How to Survive Your Biggest Mistakes as an Artist

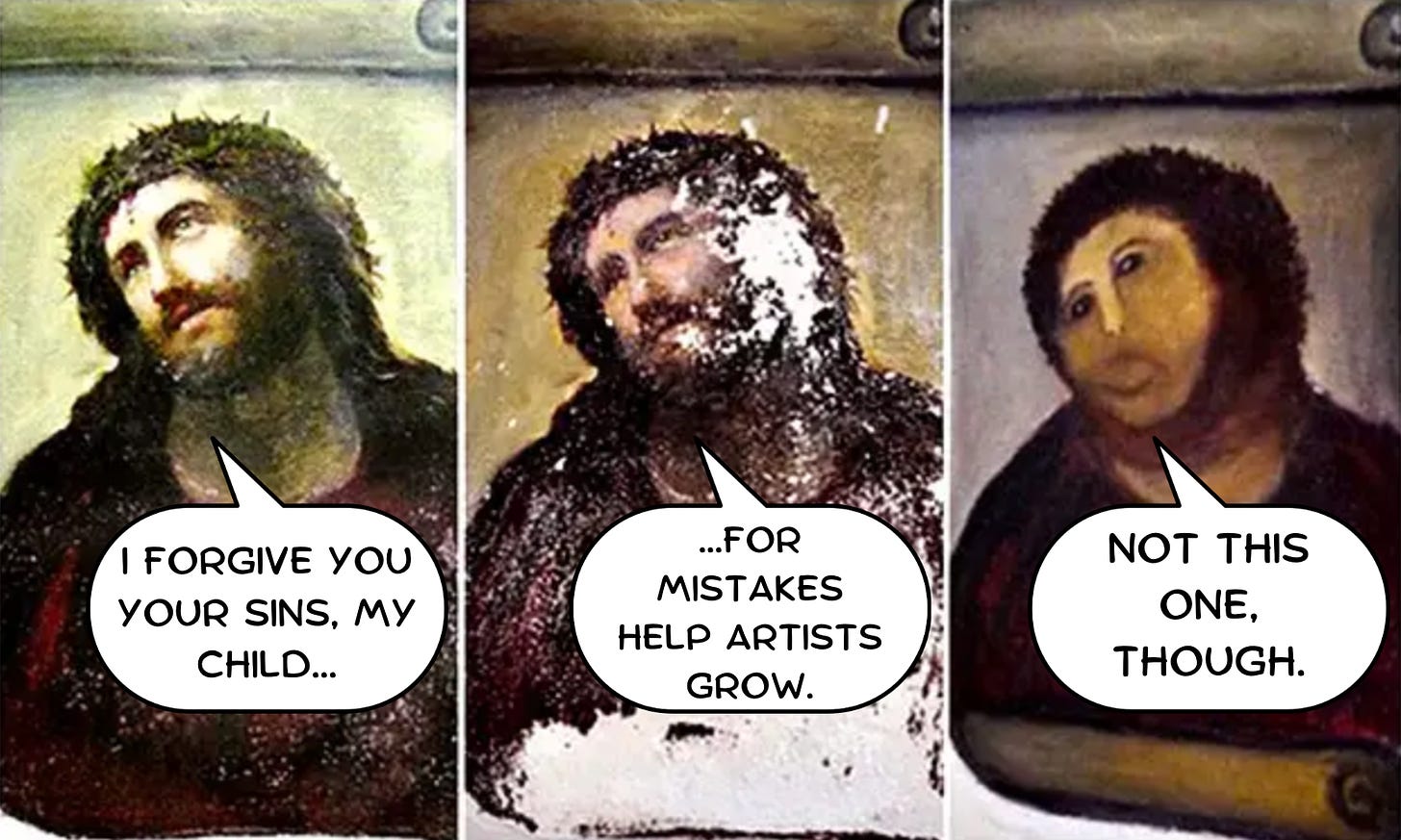

25 filmmakers, authors, and comic book writers from around the globe discuss what they learned from their worst professional and creative missteps

“The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory. Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error.” – William Faulkner

If you’re a regular reader of this arts Substack, then you know I have made a lot of mistakes in my fifteen years as a professional artist. While most of these were in my career as a screenwriter, there are also many I’ve made as a comic book writer and, more recently, novelist. Some were in response to terrible things that were being done to me — moments in time in which I could’ve gone right or left rather than hurled a grenade and ducked for cover — but there are also some which were just made out of good ole fashioned ignorance for the industries I was working in. I’ve tried to be as forthcoming as possible with you about these experiences in the hope that they might help you wherever you are on your own creative journeys.

But a strange thing happened as I discussed these mistakes here on 5AM StoryTalk. Other professional artists began to reach out to me to tell me about their own professional traumas. Sort of the artists’ equivalent of swapping war stories. In interrogating what happened to them, I realized we are almost all fuck-ups in some way or another. Many of us get it wrong as often as we get it right for a lot of our careers. Over time, that balance begins to shift toward the latter, of course. That’s because of the wisdom gleaned from all that mistake-making in some form or another.

