Q&A: Screenwriter Eliza Clark on Finding a New Way to Tell Stories

The cancelation of 'Y: The Last Man' after one season hit its creator/showrunner hard, but she found a unique way to get her creative mojo back stronger than ever

Like many people around the world, I spent a large chunk of 2020 in some kind of lockdown. In my case, I was in the U.K. where people were dying at one of the highest rates in the world per capita thanks to the murderous incompetence of its Tory government. On January 6th of the following year, as Donald Trump attempted an insurrection to overturn his election defeat, the U.K. entered yet another lockdown that would last for almost three months. My family moved to Australia a few months later, arriving shortly after the country’s biggest lockdown would begin - meaning I spent some seven months of 2021 in lockdown between the two countries. This might all seem like a lot of extraneous information to share as a way to introduce screenwriter Eliza Clark to you, but I think it’s relevant for you to understand why I wasn’t sure if I was in any state to enjoy her first produced television series as a creator — “Y: The Last Man”, an adaptation of Brian K. Vaughan and Pia Guerra’s comic book series about half the planet’s population dying — when it premiered on September 13th of that year.

Maybe a lot of people felt this way, that they should stay away from something so potentially confronting, but I’m not a lot of people. As it turns out, I needed this wonderful, terrifying, vicarious ride into despair and defiance in the face of such wide-scale death. The good news is, Eliza’s take on “Y: The Last Man” was exactly what I, a fan of the comic, hoped for from it. The cast was spot on, too, led by Ben Schnetzer as Yorick Brown — the last known cisgender male human left alive after everyone else with a Y chromosome mysteriously dies. I was especially pleased by how the adaptation embraced less antiquated ideas of gender, including a new trans male character played by Elliot Fletcher. The ten-episode series wrapped its first season a month later, at which point I looked forward — as I know many others who did — to more seasons that would finish the story I knew so well from print. Alas, that wasn’t meant to be.

