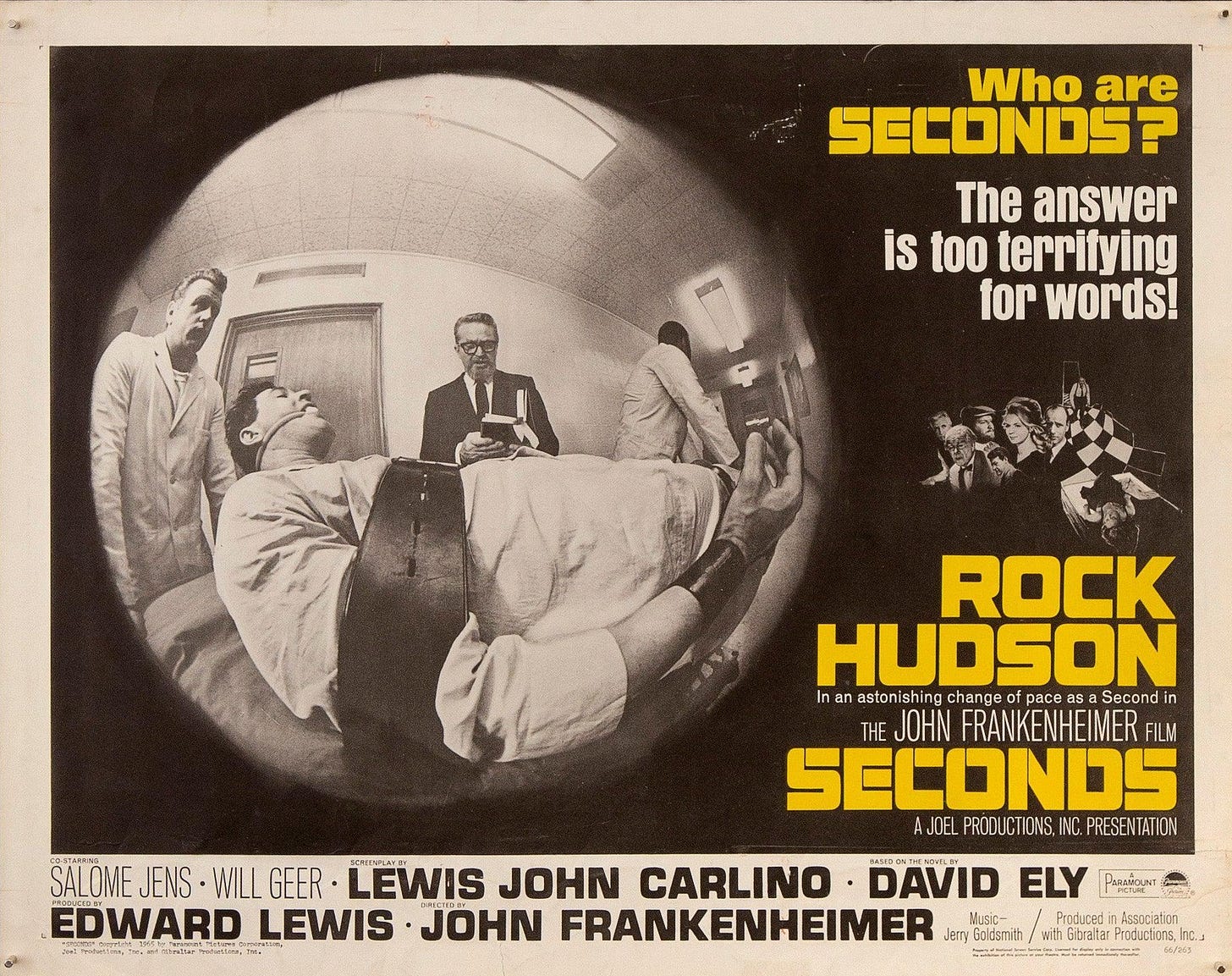

Today, though, I'm joined by Thomas Jane — actor, director, producer, comic book creator, and good friend. You know his work from Boogie Nights (1997), 61* (2001), The Punisher (2004), The Mist (2007), “Hung” (2009), “The Expanse” (2015), and maybe even an Australian TV series I wrote on the second season of recently called “Troppo” (2022). He’s chosen a brilliant film to discuss with me, too — director John Frankenheimer’s psychological (or, as I would say, existential) horror Seconds (1966).

