How Hollywood CEOs Broke the Economics of the Film/TV Industry

Guest contributor screenwriter Rob Forman weighs in on the choices that 'disrupted' and wrecked a business model that had been profitable for more than a century

Today’s edition of 5AM StoryTalk features a guest contributor whom I’ve invited to discuss how Hollywood’s legacy studio and streamer CEOs have upended the economics of the entertainment business: television, feature, and video game writer Rob Forman (“PARTY & PREY” and the upcoming SPIDER-MAN 2 video game).

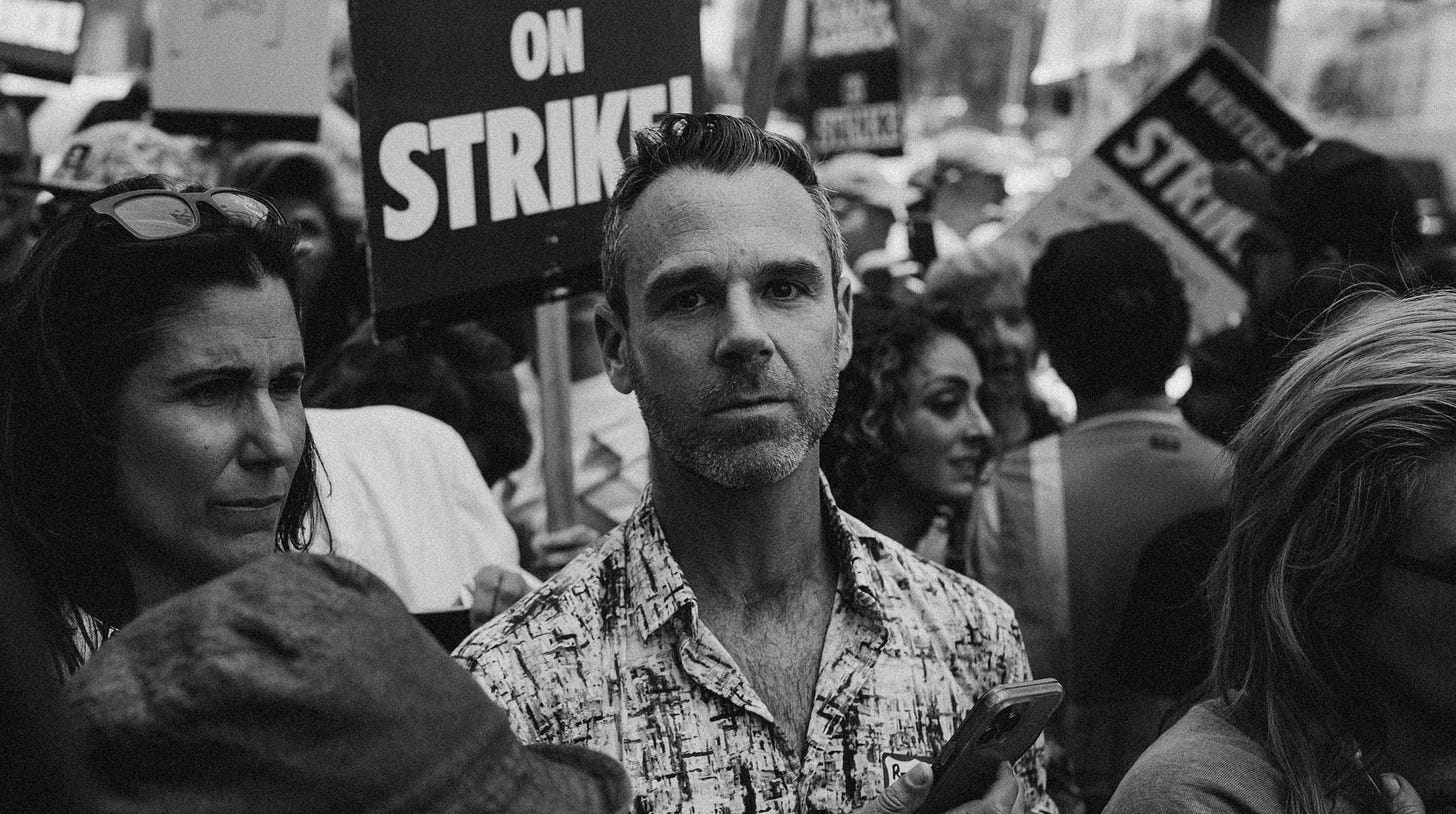

Rob, a member of the Writers Guild of America West since 2012, has served his union during that time as vice and co-chair of the LGBTQ+ Writers Committee and as a show captain, contract captain, strike captain, and, most recently, as a lot coordinator at Universal in support of the current WGA strike. He’s currently running for its Board of Directors.