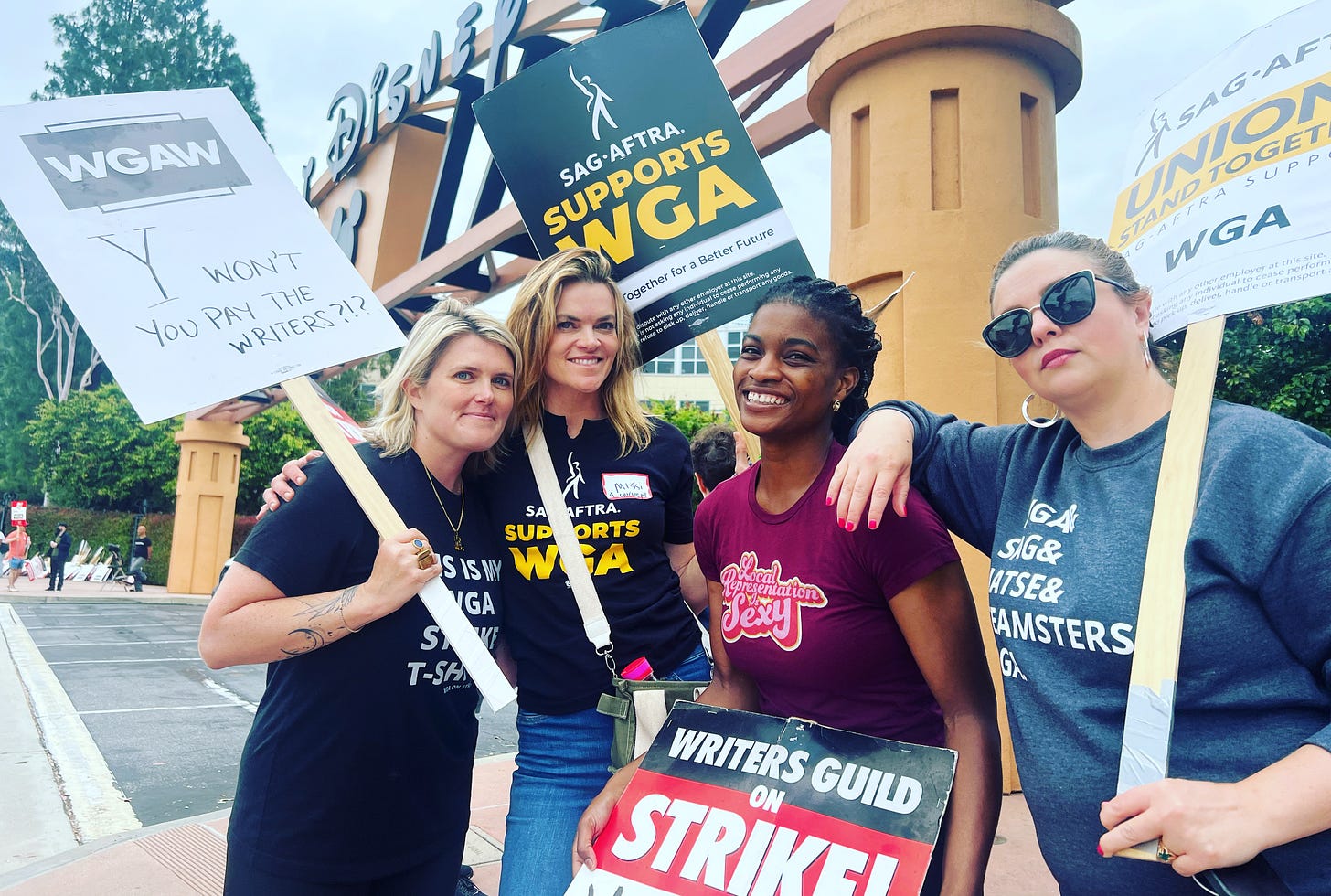

“Y: The Last Man” was abruptly canceled by its network. Eliza (or Eli as she tends to go by) was, by her description, knocked on her ass by the news. She and I will get into this, discussing the similarities and dissimilarities between our one-season series and the emotional and creative fallout that followed them. The significant difference with Eli is that she was a seasoned TV writer by the time this happened to her; she’d written and produced on “Rubicon”, “The Killing”, and “Animal Kingdom” amongst others. Because of this, her perspective was a welcome contrast to my own. The two of us will also get into how she put herself back together afterward. For example, while I distracted myself with home renovations and movie marathons, she may have become…a witch.

Wherever you are on your creative journey, there is a lot to learn here about a unique kind of grief — which is what happens to artists when they lose something they created, that they poured all of themselves into, and how mourning it very often requires a kind of reimagining of one’s self to move forward. Not altogether different than what happens when a loved one dies. Eli and I will talk about much more than that, of course — including her origin as a playwright, craft, and passion for the writers’ room — but I think it’s this part of our artist-on-artist conversation that I’ll carry with me long after I publish it here.