The best way to enjoy this conversation is to click on the podcast play button and just listen to an unabridged version of it in all its glorious, intimate detail. I put a lot of work into it, so I hope it shows.

The text you’ll find below is a transcript edited for length and clarity and presented here for 5AM StoryTalk readers who prefer the written word. Most of it is free, but the paywall will spring up and shout “give me money” at you when we get to Seconds. My apologies for this, but it takes a lot to run this Substack, as you can probably imagine from how much time I spend here.

As for Tom — or TJ, as many know him — he and I met 15 years ago on a general, and our relationship has only deepened over the years since that lunch date. In fact, he's a member of the Three Continent Club, as I call the group of friends who have visited me on every continent I've lived on. I asked him to be my first guest in this new podcast series because, well, I knew whatever we'd talk about, it would be interesting. We share a mutual love for genre, for having trouble with conventional approaches to just about anything, and talking about art.

I also thought it would be a great idea to mix up my typical guest list with someone primarily known as an actor. I'm always trying to give you new perspectives on art, right? I want us to always look at art from new angles, I mean. And for those of you who hope to become screenwriters, or maybe even already are, getting into an actor's head to better understand how they come at a story, how they emotionally relate to it, maybe this will be of some use to you.

But mostly, I just wanted to hang out and talk with my friend about films.

Specifically, we’ll be digging into Frankenheimer’s Seconds, as I said. It was written by Lewis John Carlino, based on the 1963 novel by David Ely, and stars Rock Hudson. It’s about an aging man who's given a chance to start over in — let's call it for now — a new, much younger body. I'd pitch it to you as a Charlie Kaufman-esque horror film.

Tom leads us through a deep dive into the film's anxiety-inducing first act. I can promise you're going to learn so much about screenwriting and filmmaking from him.

If you enjoy this conversation, hit the share button and spread it around Substack and the rest of the internet if you’re so inclined. And if you're not already a paid subscriber to 5AM Story Talk, you can upgrade right now to listen to (or read) us break down Seconds just for you.

Now, without further ado, let me introduce you to my friend, Thomas Jane…

COLE HADDON: Thanks so much for being here, Tom, and having this, uh, this chat with me. I think we've known each other now,

THOMAS JANE: Don't say it.

CH: Yeah, more than a decade.

TJ: At least fifteen years.

CH: I can't even remember the name of the restaurant we met at, but it was on Melrose.

TJ: Well, you sent me a script. I don't even know how that happened, but either before or after we met, I can't remember. And it was Quatermain, which I just fell in love with. Right up my alley because it had, it had heart. I'm always looking for heart.

CH: I appreciate that. So, I like to start with weird pop existentialism questions as I call them. So, I’d love to ask: why does art matter to you? Why aren't you doing anything else?

TJ: Starting in the shallow end of the pool, eh? [Laughs] Well, you have to ask, what is art? And to answer that, you have to say, what is it that separates humanity from the animal? And what it is, to boil it down – as far as I can tell, or at least smarter people than me say – it's symbolism. Symbol. Symbol separates man from beast. It allows us to communicate over great distances, both temporal and geographic, so we can pass our ideas on to others who build on those ideas. And that's how, through the generations, we grow wise. It's through symbol. Language is the obvious example, but art, painting, sculpture, and every other kind of sort of symbolic art that you can think of.

We who do art are kind of engaging in, in sort of like the purest sort of human endeavor that one can do. So, that's a great privilege. It's also a birthright for every human being on the planet. It is, in fact, what we do as human beings. It separates us. It allows us to understand the world and pass that understanding, whether right or wrong, onto others who then grow and somehow evolve. So, it's a privilege to be able to do that.

Why I'm an artist, I have no idea. It's just sort of like where my head went since I was since I was a wee lad. And then you start, you know, choosing that journey. You just start down the path, you gravitate toward what turns you on and usually end up imitating it in some way or trying to contribute to it. And so, I feel grateful that I've been able to do that in whatever little way that I've been able to do. It's an obsession, you know? It's something that I wake up with and dream about, and then fall asleep and dream some more. It just, it never ends. It has no on or off button. It just is.