So, this April, I decided to dig even deeper into this subject with the help of twenty-five friends old and new - call them a chorus of professional filmmakers, novelists, and comic book writers/artists. This is the specific question I posed to them:

Talk to me about mistakes. For example, what’s the biggest mistake you’ve made as an artist and what did it teach you?

Below, you will find the responses I received. In addition to the variety of mediums these artists work in, they represent a diverse range of voices and cultural backgrounds from across the globe - including the United States, United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand. Hopefully, their perspectives and experiences will be of some help to you wherever you are on your creative journey.

ANGELO PIZZO (screenwriter/co-producer, RUDY)

Our first two films (Hoosiers and Rudy), despite constant worries, second guessing, doubts, and fears, turned out to be successes. Then, a third opportunity presented itself that appeared to be a sure thing: bigger budget, larger scope, great story, the whole enticing package. We figured we couldn’t lose.

But in retrospect, we were blind to the warning signs flashing at every turn. We were confident, to the point of being borderline arrogant, that we possessed the magic formula of how to do these kinds of films. Things began going downhill early, but we still thought we could pull it off because of past experiences. However, we had found ourselves in a hole, and the more we struggled to climb out, the bigger the hole became. A friend once told us, “You guys went to the Bank of Karma and found out that after your first two films, your accounts had been overdrawn."

This business can humble a person totally and swiftly. I was shaken for years after, and have not had a twitch of cockiness since. Paradoxically, I look back and value that disaster, as I truly did learn more from that time than I did from any of my successes before or after.

Angelo is a U.S.-based filmmaker.

JO CALLAGHAN (author, IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE)

After writing five books that failed to get published, I finally decided to give up writing. But then my husband got sick with lung cancer, and I began to write a blog about our experience as a way of processing the terrible lurches between hope and despair. I gave the blogs very little thought, and would literally bash them out early on a Saturday or Sunday morning to get all the thoughts out of my head and onto the page. Yet the feedback was incredible. People were so supportive and kind about Steve and our children, but also, bizarrely, I received lots of compliments about my writing. I couldn't understand it. I wasn't even trying - I was just writing how I felt.

But of course, that was why it resonated with people. Belatedly, I realized that I had written those five unpublished books in my “telephone voice” - I was trying to sound like a “writer”. But it was only when I wrote from the heart without fear or filter that my words connected with people. When my husband died, I carried on writing in this way. In the Blink of an Eye was partly based upon my own experience of being a widow returning to work, and I wrote it not to get published, but as a way to stay sane during those raw first months of grief. So as an artist, the lesson I learned is to heed Hilary Mantel's advice to “write with blood”. But as a human being, I worry that the biggest mistake I made was all the time I wasted writing unpublished books, rather than spending that time with my late husband or now grown children. I think that is a dilemma that all artists face, and in all honesty I don't know what the answer is.

Jo is a U.K.-based author. Her second novel, Leave No Trace, is out now.

DARA RESNIK (creator/showrunner, “HOME BEFORE DARK”)

I promoted two people on a show who weren’t ready to be promoted. One was a young producer who I advocated to bring on as a lead on the project because I felt he had truly championed the piece from the beginning and I thought he was ready to handle the responsibility. The other was a young creator who I advocated should be my equal partner even though my original contract said I was the final decision maker. Neither had made a television show before.

As the show progressed, it became clear neither appreciated the art of community creation that a great set begets. Neither understood that the magical alchemy that makes a a show truly work is trust, support, and community — and creating that is a talent in and of itself. In the end, both jockeyed for power. And they were each out for themselves and not the collective. The mistake I’ve made more than once — and I hope this is the last time — is assuming other people in this business are playing the same game I’m playing, with the same rules. Andm unfortunately, too many new creators don’t understand or appreciate the process enough to play it as anything more complex than a zero sum game. If I was ever in a similar situation again, I’d make sure to get through an entire season of TV first, gauge emotional maturity and intelligence, and then decide whether someone was ready to be promoted.

Leadership in television isn’t just the ability to make good creative choices — it’s also the ability to create a safe creative bubble where all the artists involved feel like they can take risks and big swings.

Dara is a U.S.-based screenwriter. You can read my recent artist-on-artist conversation with her here.

TOM HOLLAND (screenwriter/director, CHILD’S PLAY (1988))

Saying okay when the United Artists lawyer on CHILD’S PLAY wanted to make my bonus on sequels dependent on my getting “co-story” credit. Not just co-screenplay credit, but co-story credit. Based on my previous experience as a writer, I had won every arbitration, so I assumed it would happen again. After all, I had created Charles Lee Ray [in the script], the Lakeshore Strangler, and the concept of putting a serial murderer into a doll which was then given to an innocent seven-year-old. What I didn’t realize was that the WGA standards were different for a writer seeking co-story credit and a director-writer seeking the same. They were much more stringent for a director as the WGA tried to protect helpless writers from marauding directors who unfairly sought screenplay credit.

Lesson: Put on your lawyer hat and read the standards in any situation in which credits may be arbitrated, which is basically all in which there is more than one writer and especially if it’s a writer-director. Don’t depend on your lawyer or agent. Read the rules of the guilds involved in such situations, including the DGA’s.