COLE HADDON: Eli, thank you so much for joining me for this conversation. You and I have both had television series on the air for only one season. In my case, I think that’s a good thing and, in yours, I think it’s a travesty. But I’m curious – and I know this probably sounds counterintuitive – but in your mind, did anything good come out of the inexplicable cancelation of “Y: The Last Man”?

ELIZA CLARK: Thank you for saying that about “Y”. I also think it’s a travesty! Honestly, it’s one of the great heartbreaks of my life as silly as that may sound. The cancelation came as a complete surprise to me – which is ridiculous, because I’ve been working in this business for over fifteen years and I should know better. Even so, it completely knocked the wind out of me. I learned a couple of really hard lessons that I think are inevitably good and changed my life for the better. I learned that the future is not promised, and that if I’m going to make art for a living, I need to reframe my idea of success. I’m lucky to be incredibly proud of the work we did on “Y”, I have no regrets, I made lifelong collaborators and friends. Even though they canceled the show, I loved working with FX and would do it again in a heartbeat. We made the show during the worst of Covid in Toronto when every business was shuttered and there were major limitations on filming. We had to shoot an insurrection at the White House with six stunt doubles, which somehow we pulled off. I made the work environment a top priority and I think people liked coming to work, which is ultimately a coup in the midst of a terrifying global pandemic. I’m proud of what we accomplished, and I left it all on the field, I wouldn’t do anything creatively different.