CH: So, another light question, what's the scariest moment you've experienced as an artist? And I don't necessarily mean a threat to your life. It could be creatively or emotionally.

TJ: Well, I don't know. I mean, what's scary, there's a couple different sort of like ways to be afraid or freak yourself out. One of them is the fear of failure. And the other one is the fear of, breaking through a kind of level of expression that you're, that I'm afraid of because it challenges, parts of myself that I'm not comfortable with or that I'm scared of. When I was younger, it was anger. I was pretty angry young man, and I was afraid of my anger of sort of getting out of control when you're a young actor working with emotion, because that's what we do. You know, we work with the paintbrush of emotion. Well, you're confronting the emotions that you have, and if you're, you know, a good actor, you're tapping into real emotions. When I was a young actor … I wanted the material that I could express myself with. It was all about me and that character, and I didn't really worry about the rest of the story that was being told. There's a kind of myopicness to that that I think serves an actor, you know? Don't worry about the big picture, focus on this moment, what your character's here to do, and what you're here to say. And that works. But as I got older, I started getting more into story and the bigger picture. that's kind of what turns me on now. Learning about story has become sort of something that's become now my frequent obsession, which is a whole other ball of wax.

CH: We're going to dive into all that one more question before I get to it, what's the worst advice you've received from someone in the industry that hurt your career or creative ambitions?

TJ: Oh, I don't know. I've turned down parts that I wish I hadn’t. And I've gotten advice as a young guy to turn stuff down. An agent once told me, “You'll never regret parts you turned down.” And I found that to be really untrue.

CH: Do you likewise regret parts you said yes to?

TJ: Oh, sure. I mean, some. Not many. I regret how they turned out, you know. Most of the scripts that I've been really passionate about, because they were really good scripts, didn't turn out to be such good movies. And that's just the way it goes. That's always disappointing. You go in knowing that your heart's going to be broken in a hundred different ways, and you do it anyway.

CH: Is that how you feel? Do you, do you steel yourself before every production? Tell yourself that this is all going to go wrong so that you can be pleasantly surprised when it doesn't?

TJ: No, I focus on doing it right. I always give it the benefit of the doubt. I always say this is going to be the greatest movie ever made. And then try to fight the battles that would make it as good as it could be, and then the chips fall where they land. But I don't think you can go into something with – well you can – but I don't think it serves you to go into something sort of like thinking that it'll fail. I think you have to go in with your heart open, you know, like a like a love relationship. I've been in love a few times, and they've always ended in heartbreak. But when you fall in love, you're not thinking, “You know, this is all going to end in tears.” At least not at first.

CH: So, looking back I became aware of you with Boogie Nights, and I feel like, was a turning point for you. You delivered this amazing performance and all of a sudden, I was seeing you in two or three things a year after that. Was it a turning point for you?

TJ: Yeah, Boogie Nights was the movie I did where I became a working actor and I didn't have to have another job. That was great. I always would quit whatever job I was doing whenever I got a part, even if it was a one day part in a commercial, and I would take off my apron and throw it on the floor and walk out. Then, a month later I'd be back at some other job, sweeping the floors of some other restaurant.

CH: The really iconic part of the performance, you're there opposite Alfred Molina and Mark Wahlberg. These aren't lightweights, but it's always felt to me, at least – and I think a lot of people – that you stole that scene. What was it like being so new in the business and being dropped into that?

TJ: You had a benefit of having a director who understood performance and was really in love with his actors, and really knew how to get the best out of them – or at least in the cut. He did a lot of takes, so he had a lot to choose from, but I, he chose wisely. So, I guess I didn't realize how spoiled I was at that time. It's fascinating how few people know how to put a movie together. You know, it's the intersection between art and work. I think that the business side of things means that they have a hell of a lot of stuff that needs to get made, and I think a lot of people sort of fall into the kind of workmanship of the craft instead of the passion or the art of the craft, you know?