In the fall of 2004, I was a junior pursuing an undergraduate business degree at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania while also doing a minor in English and Cinema Studies. I took a course called “The Hollywood Film Industry”, in which we studied the history of the old studio system, independent film, how distributors get paid, and even an upstart company called Netflix that was challenging video rental stores by mailing DVDs to subscribers.

During the semester, the professor who taught the college’s introductory Film Theory course, the late John Katz, delivered a guest lecture. He opened by drawing a simple line chart on the chalkboard to show a basic supply-and-demand business model. Then he drew two vertical lines with a squiggle, stepped back, and said that this was how the Hollywood studio system operated and what it cared about.

Professor Katz had drawn a dollar sign.

Because entertainment is a business.

I was viscerally reminded of this when The New York Times published an article on July 15th titled “In Hollywood, the Strikes Are Just Part of the Problem”.

This article details the various threats and disruptions Hollywood studios face, from massive tech companies becoming dominant players in the industry, to box office ticket sales not yet recovering from the pandemic, to decline of the traditional network television and linear cable television models in favor of vertically integrated streaming services, to — yes — the labor disputes of the current WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes.

Existential hand-wringing has always been part of Hollywood’s personality. But the crisis in which the entertainment capital now finds itself is different.

Instead of one unwelcome disruption to face — the VCR boom of the 1980s, for instance — or even overlapping ones (streaming, the pandemic), the movie and television business is being buffeted on a dizzying number of fronts. And no one seems to have any solutions.

The article’s main point is that once the strikes end, the underlying business challenges will remain.

But I felt there was something missing in the story: the agency of the CEOs of the companies that comprise the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

People make choices.

Ultimately, this is the most basic tenet of storytelling.

In other words: industry-wide business models do not change on their own. If they did, it would only be because AI has replaced the very CEOs who seem reluctant to put guardrails on the technology’s use. Disruptions happen, trends change, and people decide how to respond to them. The CEOs of the companies that make up the AMPTP made choices and changed the business model.

We should, then, examine the choices these CEOs have made over the last decade-plus as the entertainment business shifted to the streaming model. No writer or actor insisted on these courses of action…but nearly every Hollywood legacy studio and streamer CEO chose this path.

The Death of the Mid-Level Budget Film

Mid-level budget films, which don’t need to generate north of $1B at the global box office just to cover production and marketing costs, used to be core profit drivers. A lower budget means a lower bar to achieve profitability and that back-end revenue streams such as licensing and home video were often pure profit. Yet, outside the resilient horror genre, these films have all but disappeared from theaters. They are now largely confined to streamers, where there is generally no back-end because they exist only within a walled garden of content.

This is among the reasons writers and actors are demanding data transparency and a streaming residual tied to performance: to once again share in the success of a project when it is successful. If a project is not successful, it costs the studios nothing.

Yet, the studios refuse.

There is another shortsighted aspect to relegating mid-budget films to streaming services. Over time the studios have changed consumers’ behavior, inadvertently teaching would-be ticket buyers to stay home unless a movie is a pricey, splashy spectacle. The irony of the studios’ increased over-reliance on nine-figure tentpoles is that they carry tremendous risk. Absent accounting chicanery, no mid-budget movie will ever lose a studio $100M or more by performing below expectations.

It is a vicious cycle of the studios’ own making, where the majority of the theatrically released films must be smash hits, but the reality is not all will be.

The Problem with Peak TV

When we speak of streaming, we often mean television. TV has always been a volume business, but Peak TV, a term describing how there are now many hundreds of scripted shows released in any given year, has rewarded making noise instead of longevity.

The most profitable television shows were always the ones that produced many episodes over the course of many seasons and could then be licensed into syndication, overseas, on home video - or even now to the libraries of streaming services, where they are consistently listed among the most viewed titles on the platform.

By contrast, the standard for a streaming season began at thirteen episodes with Netflix’s first original shows, but it is now ten, eight, even six episodes. Sometimes more than two years pass between seasons. Very few streaming series last longer than four seasons.

The CEOs behind the streamers chose to ignore the very core principle that made television hits profitable, then the legacy studios doubled down when they launched their own streaming platforms and adopted Netflix’s business model.

For the record, there is no data to suggest a streaming service couldn’t produce a network-style, 22-episode season, release it weekly, and find success. But until a streamer does make the attempt, as showrunner John Rogers told me when we developed a project together (that sold to TNT and was killed in the Warner Bros./Discovery merger), “We are all in the miniseries business now.”

The Product Is Now Platforms, Not Films and TV Series

None of this makes business sense unless you consider that, in streaming, the product is not a TV show or a film.

The product is the platform itself.

Until the streamers introduced their ad-supported tiers, even viewership was technically irrelevant, so long as subscribers didn't cancel their subscription. This is called “churn”.

To combat churn, many streamers have now adopted a weekly release pattern. Netflix, meanwhile, releases at least one new series every week, which results in another issue: choice paralysis. This is a marketing term for when a consumer has so many options in front of them, their brains actually stop them from making a decision.