CH: But?

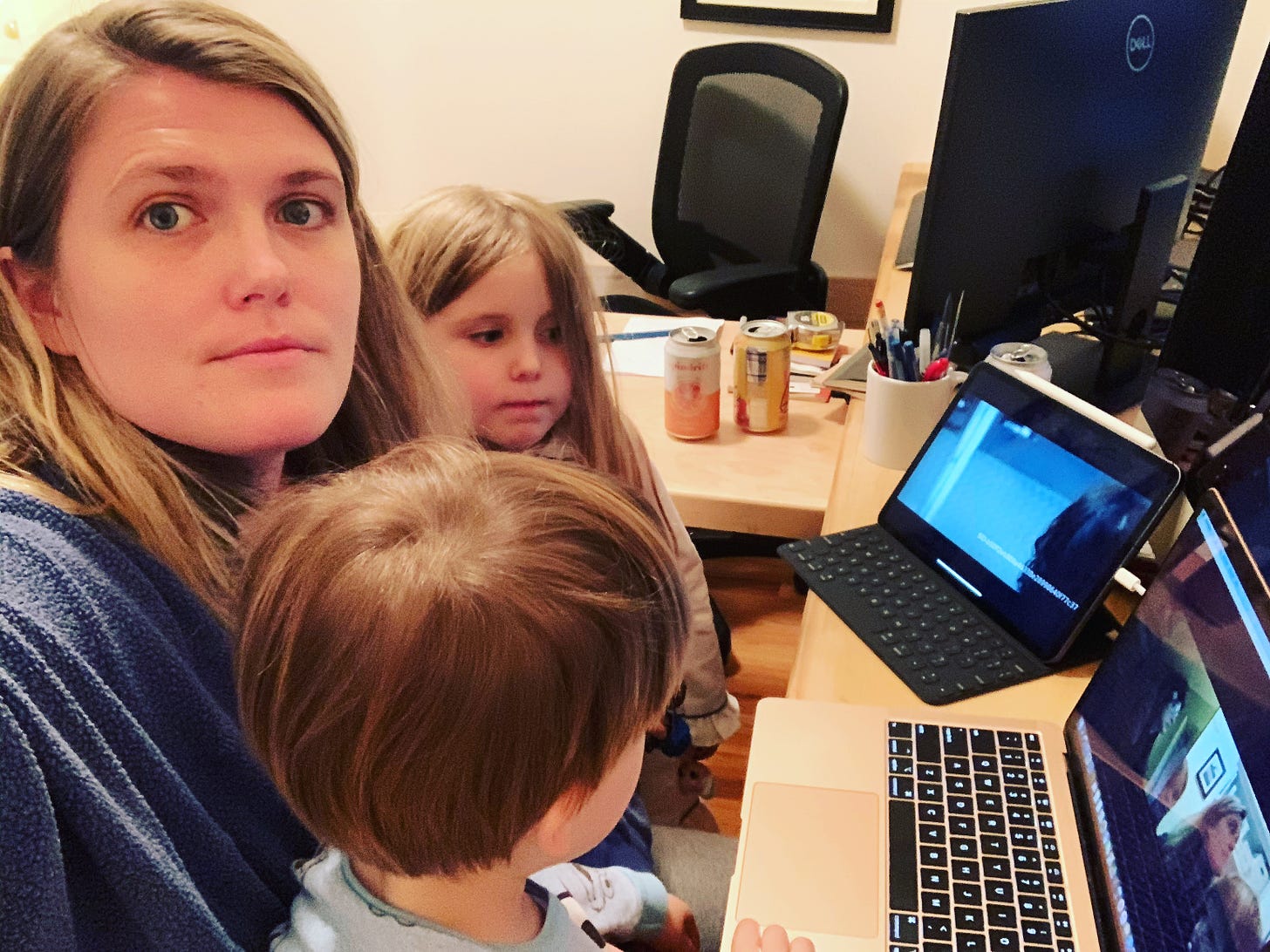

EC: But! One of my regrets from that time is being a workaholic when my kids were little. I kept telling myself that it was just for the first season, just to get the show off the ground, and then I’d bring a little more balance into my life. But ultimately, when you’re a showrunner, there is always work to be done, there will never be a day when you check everything off your list — the list is ongoing. My husband, who is also a writer, was in Toronto with me, far from his family and friends, working a little, but often not working and depressed and held prisoner by me essentially in a foreign country, and I sort of didn’t know how to cope with his depression and my guilt – so I sort of pretended it wasn’t happening. We were all kind of going through the motions, hoping that there would be a life on the other side. Thankfully there was, and my husband, who is my favorite writer in the world, was much happier when he was back in Los Angeles, working and gardening and building things in our backyard – but my big regret is not living my life while it was happening. I was coping with my anxiety about the state of the world by diving headfirst into the work, but it meant that when the show was canceled, it felt like I’d been moving at the speed of light and suddenly hit a brick wall. I had to reintegrate myself into the family. I had to finally pay attention to my husband who’d been really struggling.

CH: Well, shit got real there really quick, didn’t it? [Laughs] I know you’re looking back now, that you’ve had time to process all this, so I’m going to assume you’re okay discussing all this. How did your work respond to the hit you’d taken professional and, it sounds, personally?

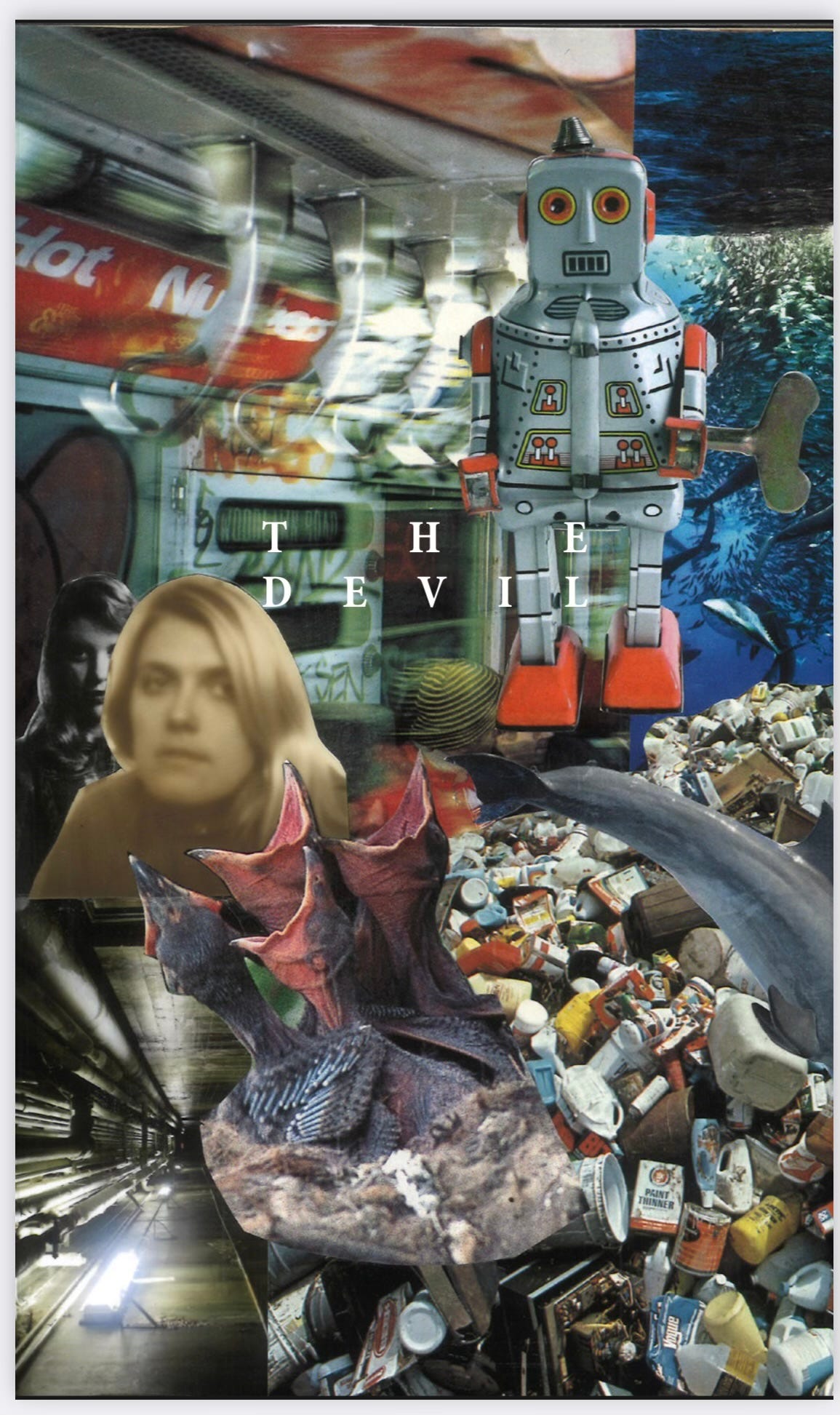

EC: Listen, I’m an oversharer, that’s just who I am. Let’s get into it, you know? It took me a couple of years to get my creative mojo back. I doubted everything that I wrote. I thought “Y” was great, and if that got canceled, maybe I didn’t know anything. I thought I was a person who didn’t let criticism or external validation affect me, but damn was my ego wounded. It was very hard to admit to myself that that’s part of what I was grieving — my ego’s expectations. Every time I would sit down to write, I would be overcome with a crippling amount of imposter syndrome and fear. Ultimately, over the last three years I’ve quit drinking, had a psychedelic-assisted spiritual awakening, learned tarot, created a tarot deck, made thirty-three miniature rooms, started a newsletter, and learned to love writing again. Learning tarot and doing repetitive and tiny little crafts and then working on a writing project – my newsletter – that is not related to “work” completely changed my relationship to making art.

CH: We’re not going to make this about me, but I went through a pretty terrible four-or-so-year stretch that overlapped with the pandemic. Dead parents, international moves, professional upheavals. Not fun stuff, and the consequence was my work really suffered. The joy sort of left it. But like you, I launched a newsletter. About art. And somehow, of all things, this passion project…helped me get my “creative mojo” back, too. Talk about how that worked for you.

EC: First of all, I’m sorry all of that happened to you. That’s intense, and of course your work suffered. We are sensitive creatures, writers! Honestly, the last eight years have been insane for all of us, I think. Stressful and terrifying — global pandemics, millions of people dying, economic recession, insurrections, threats of nuclear war? Remember all the weird nuclear war flirtation that was going on when Trump was president? It was insane. So, I was absolutely in a low point when the show ended and I didn’t know what to do.

I had to do something that was creative but didn’t require my writing brain, which turned into these craft projects — a collage tarot deck, and these miniature rooms I made for my friends. It helped me achieve a creative flow state again, and once my body had felt it and remembered that sensation, I started this newsletter where I was forcing myself to write, but not getting paid for it. It completely worked. I was finally able to get back to loving writing, and after a long strike year, I’m finally working on fulfilling and creative work projects again, but now in a completely new way. I am really enjoying the process, and trying to maintain a level of detachment from the outcome.