CH: After Boogie Nights, you seem to vacillate pretty dramatically back and forth between smaller indie films and more commercial films. Was there a tension within yourself about what kind of actor you were going to be, what kind of career you were going to have, or were they just parts you took and hoped for the best from?

TJ: A little bit of both. You tried to take the good part, the parts that I felt that I could give something of myself to. That I could, you know, score in emotionally. I still do that. I try to pick roles that I feel like I have something to offer to. It didn't matter to me if it came from a studio picture or an independent film, although my heart has always been independent. When I was a teenager, I was a punk rock lover. I loved the punk rock ethos. Those guys were cutting their own records and selling them on at their own shows, and they didn't have a record label. They made their own art. They made their own music, like Discord out of Washington, DC, which was a great inspiration for me. But unfortunately movies are way more expensive than some recording equipment and some instruments in a basement. That's a lot harder to do, but I've always gravitated to the indie stuff, and I have a love/hate relationship with the studio stuff.

CH: That punk the ethos isn't necessarily a good fit for the studio system.

TJ: I've alienated myself from the studio system without even trying. I just didn't want to play along. I dropped out of high school in the 10th grade. I never got along with my peers. You know, it's just part of my makeup. My, my mother was a very private person, isolated. Never had any friends and nobody ever came over. I wasn't integrated. I started school late. So, when I got there, I was an outsider. All the other kids knew each other. I didn't, and it just kind of stuck with me throughout my life. I'm still that way today. And, and it's been a detriment to me, for sure. I don't go to the [Hollywood] parties. I mean, I went to a couple of parties, but I would never stay. It just didn't turn me on, and it's probably out of some kind of fear in myself. I've got a innate disdain for humanity on one hand, and then, on the other hand, I've got a deep fascination and love for humanity – which keeps me sort of doing what I'm doing and wanting to do what I do.

CH: Let’s talk about genre. I know it's such a passion for you. As long as I've known you, we’ve shared that in common from, from film noir to science fiction, comic books, all of it. Was it important to you as a kid, too?

TJ: Oh, yeah. No, again, like early formative experiences, my dad was a movie guy. My parents didn't have money for a babysitter, so they would drag me and my sister to movies, and it didn't matter what they were, [even if] they were R-rated. My dad had an act for hunting down movies that he thought would be cool – [like B movies] – and he still does. My experience with Hollywood was the VHS. My dad brought home that big clunky VHS machine in the early ’80s. We started going to the video store, and that's how I watched 2001, the James Bond stuff, Clockwork Orange. But my movie experience was very sort of like surface level.The deepest I got was one of my buddies in high school got ahold of a copy of Eraserhead. And so we'd maybe smoke a little and watch Eraserhead, and that kind of blew my mind.

TJ: But I also had a big comic book fetish and discovered underground comics. Again with the punk rock ethos of the underground comic, where you print your own books, 2,000 copies, and send them to record stores and comic shops around San Francisco. They became precious, even in the, in the ’80s. Any comic book shop I'd walk into, I'd be like, “Where's your underground section?”

TJ: So that was a big part of what turned me on, you know, these sort of like these personal transgressive stories that weren't suitable for publication.

CH: Staying with genre somewhat – Stephen King films. You've done three and I know you're working on a fourth at this point. I think you've also starred in one of the best King adaptations, that being The Mist – at least in my opinion. Have you worked out what makes a good King adaptation? Especially as you develop your own?

TJ: Yeah, I have. King has a point of view, it's a tone and it's suburban, it's natural, it's intelligent and it's always surprising. It's never horror for the sake of horror. It's always a human with real human beings, and that's what makes it terrifying. King is of the great literature artists of all time, and he'll be recognized as that. Right now, we still kind of see Stephen King is a paperback novelist who writes genre stuff. That's not my estimation of King at all. I think he's deeply literary, and his exploration of the human soul is deep. I wouldn't put him in the same boat as Dostoevsky, but it's a similar branch of the library, you know – dealing with real human truth. What makes a good King adaptation is to capture that. Where people fail is by treating it like a genre. You don't have to worry about that part. What you have to focus on is capturing real human beings in real situations and with a certain intelligence.That's why [the Frank] Darabont stuff is probably some of the best King – because he understands that tone and he was able to recreate it on film.