The only one who will protect you is yourself. Nobody cares about your money as much as you.

Tom is a U.S.-based filmmaker and author. His latest book, Oh Mother, What Have you Done? The Making of Psycho II, is out now.

KAYLA ALPERT (screenwriter/executive producer, “WEDNESDAY”)

I’ve made so many mistakes, where do I begin? While I can’t narrow it down to one specific moment or episode — I could but that’s just too painful — there is one recurring theme which is…self-advocacy! I’ve written and produced numerous pilots, movies, worked in writers’ rooms and on sets - and been represented by some of the biggest and best agents and managers in the business. I’m a force in a writers’ room and I am known for having a strong vision for my original work.

And yet…I don’t think I’ve ever fully advocated for myself. Part of that is the nature of the business as a woman - where we’ve often been labeled “difficult” if we make waves or push back against a script note. I’ve never seen a male creator hesitate to speak out, call a network president directly, or take his rep to task for failing to secure a good deal.

And yet…I can think of countless times where I’ve fallen into the people-pleasing trap of “If I just behave nicely and leave it to my agents, managers, producers, executives, etcetera, then everything will work out…” But the truth is, nobody will advocate for your work harder or more passionately than you can. And if that means stepping outside of your comfort zone, pushing your reps to ask for more money or more time, or taking a stand against a shitty idea then go for it. What’s the worse that can happen? Well…I don’t know. I’m still working on it.

Kayla is a U.S.-based screenwriter.

KATIE LOVEJOY (screenwriter, LOVE AT FIRST SIGHT)

Oh man, what mistakes haven't I made? I think my biggest one is that I spent a lot of years writing things because I could, not because I should. I got my first professional writing job when I was twenty-three, so I came of age in the business, and while that was wonderful in so many ways, the challenge was I didn’t really know who I was and what stories I wanted — or perhaps more aptly, needed — to tell, so I wrote basically anything I could get paid for. Financially, that was not a mistake, but creatively, I ended up feeling very lost. I didn’t have an artistic North Star. I just wandered around, bumping into different stories and genres and opportunities and saying, “I could write that!” It wasn’t until I stopped to ask myself, “Should I write that? Is this a story I want to tell?” that I started getting things made.

My first produced credit was a pilot called “Miranda’s Rights” for NBC — it was a legal soap that basically asked the question, “what if Monica Lewinsky tried to get a job as a lawyer?” — and while I had neither been a lawyer nor embroiled in a sex scandal, I wanted to tell a story about overcoming shame and forgiving yourself. I was twenty-seven at the time and finally examining the crushing perfectionism that had driven me my whole life — and made me miserable — so writing about self-forgiveness felt vital to me. And sure enough, that vitality showed up on the page, and I got the thing made. (But not to series, that’s a story for another time.) I’ve learned over time that I have some thematic favorites — for example, characters who deal with grief through humor — but my artistic North Star does evolve as I grow. Now I know to stop and check in with it before embarking on a new writing journey.

Katie is a U.S.-based screenwriter and one of the survivors of the complete and utter shit-show known as “Dracula”.

DEBORAH SPERA (author, CALL YOUR DAUGHTER HOME)

My biggest mistake was not writing sooner. As a producer, I hid behind working with other writers on their material for thirty-five years. That’s a long time to be a midwife. I was scared. Scared I’d suck, scared I’d make a fool of myself, scared I was all talk. I love story more than anything. That’s how I survived hiding from myself producing movies and television for thirty-five years. I was fifty-seven when a literary agent called and told me the short stories I’d written were novels in disguise. She wanted me to start with the first one — there were five — and make it a book. Oh, and, she said, “I want to represent you.” I was stunned. These stories were meant to feed my creative curiosity as I recovered from a softball injury and subsequent surgery. I was laid out flat and all I could think about was writing these five short stories about how five generations of women rise from abject poverty and dependency in a patriarchal society to prosperity and autonomy. And each generation would be set against different backdrops of time. So, I wrote five stories in the safety of my bed. And now here I was in my late fifties when this wonderful agent called, willing to invest in a skill I wasn’t sure I had. I called the first person that came to mind, Meg Lefauve. She’d done what I was being asked to do. Give up one identity – producer - for the true identity of artist. I was hysterical, I’m sure she thought somebody died. She calmly and gently explained to me what a shadow artist is, and that I’d been one for a long time, but now that was over. I had to face myself, my true self. My husband told me to carve out an hour a day and write badly, as badly as I could. And that’s what I did. Within a year Call Your Daughter Home was sold in auction and has to date sold over 300,000 copies. The entire journey was the biggest surprise of my life and the most gratifying moment of my career. A pinnacle. So yeah, my mistake was not believing in myself sooner. I missed a lot by doing that. All the self-doubt and fear I carried, and still carry, can make me sad. But then I tell myself, gentle, gentle, gentle, nothing grows in that space. I may have been late to the party, but I got to the kind of party I belong to, despite my age.

Deb is a U.S.-based author, screenwriter, and producer. Her debut novel, Call Your Daughter Home, is out now.