But man, yeah, the cancelation of “Y: The Last Man” really knocked me on my ass. I’m curious what you learned from your cancelation? Did it turn you into a tarot witch like it did for me?

CH: [Laughs] I like that – tarot witch – and I’m going to come back to it. As for me, the cancelation of “Dracula” was a reason to celebrate. Without exaggeration, I said, “Well, thank God,” to my wife. We were in a housewares store somewhere in Encino, and a friend texted me about a Deadline article because nobody involved with the production could be bothered to let the creator know.

EC: I’m sorry, but I need to stop and just scream into the void for a second about that. That’s fucked up.

CH: Yes, yes it is. My first thoughts went to the cast and crew, because I knew this would matter to them. But selfishly, it was a relief because I’m not confident I would’ve survived another year of the experience. Afterward, I slipped into depression, or at least that’s what I’ve come to accept I was depressed. It was a very toxic environment, to say the least, and I really struggled to creatively find myself for a couple of years. My agents pushed me toward cashing in on whatever heat I had rather than help me find something I really cared about, which only made matters worse. How did I find my way out of that? What did I take away from it that I’d call positive? The most obvious is the friends I made in the writers’ room, especially Harley Peyton, who has acted as something of a mentor to me over the years. But something else I gained, which I haven’t really discussed before, is how much it taught me I didn’t want to showrun in the U.S. The system just isn’t for me. What I can do outside of America is far better for my mental health and general creative satisfaction.

EC: I’m so curious about that. Tell me more. What is the system like elsewhere? For what it’s worth, I love being a showrunner, and I cannot wait get back to it. I’m dying to get back to it. But it definitely isn’t for everybody! It’s extremely managerial work. You have to be a boss, a money manager, an HR officer, a parent, an artist, a collaborator, and a decision-maker. And probably ten million other things. I thrive in that kind of environment – I love solving production problems, for example. I get excited to fix the script to fit the budget, which is sick that I enjoy that, but I do.

CH: Maybe it’s a little sick.

EC: I’m okay with that. One of the things I’m proudest of is this document I made for my writers called “How to Be a Writer on Set,” because I came up in this business when writers were always on set, and I’ve produced every episode I’ve ever written, even when I was a baby writer, but now so many people have never stepped foot on a set. I like the part of showrunning that is teaching and mentorship. Anyway, I’d love to know more about what it’s like outside of the States.

CH: Well, showrunning is a very new concept abroad, that’s the big difference. Producers do almost all of that managerial work, and they’re very good at it. I don’t want to do that shit. I want to write. Every market is different, of course, but the U.K. is one I work at lot in and can talk a bit more about. Writers tend to instead be commissioned to write every episode, or most of them and partner with only one or two other writers. Smaller season orders make that possible. The time it would take me to write six episodes on my own and develop and refine them with extraordinary producers – which many are – is roughly equivalent to how long I spent in the writers’ room on “Dracula” to break nine other episodes and only write one of those.

Along the way on “Dracula”, I had to contend with a daily barrage of politics that was exhausting and made the experience much more difficult and, overall, devasated the project’s creative integrity. Now, I wasn’t the showrunner. We didn’t have one, only a head writer. But he certainly had no vision for the series except to erase mine. I don’t deal with that nonsense outside of America. When you create a TV show, producers and networks/streamers are investing in your voice, because your vision is paramount. At least from my experience. Then, you – and this is key to why I love it so much – write your scripts in your underwear or sitting at the museum or wherever you feel like, take breaks to go do school runs and meet your friends for coffee or a drink, and nap whenever the need arises.

EC: I have rarely seen it work well when a show has a creator and a showrunner who are two separate people, though occasionally it is great! You really have to have a showrunner who’s invested in mentoring a greener creator and who is helping bring that person’s vision to life. Egos have to be put aside and collaboration has to be front and center. When it does work well, it can be magical, but it’s also potentially explosive. I’m sorry that sucked so much for you. I get what you love about the European model, but I’ve got to say, I love a writer’s room. I love writing alone in my underwear, but man oh man do I like to spend the day with other writers.

CH: Here’s the thing, I do, too. I’ve just learned I like doing it on someone else’s show. Like, if I were in your room, I’d have a blast, I’m sure. I love the submission to someone else’s vision, the surrender of ego that comes with that, the task of helping someone else be brilliant – and, if I’m lucky, be a little brilliant myself. Hopefully. I love the back and forth, the camaraderie, too. But when it’s my own thing, the metrics for enjoyment change and are harder to meet the more people are involved. It’s not impossible and I don’t rule it out at all, but it’s nowhere near as much fun as getting to do that when I’m a cog in someone else’s wheel, if that makes sense.

EC: I totally get that. I think it takes a particular mindset to want to collaborate on your own thing, and also to be able to articulate what it is you like and don’t like in a way that isn’t maddening for the people around you. It certainly takes a lot of discipline, which can be hard to have when you’re that busy. I am a perfectionist when I’m alone. I think that collaborating helps me to unclench my fist on the reins ever so slightly, and ultimately, while my ego likes to think that I know best, I have never been sorry that I let other people make me look good.

CH: I really love that attitude.

CH (cont’d): Okay, so inevitably, I always like to discuss artist’s backstories. Take me back to the metaphorical day when you said to yourself, “Eli, you’re going to be an artist.” What did that mean in your mind as you were starting your creative journey?

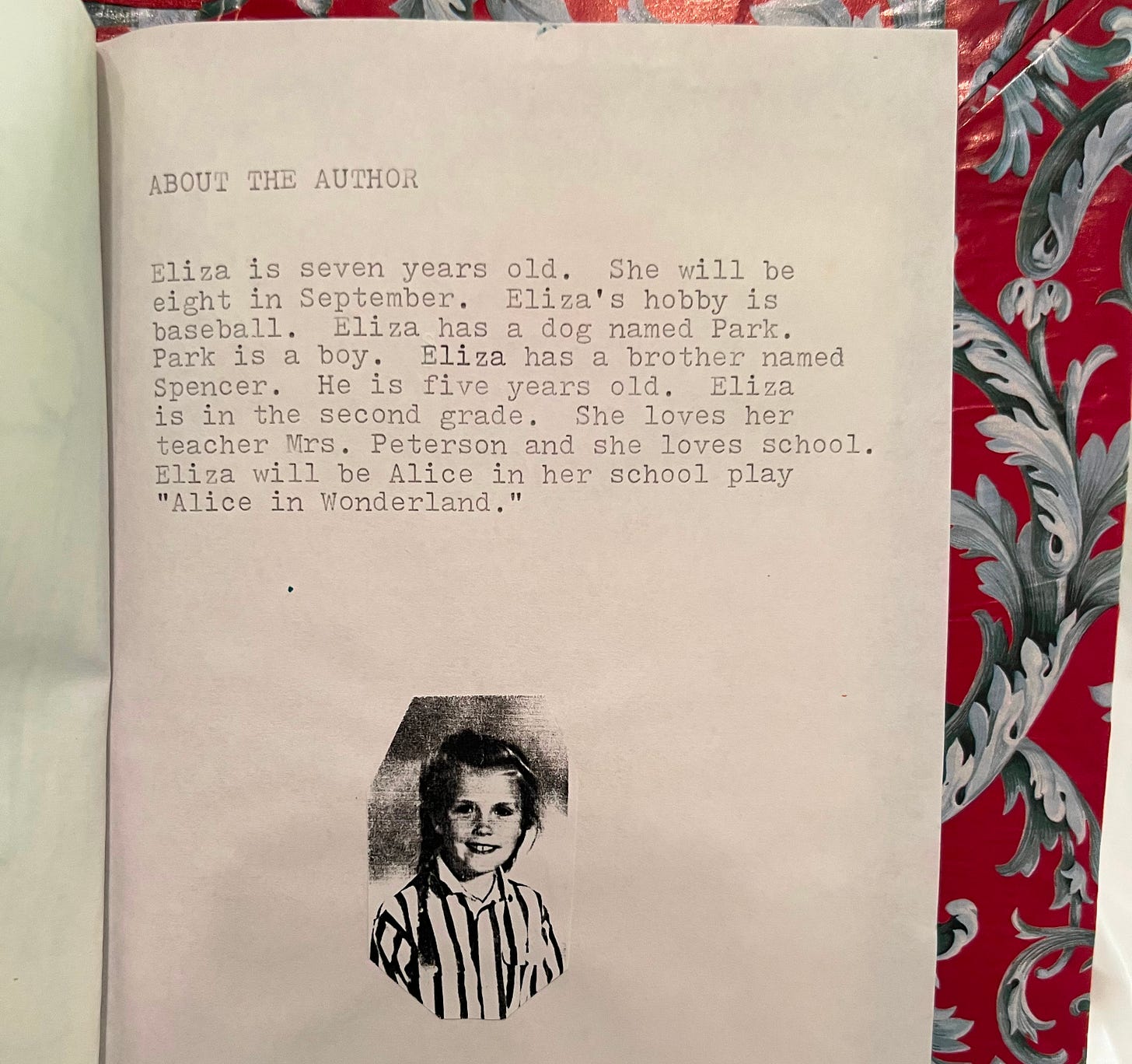

EC: I was a child actor, so I grew up in the business. I did a lot of professional theater — the touring production of Les Miserables and then, later, Broadway, for example. I find a way to sneak that into most conversations, so you really know that you’re dealing with a Broadway actress.

CH: [Laughs] It’s impressive. I understand why you do it.

EC: I was eight.

CH: [Laughs] Okay, but still.

EC: At six years old, I was the lead in an Off-Broadway musical called Opal that was based on a diary of a young girl who had been discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Oregon at the turn of the last century. Anyway, because I am basically Daniel Day-Lewis, I started keeping a diary, too. I’ve got journals from six years old on, which is pretty cool. I was a bossy child with a lot of younger cousins and neighbors who I would force to perform in plays I had “written”. These plays existed mostly in my head, and so it was hard for people to learn their lines, though I definitely expected them too.

My brother is also an actor — he remains a very talented professional actor named Spencer Treat Clark who everyone should hire. Truly, there’s no better actor to work with than a talented actor who also happens to have a writer for a sister.

CH: [Laughs] I’m aware of this connection. He’s quite talented.

EC: Yes, he is! He’s also a lovely person, and he’s word-perfect on the script no matter what. It became clear to me as a teenager that my path would not be acting. My brother is super talented, I was serviceable. I was also a girl, and the pressure on me to look a certain way and be a certain size started very, very young. Like nine. I couldn’t commit to the level of anorexia it would have required for me to continue to be an actress, though I still practiced plenty of disordered eating — child acting is not great for a kid’s ability to trust their body. And just to elaborate on that for a second, I don’t think anyone needs to be anorexic to be an actor, but when I was a child actress in the late nineties, there was literally no way I could be an actor without being under 110 pounds, which just isn’t something my body can do — I’m far too bodacious for that nonsense. Anyway! I knew I wanted to be in the world of creation and make-believe, and I also loved being the person who got to tell the story. I started writing plays in high school — they were bad and self-important, but they got progressively better each time I wrote something new. Eventually, I learned to stop mimicking other writers – Eugene O’Neill, Sam Beckett – and start writing as myself.

CH: Who were you as a writer back then, then?