CH: I appreciate your point that approaching King as genre is the mistake. I've worked with many producers even studio executives who don't respect genre in the right way. They don't understand it's just a label, that the story itself deserves the same respect you would give to what we’d call drama, and once you begin to treat it as anything other than straight drama that happens to just coincidentally have some extraordinary details, you diminish it in some way and it stops resonating. That's when you start slipping into camp or you wonder, “Why isn't it resonating with audiences? Why doesn't it feel real?”

TJ: It's the common mistake with genre, but that's why I like your work so much, because you certainly respect the reality behind the characters, the truth of the situation, and for any movie to be good – or any story, or any piece of work to be good – it has to be a reflection of some sort of reality.

CH: Not long after The Mist, you started publishing comic books, which is right around the time that I, I met you. You directed your first film, Dark Country, which is this wonderful and weird, creepy little film in “The Twilight Zone” vein, and you've gone on to direct more TV – including an episode of mine on, on “Troppo”, which was a huge honor. You're producing a lot now, too. This isn’t really a question, but I want to observe that I’ve always been amazed by how it seems like you're just out there doing your own thing. Is that related to what you were talking about, the punk ethos? “Fuck it, I'm just going to do my own thing?”

TJ: Absolutely. I mean, if I wasn't doing that, I'd be going bonkers. It's just what's always turned me on, and it goes back to the love for underground comics and punk rock music. I wish I could have a punk rock film studio and make punk rock movies, you know, and maybe I'll get to do that.

The stuff I like is always a little left of center so getting those things off the ground has always been a little tougher. I wish I paid a little more attention to the movie star thing when I was younger so that I had a little more box office cachet these days, so that I could make some of the movies that I want to make. Because that's always a part of it, but I'm also amenable to stepping aside and letting other people star in the damn thing because directing and producing is really what kind of gets me out of bed these days. I've really grown fond of learning about story and learning how to craft the experiences that I had as a kid – [the experiences] that really galvanized me. Saved my life in a lot of ways. I had a tough home life and, movies, music, these things, they mean a lot to young people. They can really be a lifeline for a lot of people, for a lot of different reasons. That keeps me going, trying to create something that the kids will, you know, not only get a kick out, [but will also] be something of a lifeline. It’s really important, and I really think that's why I do what I do. I'm trying to save myself for when I was a, you know, a young man and a teenager. I think that's a lot of a lot of the motivation…save myself.

CH: It's a lovely thought to sort of go back in time, metaphorically, but just do for others what you didn't have or, you know, the right movies did for you. In some way, it's you're continuing the tradition of saving kids with weird shit.

TJ: Exactly. Yes. And if I don't do it, who the hell else is?

Most of the stuff that made the biggest difference to me when I was a kid was not mainstream. That still exists, but it's hard to find. So, I like doing the independent stuff. I try to create stuff that has a chance of being different. Most of it's not very good, but sometimes you land on something. You feel like you've made a contribution, that's what matters. Finding ways to be creatively productive in ways that are meaningful, I think, is is key.

CH: Well, thank you for the conversation so far.

TJ: I can't wait to talk about seconds, man. It's one of, it's a cult movie and one of my favorites.

CH: It's so good.

As for you at home who took the time to listen to — or read — this conversation, thank you for tuning in, as we used to say once upon a time. If you're a free subscriber to 5AM Story Talk, the paywall is about to jump up and shout, give me money if you want to hear more. Sorry about that, but I've done my best to keep as much of this free for you as possible, despite the immense amount of work these things can take.

Subscriptions cost $6 US a month or $60 a year, and for that, you get access to the rest of this episode, dozens and dozens of similarly intimate, hopefully insightful conversations with other artists like Thomas Jane, monthly chats where you can directly ask me anything about the arts, and a whole lot more.

If you tap the become a paid subscriber button right now, you're going to be able to listen to more than 30 more minutes of my conversation with Tom as we break down in some pretty incredible detail the first act of John Frankenheimer's brilliant 1966 film, Seconds. I hope to see you there.