My husband jokes that his favorite television show is the Netflix menu. It’s part of the design. What you watch or how much doesn’t really matter, so long as you find value in still subscribing to the service. It’s no wonder that some of Netflix’s biggest shows — “STRANGER THINGS”, “YOU”, “THE WITCHER” — have recently split new seasons into two parts, released over two different quarters, so the company can tout viewers of those shows as subscribers in both.

Today

Instead of clinging to the past, WGA and SAG-AFTRA members are on strike to ensure both unions’ minimum basic agreements reflect the modern reality of this entertainment industry. One could reasonably argue both strikes are workers’ response to many of the very same challenges detailed in The New York Times article.

Yet the AMPTP has refused to genuinely engage with writers and actors’ core issues:

Wage growth to reflect a high inflationary period

Residuals that restore a semblance of back-end revenue to streaming including performance-based metrics

Rampant free work, whether unpaid rewrites or the increasingly arduous self-taping process

The threat of emerging technologies on employment and compensation

CEOs have not denied that any of these issues affect writers or actors. They have not denied the underlying business model has changed. They simply say it is not a good time to address any of these major concerns.

After all, in 2022, Netflix announced a quarter with a subscriber loss. Suddenly, the economics of streaming turned upside-down. Growth was no longer the only goal. There had to be a plan for profit.

Professor Katz’s chalk dollar sign.

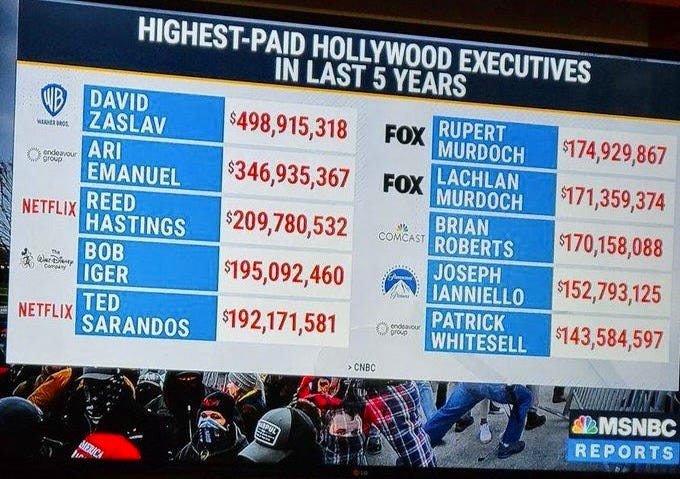

This would all seem reasonable had workers been compensated with a commensurate share of the profits or with higher wages when times were “good”. But looking at figures the WGA has released, in real dollar terms worker pay has actually fallen precipitously:

Median screenwriter pay hasn’t budged since 2018. When accounting for inflation, screen pay has declined 14% in the last five years.

Because workers were not rewarded for their contributions during an industry expansion, it is understandable they have no appetite to take it on the chin during a supposed contraction. That is called exploitation.

In stark contrast, CEO compensation continues to rise. If times truly are no longer “good”, then the pay of each chief executive, whose job it is to set corporate strategy, ought to reflect the downturn into which they led their company. That would be called accountability.

But is it a downturn?

The same CEOs who claim it is not a good time for union workers to demand a fair contract that reflects the new business model are also telling investors the winds are shifting and streaming will be profitable earlier than anticipated. WarnerBros. Discovery has said its streaming business will be profitable in 2023 and both Disney and Paramount Global have promised their investors profitability in 2024 - all during the three-year term of any new collective bargaining agreement the WGA or SAG-AFTRA accept.

According to Disney CEO Bob Iger, striking workers’ expectations are “not realistic”.

Workers, on the other hand, would argue that it is, in fact, the CEOs’ expectations that are “not realistic.”

If Hollywood is suffering, it is not because writers and actors are on strike or demanding a fair contract. It is due to the corporate greed at the heart of the CEOs’ refusal to negotiate based on the reality created by their decisions.

People make choices.

The Jig Is Up

The companies of the AMPTP can afford to pay workers fairly. The CEOs choose not to. As Fran Drescher said on July 13th at SAG-AFTRA’s press conference announcing the actors’ strike: “The jig is up.”

Given recent comments from anonymous studio executives about how there was a collusive agreement between companies in place long before the WGA went on strike, it may be time to look at a different course I took during my junior year: Antitrust and Intellectual Property Law.

Rob Forman is currently running for a seat on the WGAW’s Board of Directors. While 5AM StoryTalk takes no position on candidates in union elections, you can read more about his campaign here.

You can also read more of 5AM Storytalk’s WGA strike coverage here.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, please consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

PSALMS FOR THE END OF THE WORLD is out now from Headline Books, Hachette Australia, and more. You can order it here wherever you are in the world: